IN FOCUS: What's low-altitude economy, and is China struggling to make it fly?

China is on a policy-fuelled push to turn the likes of drones and flying taxis into everyday business. Patchy progress and lagging rules risk grounding its sky-high ambitions.

China is on a policy-fuelled push to turn drones and air taxis into everyday business. But headwinds lie in the way of its sky-high ambitions. (Illustration: CNA/Rafa Estrada)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SHENZHEN: On a humid afternoon at Shenzhen’s Yanzi Lake International Convention Centre, the future of flight looks less like a sleek jet and more like a folded scooter.

Homegrown start-up Hope Loong is showing off its prototype “flying motorbike”, a three-wheeled craft with rotors tucked away, designed to roll through a carpark as easily as it might hop over traffic for a few minutes in the air.

“We first make the product good,” said the firm’s chief executive Pan Dewu. “Regulators will follow the maturity of our product. We’ll keep testing, collecting safety data and giving them to the authorities.”

It’s a small but telling piece of China’s burgeoning low-altitude economy - a policy-fuelled race to turn drones, flying taxis and other flights skimming the skies into everyday business.

The potential upsides are hard to miss: unclogging roads, cutting delivery times and powering new services in everything from tourism to healthcare.

Yet Beijing’s sky-high ambitions to harness what it has branded a new growth engine are outpacing the rulebook. Even as innovation races forward, authorities are moving cautiously and placing safety before speed.

Nearly two years into the push, results have also been uneven. While dozens of pilot zones have taken off, few have achieved real commercial lift.

Analysts say China’s low-altitude push sits at the crossroads of ambition and caution - a test of how fast the world’s second-largest economy can turn its vision into viable industries.

Emerson Xu, CEO of Singapore-based advanced air mobility consultancy NexAvian, said Chinese manufacturers are still learning to balance cost control with stringent safety standards.

“The West had a century-long head start - learning through flying, failing and improving - while China is trying to compress that learning curve within years,” he told CNA.

“But with its national focus and engineering ingenuity, I believe China will eventually catch up, and even overtake, as it builds on those global lessons.”

SKY-HIGH AMBITIONS

But what exactly is the low-altitude economy?

