commentary Commentary

Commentary: 2021 has already seen the wettest and driest months in decades. Is Singapore prepared for more?

Singapore must brace itself for adverse climate impacts such as extreme rainfall and drought, say Dhrubajyoti Samanta and Benjamin P Horton.

People walk with umbrellas under the hot sun in Singapore. (Photo: Ooi Boon Keong/TODAY)

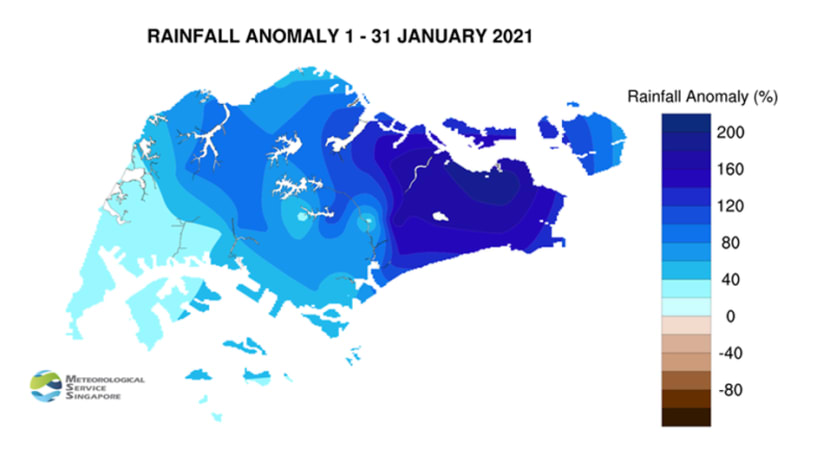

SINGAPORE: The rainfall over Singapore in January was exceptional due to strong northeast monsoons during the first 14 days of 2021.

The Meteorological Service Singapore (MSS) report stated it was the wettest January in the last 40 years. The maximum positive rainfall anomaly of 194 percent was observed over the eastern part of Singapore.

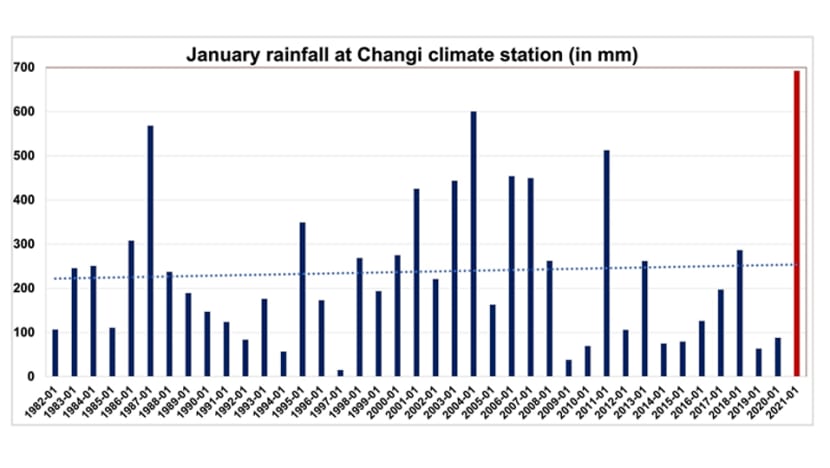

The rainfall record at Changi climate station started in 1869. January 2021 was the second wettest January ever at Changi climate station with 693mm rainfall (January 1893 was first with 819mm of total rainfall).

Interestingly, out of a total of 693mm rainfall, Changi climate station experienced 649mm rainfall in just the first 14 days of January.

READ: Commentary: Not quite winter in Singapore, but no shame in bringing out the sweaters and jackets

The rainfall data reveals an increasing trend (0.4mm per decade) at Changi climate station since 1982. This long-term monthly and annual rainfall increase is a clear indication of climate change.

Climate scientists expect that as global temperatures rise, much more rain will fall in extreme downpours. The warmer the atmosphere, the more moisture it can hold, which means rainfall will be greater and more intense.

However, more research is needed to quantify the rainfall changes in Singapore, since Singapore also experiences rainfall variations arising from the natural variability.

