Commentary: Southeast Asia cannot afford to just lay low until the end of Trump’s presidency

Key US strategy documents indicate that Southeast Asia is not high on the list of priorities, but the region cannot disengage, says Kevin Chen from the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Southeast Asian observers are typically of two minds when it comes to US strategy documents: On one hand, they want to see Washington pay more attention to the Indo-Pacific for security and stability. On the other, they get nervous if there is too much attention on strategic competition with China, especially over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

So when three key documents were released over the past two months – the National Security Strategy (NSS), the National Defense Strategy (NDS) and the Agency Strategic Plan for the State Department (ASP) – observers pored over them, searching for every mention of Southeast Asia to discern how the region and its countries fit in Washington’s world view and priorities.

This time, the strategy documents provided a mixed bag. The documents pointed to a far greater strategic focus in the Western Hemisphere, relegating the Indo-Pacific to second place.

Southeast Asia itself was only mentioned twice in the NSS and omitted entirely from the other papers. While broad mentions were made of Indo-Pacific partners, no Southeast Asian countries were specifically mentioned, nor was the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

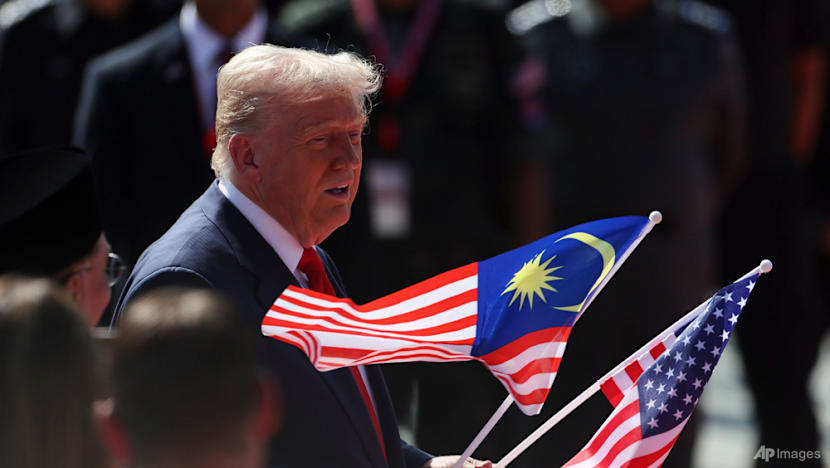

Complicating matters further is the reality of US President Donald Trump’s aggressive foreign policy actions. From his designs on Greenland and Venezuela to his tariff policy, Southeast Asian observers no longer simply worry about abandonment by Washington but whether the US could go from a force for stability to become a disruptor in the region.

Some have even jokingly suggested that Southeast Asian countries may choose to “hide” from Mr Trump’s attention, finding safety in distance.

It is unlikely that these reservations will be resolved by the end of Mr Trump’s term in three years. However, hiding is not a viable long-term strategy. Engagement, if carefully managed, can still yield more benefits than risks.

LOSING CREDIBILITY

During past administrations, discussions about US commitment hinged on issues such as how its engagement was disproportionately focused on defence instead of economics and trade.

Those discussions now seem quaint. The question is not just about how the US engages this region, but whether it will engage at all.

The first credibility issue has to do with US attention to the Indo-Pacific. Granted, though the region was clearly not going to be of greater strategic priority than the Western Hemisphere, it is not as if the Indo-Pacific entirely vanished from the US’ strategic radar either.

As the NDS put it, the Indo-Pacific is critical to prevent China from “effectively [vetoing] Americans’ access to the world’s economic centre of gravity”. Military-to-military ties are also going strong, and though the Philippines was not mentioned in the three documents, over 500 exercises have been scheduled for 2026.

However, there are valid concerns about the ability of the US to focus its resources to more than one region, which would leave precious little capacity to respond to crises elsewhere.

A second issue concerns the credibility of the US approach towards China. The NSS called for Washington to maintain a “genuinely mutually advantageous economic relationship” with Beijing, while the NDS called for a “decent peace, on terms favourable to Americans but that China can also accept and live under”.

What these terms will look like in practice remains to be seen, but the risks cannot be ignored.

What countries in Southeast Asia fear is not a US-China rapprochement per se, but a G2 arrangement in which Washington and Beijing behave as the only actors with sovereignty and agency. If ASEAN is sidelined in decisions affecting the region, this would be a body blow for ASEAN centrality.

THE TRUMP FACTOR

Yet the biggest issue hurting the US’ image in the region is also the most intractable: Mr Trump’s actions.

He is much harsher on allies and partners than on adversaries, using tools such as tariffs to achieve his goals. Washington may see this as calling in favours from countries that have benefitted from the US-led order, but not everyone agrees.

Notably, Mr Trump’s intent to pursue America’s security goals in the Western Hemisphere is already rattling leaders in Southeast Asia.

They have expressed concerns about Operation Absolute Resolve in Venezuela, warning that it sets a “dangerous precedent” over the use of force and undermines the broader international system. The standoff over Greenland also drew remarks about how no country should be allowed to “conquer” a sovereign state.

Any promise from the US, whether to uphold international law or criticise China for impinging on another country’s sovereignty, rings hollow amid these developments on the other side of the world. Southeast Asia has worked with strongman leaders before, but leaders that disrupt the rules-based order under which they prospered are a separate concern.

ENGAGING WASHINGTON WITHOUT INCURRING ITS WRATH

Despite the temptation to distance one’s country from the US and hide, this is not a viable long-term strategy to dealing with Mr Trump. The region still counts the US as an important economic and security partner.

Southeast Asian countries should continue to engage Washington, if only to ensure that their institutional links remain strong. In fact, the NSS’ call to engage governments with “different outlooks” opens the door for mending ties with countries it used to overlook.

Cambodia is a case in point. Admiral Samuel Paparo, the head of US Indo-Pacific Command, visited Ream Naval Base in January. With the base long accused of being an outpost China’s Navy, his visit to the base suggests a willingness to move past this thorn in the US-Cambodia relationship. The US and Cambodia are also scheduled to resume the dormant Angkor Sentinel military exercise in 2026, opening the door for even deeper engagement.

It will take careful planning to engage Washington without incurring its wrath. But for the moment, the benefits of engagement still outweigh the cost of hiding.

The US strategy documents may not have given this region the clear commitment that it sought, but leaders here can strive to calibrate their own responses to this challenging time.

Kevin Chen is an Associate Research Fellow with the US Programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. He writes a monthly column for CNA, published every first Friday.