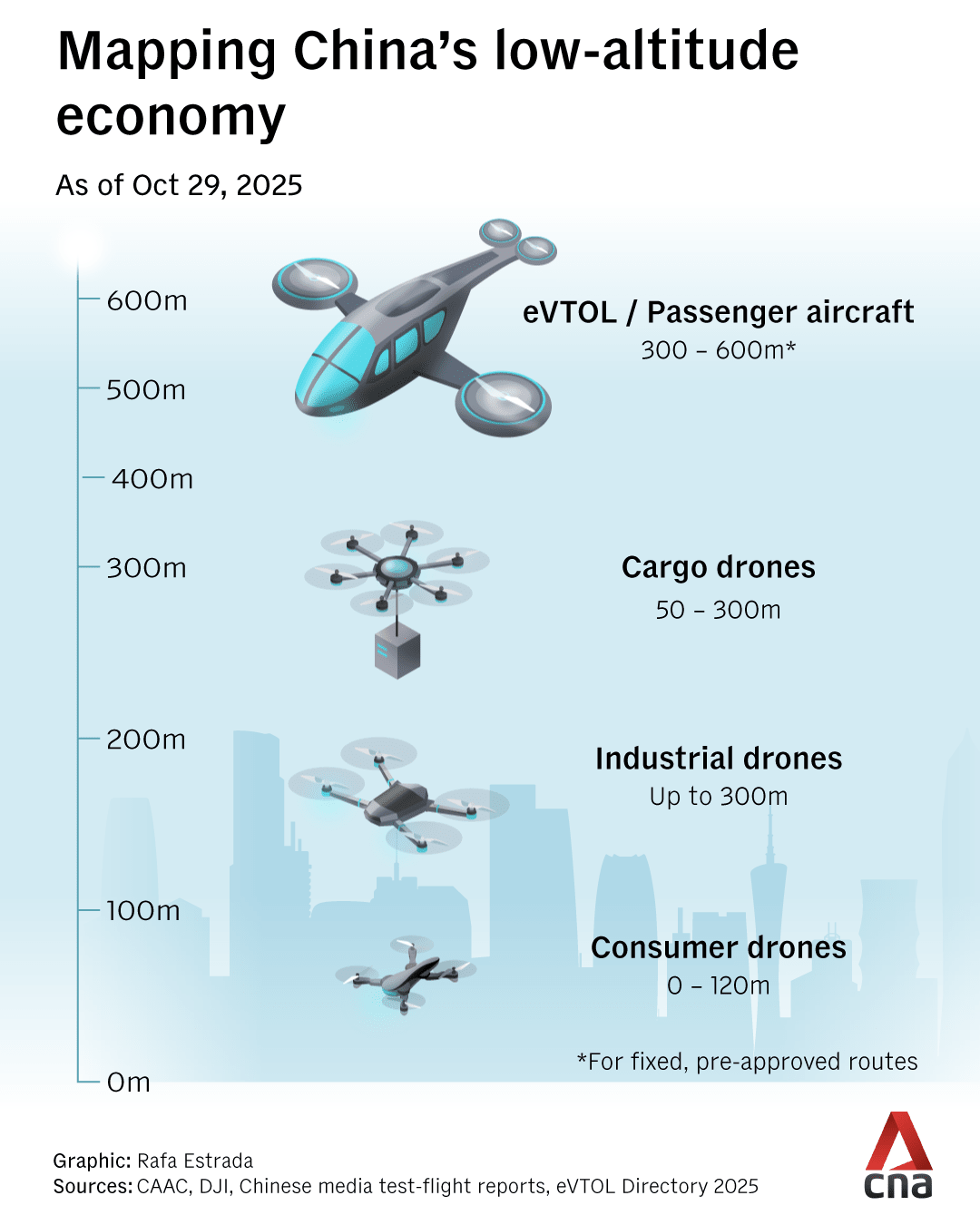

Simply put, it’s a catch-all term for commercial activity in airspace generally below 1,000m - extendable up to 3,000m - spanning everything from delivery drones and sightseeing flights to crop-spraying, cargo runs and even disaster relief.

China has made the sector a national priority.

For the first time, it was written into the Government Work Report in March 2024, where Beijing pledged to foster “new growth engines” in the skies alongside artificial intelligence (AI) and other “future industries”.

That commitment was reinforced in the 15th Five-Year Plan - China’s development blueprint for the rest of the decade - which was recently endorsed at a key political gathering.

The plan names the low-altitude economy, or “dikong jingji” in Chinese, as a strategic industry alongside others such as aerospace and new energy, Beijing’s umbrella term for renewables and clean power.

The Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) projects that the low-altitude economy will reach 1.5 trillion yuan (US$210 billion) by the end of this year and 3.5 trillion yuan by 2035.

Thirty regions have already included the industry in their work plans, covering most of the country.

Guangdong province has emerged as a key launchpad thanks to its strong industrial base, regional coordination and early policy push. The southern manufacturing powerhouse alone claims more than 15,000 firms related to the low-altitude economy, accounting for nearly one-third of the national total.

Three core cities - provincial capital Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Zhuhai - drive growth, supported by surrounding hubs like Foshan, Dongguan and Huizhou.

Guangzhou, home to homegrown industry leader EHang, hosts China’s first passenger eVTOL (electric vertical take-off and landing) aircraft certified for commercial use, running short sightseeing flights under regulator supervision.

In tech hub Shenzhen, authorities have moved from talk to take-off. The city plans over 1,000 flight routes and 1,200 take-off sites by 2026, with nearly three-quarters of its airspace below 120m already open.

That openness makes it China’s most active pilot zone, ahead of Shanghai and Chengdu, with flight corridors cutting across industrial parks, tourist areas and coastal routes.

Ambition is matched by incentives. Earlier this month, Shenzhen rolled out one of China’s most generous policies yet - offering a 15 million yuan reward for every certified passenger eVTOL, while also rewarding drone operators by flight volume and new routes.

The city also boasts facilities such as Shensi Lab. The first of its kind in China, it helps firms test aircraft under simulated wind and heat-island conditions to strengthen safety data for future approvals.