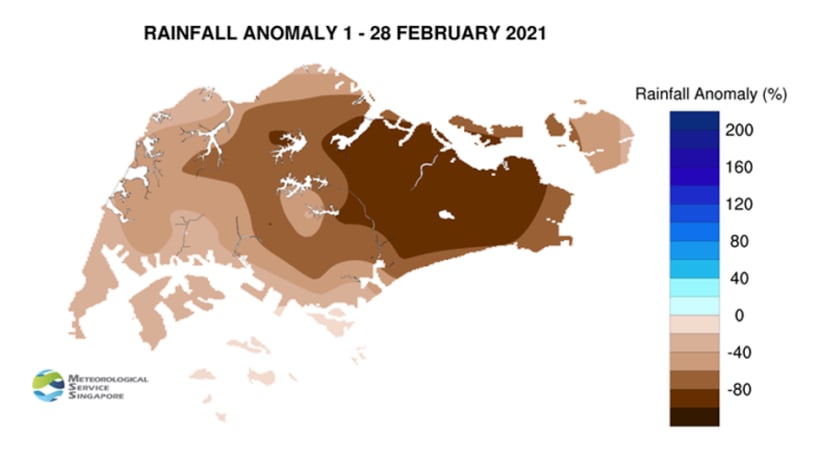

After an unprecedentedly wet January, Singapore then experienced the second driest February on record after 2014. Changi climate station recorded only 1mm of rainfall during the entire February.

This dry weather was also associated with the record lowest average daily relative humidity (73.8 per cent) in February since measurement began in 1984, possibly due to less availability of water vapor content and negligible rainfall over Singapore.

READ: More rain expected in first half of March, possible highs of 34 degrees Celsius

ROLE OF NORTHEAST MONSOON SURGES AND LA NINA IN JANUARY

Occasional strengthening of north-easterly winds due to an increase in high-pressure systems over northern continental Asia is a typical characteristic of the northeast monsoon (December to March).

Such strong northeast winds, coupled with wind convergence, produce strong gusts and heavy rainfall over Singapore and the surrounding region.

Two such surges occurred over the equatorial South China Sea region from Jan 1 to 2, and Jan 8 to 13. These surges brought widespread continuous rain, which was heavier over specific areas in Singapore.

READ: Commentary: A decade of climate change has had devastating impact. But there’s hope yet

While these resulted in a temporary drop in temperature, Singapore experienced several flooding events during the first fortnight of January. Heavy rainfall led to high water levels at Rochor Canal, Bishan Ang Mo-Kio Park, Kallang Basin and many other places.

The higher rainfall in January 2021 over Singapore may also have resulted from La Nina-induced convection over Southeast Asia.

La Nina is a weather pattern that naturally occurs every 2 to 8 years because of variations in ocean temperatures in the equatorial band of the Pacific Ocean. It arises as strong winds blow warm water at the ocean's surface away from South America, across the equatorial Pacific Ocean towards Southeast Asia, leading to enhanced convection and rainfall over the region.

READ: Commentary: Living in the tropics under climate change will be challenging

DRIER CONDITIONS IN FEBRUARY

Historically, February is the driest month of the year in Singapore. February’s long-term (1982 to 2020) mean rainfall (105mm) is even lower than the hottest months of May (166mm) and June (134mm).

In February, the rain belts get narrower or move southward to Java. Consequently, cold surges become northerly and cross the equator near Karimata Strait.

The change in rain belts breeds dry conditions in Singapore and wet conditions near Java. But what exactly made February 2021 the second driest February in Singapore’s history is unknown and an avenue for further research.

For instance, the dry spell this February may have been caused by lower moisture availability and significantly weaker convection related to the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO).

The MJO provides a significant portion of the rainfall in Singapore. It is an eastward moving disturbance of clouds, rainfall, winds and pressure that travels through the global tropics and returns to its initial point in 30 to 60 days.

ROLE OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Long-term observations in Singapore reveal a significantly increasing trend in rainfall and temperature. Indeed after record rainy days in the summer monsoon of June to September 2020, heavy rainfall this January is yet another alarming data point.

READ: Commentary: Why that unusually high rainfall in Singapore during the last summer monsoon may be our new normal

While further research is needed to find the direct linkages of climate change with unusual weather this year, we must prepare for more extreme scenarios in Singapore.

Along with rising sea levels, Singapore’s drainage system may face further challenges if heavy rainfall becomes more frequent in the future.

READ: Commentary: How prepared is Singapore for the next flash flood?

We must also prepare ourselves for the consequences of severe and frequent dry conditions in Singapore. For instance, dry spells could affect our reservoirs’ collection of water and local farming processes, which could have an adverse impact on Singapore’s efforts for food and water security.

More attention on rainwater storage for dry conditions will be useful in the coming decades.

Enhanced monsoon surges could also bring more anthropogenic pollutants from East Asia to Southeast Asia via stronger north-easterly winds. The potential threat to air quality (such as an increase in carbon monoxide) could pose public health risks, and thus needs more monitoring and research.

Listen to Dr Benjamin Horton explain how climate change is transforming our oceans, leading to bigger storms and weather extremes.

Dr Dhrubajyoti Samanta is a Senior Research Fellow at The Asian School of the Environment at Nanyang Technological University (NTU). Professor Benjamin P Horton is the Director of NTU’s Earth Observatory of Singapore.