IN FOCUS: In this China-Russia border town, travellers are back but why aren’t locals thrilled yet?

Day trippers and tourists might be returning, but merchants in China’s northeastern Suifenhe town tell CNA the long-awaited spending boom has yet to materialise.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SUIFENHE, Heilongjiang: Li Penglin wasn’t planning to make history. He happened to be scrolling through news reports in December when a headline caught his eye: Russian President Vladimir Putin had approved visa-free entry for Chinese tourists.

The next morning, Li was at the border.

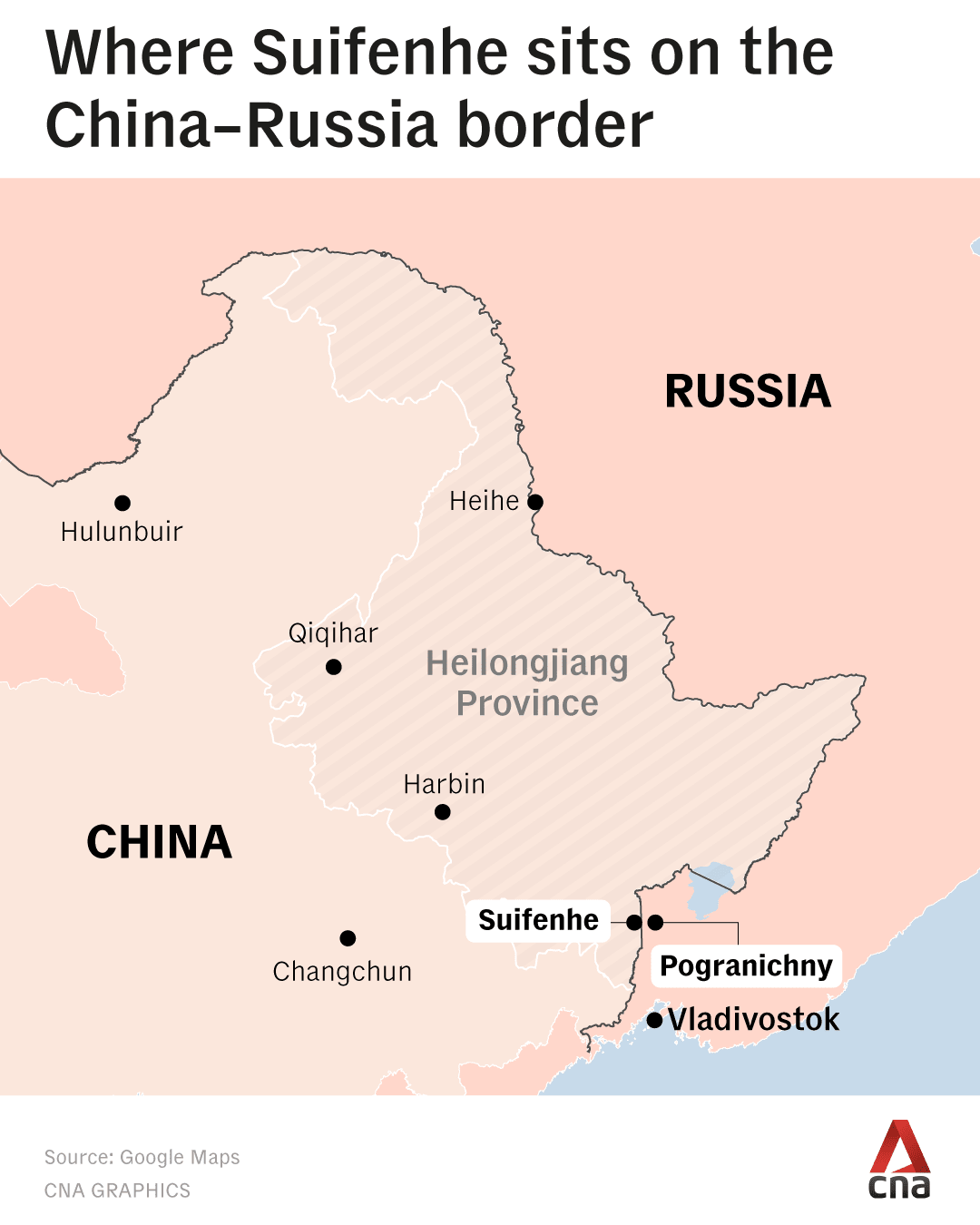

The 27-year-old, who works in China’s e-sports industry, lives in Suifenhe, where he also grew up - a county-level city in Heilongjiang province in northernmost China, located merely kilometres away from the border with Russia.