To the west, Zhuhai has launched trial helicopter air-taxi routes linking cities across the Greater Bay Area - the southern economic cluster comprising Hong Kong, Macau and nine cities in Guangdong - cutting intercity trips from three hours by road to about 30 minutes.

Elsewhere, cities such as Hefei, Tianjin and Chengdu are developing dedicated pilot projects focused on manufacturing, certification and public flight testing in the low-altitude sector.

China is also grooming talent for lift-off.

In August, the Education Ministry received applications from 120 universities to offer “low-altitude technology and engineering” programmes, following the approval of 23 institutions last year.

The first cohort began in September last year at institutions such as Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Anhui University in Hefei, focusing on flight control, air traffic management, and network systems for future low-altitude operations.

Industry watchers say the pace of progress reflects both genuine traction and policy heat.

“It’s about … 60 per cent genuine commercial traction, 40 per cent policy push,” said Kenneth Goh, director of private wealth management at UOB Kay Hian.

He warned that policy enthusiasm carries risks, pointing to the electric vehicle and solar power sectors where early success led to “over-investment and duplication”.

“When Beijing calls something a ‘new growth engine’, local governments rush to build clusters, often duplicating capacity,” he told CNA.

“The technology is mature and commercial applications are profitable. But infrastructure investment shows policy-induced heat. This is a 2030–2035 structural theme, not a short-term bet.”

HITTING TURBULENCE

Yet for all the momentum, China’s low-altitude flight path is clouded by headwinds.

Chief among them are regulations, with the rulebook still lagging behind the pace of innovation, highlighted analysts and industry players.

Existing rules for unmanned aircraft flights cover only drones used in logistics, filming and inspection.

Passenger and heavy-cargo eVTOLs instead fall under the CAAC, which requires full airworthiness and operator certification - a process companies say can take years.

“The legal framework is still catching up,” Helen Wong, a China investment and corporate lawyer, told CNA.

Oversight, she noted, is split among the military, civil aviation and local governments. Temporary flight approvals can take up to two weeks, and inconsistent enforcement has created what she called a “one province, one policy” patchwork.

China is revising its Civil Aviation Law for the first time in 30 years, adding new rules to support the fast-growing low-altitude economy.

A draft in June 2025 called for unified supervision, smarter airspace management and stricter safety standards, though no timeline has been set for the amendments to take effect.

Key pillars include optimising low-altitude airspace allocation, building a national flight-management and airworthiness system for drones and eVTOLs and encouraging innovation in aircraft manufacturing and infrastructure to support safe, scalable operations.

“You can’t just think about flying vehicles or flight regulations,” EHang’s He said. “You have to consider how they integrate with ground traffic, rail systems and even pedestrian movement.”

Those considerations are particularly relevant to Hope Loong’s “flying motorbike”, which CEO Pan has portrayed as more of a hybrid craft - at least for now.

“Be realistic, flight maturity isn’t there yet. You won’t use it as a constant air transport. Today it’s for short hops, an emergency, a jam, a few minutes across town. When it’s not in the air, it should be a ground vehicle,” he said.

Technology adds another layer of turbulence to China’s low-altitude dreams, according to analysts and a government-affiliated research institute.

While the country leads in consumer drones, passenger-grade eVTOLs still rely on imported chips, sensors and flight-control systems - a dependency that has slowed certification and raised costs, industry executives said.

A 2025 report on the low-altitude economy by the state-backed China Electronics Information Industry Development Research Institute lists endurance and core-technology bottlenecks as key obstacles to scaling up.

Yet the ultimate checkpoint is safety, with regulators insisting it must clear the runway before the low-altitude industry can truly take off.

The National Development and Reform Commission has outlined a “three-firsts” principle: cargo before passengers, segregation before integration and suburban before urban.

“Safety is the foremost prerequisite for the development of the low-altitude economy,” commission spokesperson Li Chao said in April.

Safety also goes hand in hand with public trust, especially as companies eye passenger operations in crowded city skies, as industry experts and company insiders point out.

Industry insiders say regulators have “deliberately cooled the temperature” after a surge of test flights in 2022 and 2023. According to them, internal guidance now limits new passenger-carrying operations until at least 2026.

“The system is too new and not yet complete, and regulators have a red-line mindset - they’re afraid companies might rush in without proper safeguards,” He from EHang told CNA.

