China built houses fast for decades. Why is 'good housing' now the new priority?

As China pursues a rethink of its housing policy, analysts warn that entrenched practices and misaligned incentives could undermine the push.

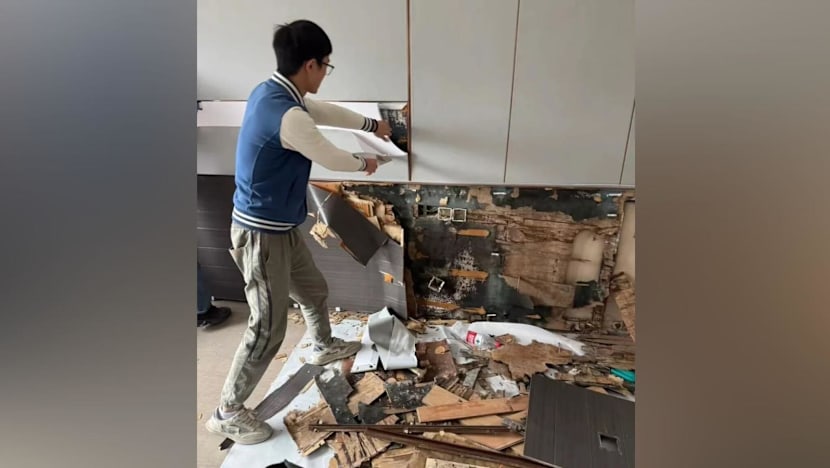

Mould and water damage were uncovered behind a bedroom wall during an inspection of a newly built apartment in Shanghai, China. (Photo: Xiaohongshu/长腿乐乐侠)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SHENZHEN: Preparing to move into his new family home in Shanghai’s Baoshan district last September, Liu Jun (not his real name) thought the hardest part of adulthood was behind him.

The apartment, which cost nearly 8 million yuan (US$1.1 million), was the biggest purchase of his life, one that his parents helped finance.

He and his girlfriend had planned to move in before Chinese New Year, introduce the flat to their parents and begin life together under their own roof. The couple had hoped to use the new flat to host both families ahead of a planned wedding this year.

But instead of a new beginning, it became what the 27-year-old securities company employee described as a nightmare.

They paid around 300 yuan for a pre-handover inspection meant to offer reassurance.

Instead, the checks unearthed serious problems that brought those plans to an abrupt halt.

“We had already flagged water seepage issues and excessive moisture levels in the master bedroom wall,” Liu, who asked not to be identified as he is pursuing legal action, told CNA.

“But the more we tore things apart, the worse it got. We eventually discovered that the entire exterior wall was leaking. Once it was opened up, there was mould everywhere, and even insects growing inside the backing panels,” he said.

“How did they have the cheek to hand over a house like this?”

Stories like Liu’s are not isolated as China’s property sector shifts from years of breakneck construction to a reckoning over what was built, and the quality.

Defects, delivery disputes and quality failures have increasingly surfaced as the sector slows and buyer confidence frays.

Tackling these issues now sits at the heart of a broader policy push towards “good housing”, or “hao fang zi” in Chinese, that aims to move the sector away from speed and scale towards safety, liveability and long-term use - while also shoring it up.

New national rules raise minimum floor heights, impose stricter limits on noise between units, and expand lift and accessibility requirements.

“This strategic pivot to ‘good housing’ is fundamentally about rebalancing the economy - shifting from speculative inventory to quality living,” Lin Han-Shen, China country director at The Asia Group, told CNA.

“Restoring household confidence is central. When buyers no longer fear construction halts, some latent demand could unlock,” Lin said, referring to households that had delayed purchases amid delivery risks, returning selectively once confidence improves.

At the same time, analysts warn that translating this emphasis into lasting improvements will be difficult: Entrenched practices run deep, and correcting workflows and mindsets shaped by years of rapid construction will be far harder than setting new standards on paper.

QUALITY OVER QUANTITY

Officials have defined “good housing” as one that is safe, comfortable, green and smart, with higher baseline standards covering features such as ceiling height, ventilation, natural light, sound insulation and indoor air quality.

While the term first emerged in August 2022, it only gained policy prominence last year when it was written into the government work report at the Two Sessions political gatherings in March.

It was subsequently referenced at a key party conclave in late October, when Communist Party leaders outlined priorities of the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026 to 2030), and again during the agenda-setting Central Economic Work Conference last December.