Curiosity drove him to try his luck, Li said - and he wanted to see whether the policy had taken effect.

His arrival took immigration officers by surprise, he added. Phone calls were made and several checks were done before officials gave the green light.

He became the first Chinese national to enter Russia under the new visa-free arrangement - a claim he later relayed to CNA and said border officials had repeated to him.

For Li, the trip wasn’t about making a statement but about satisfying a familiar pull. He had visited Russia several times before and said he was drawn to its food and culture.

“It feels different from China. The food, the streets, the atmosphere - it all feels distinct and closer to that of Europe,” he told CNA.

“It’s just minutes away, but the experience is authentic and different.”

This time, his destination was Grodekovo station in Pogranichny, Primorsky Krai - a modest Russian border town accessible by a 30-minute bus ride from the Suifenhe checkpoint.

Interactions with locals felt easy and friendly, Li said.

His quiet crossing reflects a larger shift unfolding along China’s northeastern edge.

After Beijing began visa-free entry to Russian citizens in September - and with reciprocal travel now running both ways since December - Suifenhe has become frontline testing grounds of warming Chinese-Russian ties - how they are translating into movement, trade and realities on the ground.

Among China’s landlocked neighbours, Russia is the only country to have reciprocated recent visa-free access.

Another comparable policy was visa-free travel by land with Kazakhstan - rolled out in late 2023.

Russia’s opening, however, comes against the backdrop of its ongoing war with Ukraine, sanctions and a deeper strategic tilt between Beijing and Moscow.

Since the war in Ukraine and the Western sanctions that followed, Russia’s pivot east towards China has reshaped daily life in Suifenhe - from the surge in car exports to a rise in Russian shoppers seeking goods and services no longer easily available at home.