“Even if technology and policy are ready, people need time to trust a new mode of flight … without transparency on safety or insurance, it’s difficult for such a young industry to win real buy-in,” he said.

Safety scares have reinforced that caution. In September, two XPeng AeroHT aircraft collided mid-air during a rehearsal for the Changchun Airshow, with one catching fire on landing.

Days later, Chinese influencer Tang Feiji died in Sichuan after crashing his ultralight aircraft during a livestream. Analysts said both incidents underscored the tension between innovation and safety.

“In the West, safety is earned through flying,” Xu from NexAvian, which is currently working with Chinese clients, told CNA.

“But the Chinese take a different approach … the government is freaking out before you do.”

SLOWLY BUT STEADILY

For now, commercial applications are centred on down-to-earth uses, with agricultural and industrial drones being the most mature fields.

In Hebei’s Qinhuangdao, drones now carry harvests down mountain slopes once navigated on foot, while in southern Xinjiang, 21m “steel-wing” sprayers conduct precise defoliant operations ahead of cotton picking - doubling efficiency compared with traditional machines.

Shenzhen-based DJI, one of China’s earliest drone innovators, told CNA that policy momentum is finally catching up with what the private sector has been building for years.

“We’ve spent more than a decade testing reliability and safety in real-world scenarios, from crop-spraying and power-grid patrols to firefighting and emergency rescue,” a spokesperson said.

“In cities, approvals are still strict, but in rural and industrial zones, applications are scaling fast.”

The “boring”, day-to-day uses are where the money currently is, said Goh from UOB Kay Hian.

“These deliver immediate returns and build the case for larger ambitions later.”

Still, the path to wider commercial success is uneven, with some younger firms yet to see returns as they inch through the certification process.

One such company is ZD Space X, a Guangzhou-based start-up that has invested about 30 million yuan and is still in the pilot-to-certification stage.

“Most companies in our sector are still not profitable at this stage, it reflects the current phase of the industry,” its chief executive Ma Xiao told CNA.

He highlighted that tourism and cargo are the most feasible scenarios for now, although he believes “real economic lift” will eventually come from passenger operations.

Against this skyline, business priorities are being reshaped as companies shift from experiments to endurance.

Companies once focused on passenger flights have shifted their focus to sightseeing routes and carrying cargo, where approvals are easier and the relative risk is lower, according to industry players.

He, the vice-president of EHang, said such pilot programmes are crucial to building confidence. The company operates short sightseeing flights in Guangzhou and Hefei.

“Tourist areas give us a safer middle ground,” he said. “They generate real revenue and feedback while helping regulators refine policies before flights expand into city airspace.”

Another firm, Beijing-based Movector X, is currently focusing on low-altitude drones with a payload capacity of about 150 kg, with most of its orders coming from logistics and emergency-rescue operations.

“Carrying people must wait for airworthiness and safety rules to catch up,” Ma Ning, the chief marketing officer for Movector X, told CNA.

She added that cargo flights can receive operational clearance within a day, compared with years for passenger certification.

Some firms are learning from peers. “Fengfei (Aviation) switched from passenger to cargo and got certified in under a year,” said Ma Xiao from ZD Space X.

“We’re following that path.”

In the meantime, the company, still in its first funding round, has launched licensed drone-pilot training programmes to generate revenue while waiting for approvals.

“Training gives us both cash flow and talent,” said Ma Xiao. “These are the people who will one day operate cargo and passenger eVTOLs safely once the rules are ready.”

NEXT STOP: SOUTHEAST ASIA

While domestic airspace opens in stages, Chinese firms are probing overseas skies for opportunities.

Several companies told CNA they have fielded enquiries from Indonesia for cross-coastal hops moving people and goods.

The market is promising but thin: industry data shows Indonesia accounts for about 4 per cent of Asia Pacific’s helicopter fleet, highlighting both potential and readiness gaps.

Asha Wadya Saelan, founder of the Indonesian Unmanned System & Technology Association and chief operating officer of BETA-UAS, which develops and manufactures unmanned aerial vehicles, said the route to exports starts conservatively.