In official language, the emphasis signals a move away from volume-driven construction towards standards centred on build quality, liveability and durability.

The policy push comes as evidence points to widespread quality problems across new homes.

A nationwide review by Zhijian Cloud, a construction quality data platform, based on third-party inspections of more than 100,000 newly completed homes found that nearly two-thirds of units delivered in 2025 were rated “poor quality”, roughly six times the share in 2022.

Assessments of the subpar units typically cited problems such as wall cracking and hollowing, water leakage, poorly installed doors and windows, flooring defects and failures in concealed systems such as wiring and drainage.

Such issues were evident in Liu’s case. More than three months after the contractually agreed delivery date, his apartment has yet to be formally handed over.

According to him, the developer, a subsidiary of a large state-owned property group, has changed the access password, leaving Liu locked out even as construction workers continue repairs. Meanwhile, he is servicing a monthly mortgage of nearly 20,000 yuan on a home he cannot live in.

Chen Bin, chief executive of home inspection firm Originality of Home Inspection, which operates in cities including Beijing, Shenzhen and Hangzhou, said defects in waterproofing and concealed systems are widespread in many newer projects, often linked to cost pressures, layered subcontracting and rushed finishing.

During an inspection observed by CNA in early January, a home inspector at Chen’s firm said hollowing in walls and floors was among the most common defects, alongside loose door frames, unstable cabinets and poorly secured fittings.

“Almost every home has some problems like these,” he said, adding that such defects are difficult to avoid in large-scale developments.

Earlier that day, he inspected an apartment measuring more than 100 sq m and flagged over 100 separate issues, ranging from hollow tiles to missing fittings.

“We’ve found apartments where sockets were cut open but never installed, with exposed wiring, and even lights coming loose.”

Analysts said these issues reflect a deeper governance gap, where years of speed-driven development left housing quality treated as a one-off construction issue rather than something managed across a home’s life cycle.

Xi Guangliang, a research fellow at Nanjing University’s School of Architecture and Urban Planning, said many of these problems are not new but were long obscured by years of rapid expansion.

“In the past, the industry placed far more weight on speed and scale. Housing quality control and long-term operations were structurally undervalued,” he told CNA.

As margins came under pressure, quality was often the first casualty, said Tian Kun, a senior lecturer in marketing and analytics at the University of Kent.

“Much of the existing stock prioritised speed, scale, and floor area over liveability, energy efficiency, and long-term usability,” Tian said, adding that this left buyers increasingly dissatisfied as expectations shifted.

Analysts said policymakers are increasingly viewing China’s property problem as one of confidence and transition rather than a cyclical slowdown that can be fixed with short-term stimulus.

After years of falling sales, prices and developer distress, China’s property sector is now being steered away from stimulus-led recovery towards stabilisation.

Recent measures, including urban renewal, inventory management and the “good housing” policy, reflect a push to emphasise build quality, delivery and long-term use over rapid expansion.

That shift is already visible on the ground, said Pan Wanxia, general manager for Tianhe district at Guangdong Centaline Property Agency.

Buyers today are no longer focused on a single factor such as location or price, she said, but instead weigh housing quality, layout, estate management and long-term liveability as a package.

“Most urban households already have a place to live,” Pan told CNA. “When they upgrade, they are looking for a clear improvement over what they already have, not just another unit.”

RENTALS UNDER SCRUTINY

Quality concerns are not confined to owner-occupied homes.

Analysts said many of the same incentives that fuelled rushed construction in the sales market are also distorting China’s rental sector, where speed and short-term returns often outweigh safety and durability.

A 2025 industry paper estimated China’s rental population at nearly 260 million, underscoring the scale of the market in a country of 1.4 billion people.

One flashpoint has been quick-flip rental flats, known as “chuan chuan fang” in Chinese, a term borrowed from Chongqing slang for intermediaries, now used to describe homes rapidly renovated and re-rented for short-term gain.

Media investigations and court cases have linked some of these units to excessive formaldehyde levels, which often only surface after tenants move in due to rapid, low-cost renovations with little time for ventilation.

“At a structural level, issues like chuan chuan fang stem from a combination of tight rental supply in major cities, weak regulation of small landlords, and incentives to maximise short-term rental yields through rapid subdivision and low-quality renovations,” said Tian from the University of Kent

NJU’s Xi said quality oversight in China has historically focused on new-home delivery, while secondary renovations and short-cycle rentals remain weakly regulated.