“Exports make sense in phases. Trials and cargo come first. Passenger service follows once Indonesia validates certificates and the ground ecosystem is ready,” he told CNA.

Indonesia’s framework already allows special authorisations for pilots while operators build experience. “Success depends on certification alignment, operator readiness, and integration of unmanned traffic management with traditional air control,” he said.

In Thailand, EHang has launched an Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) “sandbox” with the Civil Aviation Authority and local partners - a pilot zone for a new generation of air transport systems that use electric or hybrid-electric aircraft.

The trials are running in Bangkok, with plans to extend to Pattaya, Koh Larn, Phuket and Koh Samui.

According to the company, these overseas pilots mirror its cautious rollout at home: markets need real operating data before daily services can follow. As one executive put it to CNA, the goal is to fly under supervision, gather evidence and earn confidence.

Analysts said the overseas turn is not just about sales. As Xu from NexAvian noted, introducing a new vehicle category demands local learning: weather, maintenance capacity and public acceptance.

For Chinese firms, early Southeast Asian routes double as living laboratories - places to refine procedures, train crews and align certificates - while China’s “carrying goods, scenic site first” approach plays out at home.

Singapore has been playing a coordinating role in shaping Asia’s rulebook for air taxis and drones.

The Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore (CAAS) first mooted a set of shared guidelines in November 2023. Subsequently, the reference materials were jointly developed by CAAS and 23 regional counterparts and adopted in July this year.

“The group will also submit the reference materials to the International Civil Aviation Organization for reference for global adoption,” CAAS said in a statement on Jul 17.

At the same time, low-altitude forays in Singapore have faced turbulence.

In 2023, German company Volocopter postponed its air taxi launch at the Marina Bay area due to funding shortfalls.

The firm eventually filed for insolvency in December 2024 before being subsequently reorganised under Diamond Aircraft Group Austria, part of China’s Wanfeng Auto Holding Group.

Xu noted that under such an asset deal, previous agreements lapse unless re-signed, meaning Singapore may need a new partner to restart air taxi trials.

Still, Singapore’s strong institutions and strategic location make it a natural testbed for the emerging sector, according to Xu.

AAM and the low-altitude economy are expected to feature prominently at the Singapore Airshow in 2026.

CLEARER SKIES AHEAD?

Globally, the low-altitude race is still taking shape.

In the United States, the Donald Trump administration has been easing restrictions on commercial drones flying beyond visual line of sight, a move expected to speed up their integration into national airspace.

The US aviation regulator, the Federal Aviation Administration, approved more than 27,000 such flights in 2023, up from just 1,300 in 2020.

In Europe, regulators are working to harmonise eVTOL certification standards across five nations by 2027.

Meanwhile, Dubai is laying out its first air-taxi corridors for launch in 2026.

Japan’s Osaka region has announced eVTOL route plans targeting 2028 and beyond, with the city having hosted demonstrations at an international exhibition, Expo 2025, earlier this year.

China’s flight path for the industry is more coordinated, analysts said.

“Everyone responds to the call to action by the head of state,” said NexAvian’s Xu, even as he noted that the same top-down speed can also lead to pauses whenever regulators tighten oversight.

EHang’s He outlined a four-stage road map - pilot deployments, affordable “mass ridership”, city-wide normalised operations and finally large-scale safe operations. He expects the company to enter its second stage in 2026 as more cities gain commercial approval.

The stakes are significant for the world’s second-largest economy.

Success in the low-altitude economy - and realising its touted trillions in commercial potential - could help cushion China against domestic headwinds, from sluggish consumer spending and rising youth unemployment to longer-term demographic strains.

But the implications stretch well beyond China. From setting certification standards to reshaping supply chains in batteries, avionics and air-traffic systems, Beijing’s push could influence how the next generation of low-altitude flight takes off worldwide.

For all the potential, the runway ahead is set to be long. Industry players expect it will take another one to two years before mid-sized cargo craft can be fully certified, and at least three to five years before passenger flights expand beyond limited pilot routes.

For entrepreneurs like Hope Loong’s Pan, that wait is baked into the business model.

“I can’t wait two or three years for full certification before selling,” he said.

“So we keep testing and feeding data to regulators, and in the meantime, we keep the lights on with rentals and demonstrations”.