“If ‘good housing’ is to rebuild trust, it has to extend beyond new-home delivery to cover renovation, rental use and long-term management,” he said.

Analysts noted that quality risks are notably widespread in older walk-up apartments, or “lao po xiao” in Chinese, where ageing infrastructure and ad-hoc renovations pose growing safety concerns.

Policymakers have also linked the “good housing” push to urban renewal, including the upgrading of older residential blocks, extending the quality drive beyond new-home delivery.

In response, some cities have begun piloting rules that extend minimum safety and environmental standards to refurbished homes, signalling that the “good housing” push is starting to reach existing stock.

HOW DOES “GOOD HOUSING” HELP?

But what does “good housing” mean in practice?

For buyers, this means fewer hidden defects, clearer baseline expectations and stronger grounds to challenge substandard delivery.

“Today, public demand for housing has shifted from basic access to quality living,” housing minister Ni Hong said at a State Council Information Office press conference in October 2024, adding that demographic changes and evolving lifestyles were making housing needs more personalised and diversified.

Beyond design standards, the push places greater emphasis on better construction materials, tighter quality control during the building process and utilising technology to improve energy efficiency and liveability throughout a home’s life cycle.

“Violations of quality standards could accelerate consolidation under a less sympathetic government, especially in cities with stronger enforcement capacity,” said Lin from The Asia Group, adding that enforcement would need to be balanced against job losses, particularly in lower-tier cities.

But analysts said the significance of the shift lies less in individual technical standards than in how they reshape incentives across the property sector.

“The quality housing focus signals a shift in the incentive structure: By tying future project approvals and financing to quality benchmarks, it forces a sectoral ‘survival of the fittest’,” said Lin from The Asia Group.

In practice, analysts said this could gradually reshape how developers are evaluated, placing greater weight on delivery records, construction quality and compliance rather than scale alone.

Raising standards, however, also comes with trade-offs.

“As standards rise, so will costs in the form of better materials, smarter design, green certification,” Lin said.

“The key question is allocation. Are buyers willing to pay a premium for certified quality? Will developers accept lower margins? Can local authorities offer incentives such as faster approvals?

“The real test is whether Beijing can break the local implementation gap, where growth pressures often dilute standards,” Lin said.

Tian from the University of Kent said the effectiveness of the policy push ultimately depends on whether standards are applied consistently throughout a project’s life cycle, from approval and construction to delivery and property management.

Without that, he warned, higher standards risk becoming box-ticking exercises rather than lasting improvements in liveability.

WILL THE CRISIS BOTTOM OUT?

Analysts said the push for “good housing” is unlikely to end China’s property downturn on its own, but may help stabilise expectations and restore trust in top-tier cities over time.

Tian said China’s housing market is entering a phase more typical of mature Asian economies, where most urban households already own homes and demand is increasingly driven by upgrades rather than first-time purchases.

A 2019 survey by the People’s Bank of China found that 96 per cent of urban households in China owned their homes, far higher than in many advanced economies.

“In such an environment, simply building more units or loosening credit is unlikely to generate sustainable demand,” Tian said.

Emphasising higher standards is also intended to “rebuild confidence in homeownership as a stable store of value rather than a speculative asset”, said Zhang Yuhan, principal economist at the Conference Board’s China Centre, a global nonprofit think tank.

Zhang said the shift towards higher-quality housing is “likely to support confidence gradually”, but cautioned it does not resolve oversupply or developer liquidity pressures on its own.

Lin from The Asia Group described it as a “long-term recalibration” of what the property sector should do - serving actual housing needs rather than financial speculation.

“Think of this housing policy as surgery on the (property) sector’s future, not a drug to alleviate pain for its past,” said Lin.

By 2026, he said, a clearer bottom in prices and sales activity could emerge in tier one and core tier two cities, particularly where completion rates improve and upgrade demand is released, even as the broader national market remains uneven.

“It’s less a V-shaped rebound than a gradual, two-tiered healing process,” Lin said.

“We may see a clearer bifurcation - a premium, quality-driven segment recovering, while the broader sector remains in consolidation.”

For Liu, the Shanghai homebuyer still waiting to take possession of his flat, the policy debate ultimately comes down to something far more basic.

“When you buy a phone or a television, there are return policies and consumer protections,” he said.

“But when it comes to buying a home, even the most basic standards aren’t guaranteed.”

After months of delays, inspections and complaints, Liu says his expectations have narrowed to one simple demand.

“A house should at least be a place that keeps people safe from wind and rain.”