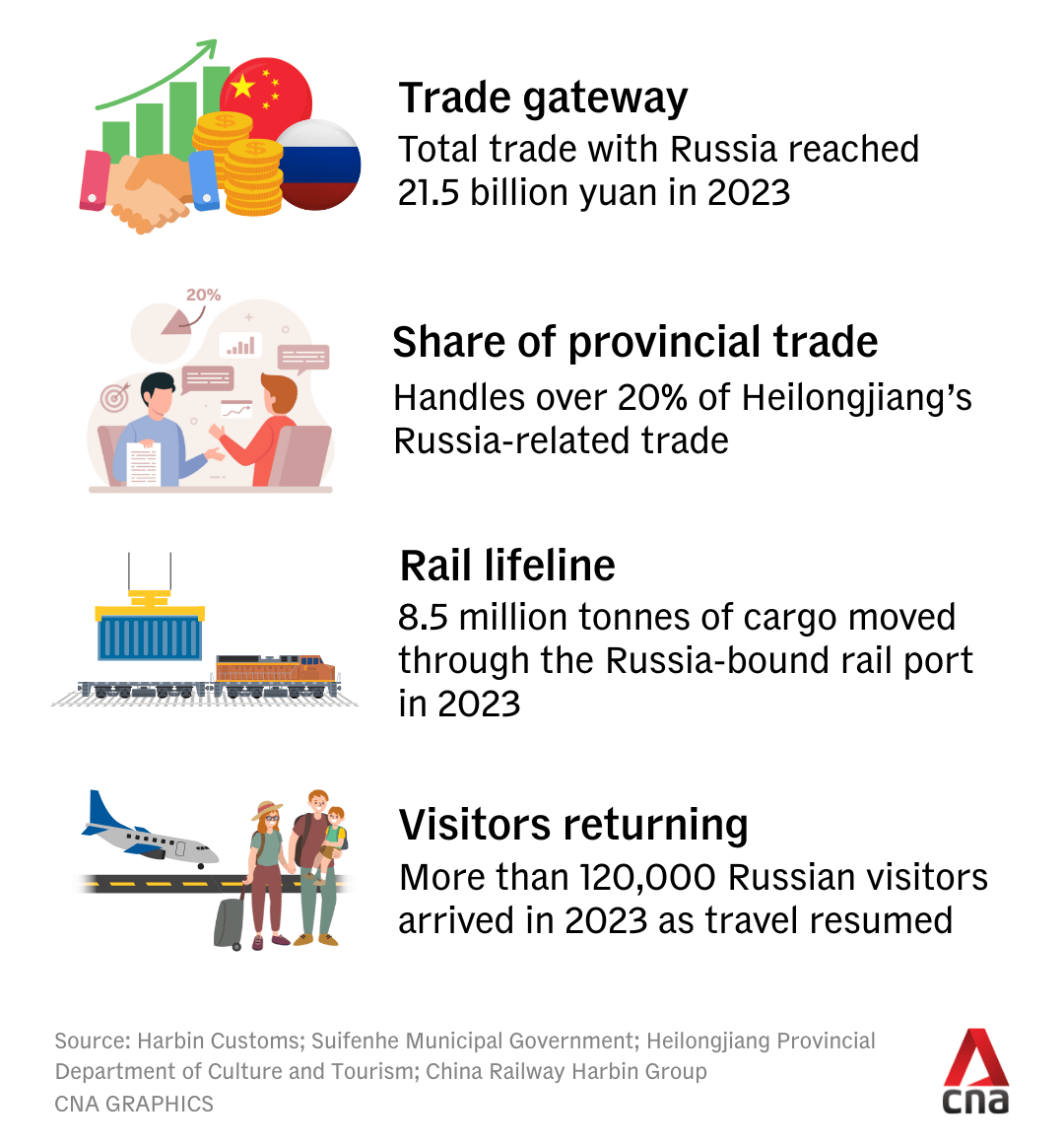

In 2023, the Chinese border city handled around 21.5 billion yuan (US$3.07 billion) in trade with Russia - more than one-fifth of Heilongjiang’s Russia-related trade.

Overall China-Russia trade surged in 2023, reaching a record US$240.1 billion - driven by Russia's pivot away from Western markets and its increasing use of yuan for transactions.

Trade reached new highs of US$244.8 billion in 2024, according to China’s customs data - driven by Russia’s increased demand for Chinese-manufactured goods like cars and electronics.

Against that backdrop, Suifenhe’s Russia-linked trade in 2023 amounts to roughly 1.27 per cent of the bilateral total.

Although Suifenhe’s share of overall China-Russia trade is in line with expectations for a border city, its role is more pronounced in specific segments.

A report noted that in 2023, cargo throughput at the Suifenhe port accounted for about 65 per cent of Heilongjiang province’s total, while its trade with Russia made up nearly 40 per cent of the province’s non-oil Russia-related trade - highlighting the city’s importance as a key hub for general merchandise and non-energy trade along the China-Russia border.

But the effects of this geopolitical alignment have been uneven in Suifenhe.

Russian visitors are returning. Chinese tourists are crossing over more spontaneously. Businesses from car exporters to coal traders have clustered along the border.

Yet shopkeepers and traders say the long-awaited boom has not arrived as suddenly as many have hoped.

Policies open doors but spending power, logistics and broader economic pressures ultimately determine what actually passes through.

A TOWN SHAPED BY CHINA-RUSSIA TIES

Suifenhe is one of the closest Chinese land gateways to Russia.

Perched on China’s northeastern edge, it takes less than 20 minutes to reach the border from the city centre.

Geography has long defined the town’s purpose. Rail links tied it into cross-border commerce as early as the late Qing dynasty, and that legacy endures today.

With a local economy closely linked to its northern neighbour, the town remains one of China’s most important trade gateways with Russia.

Imports - dominated by timber, coal, fertiliser and seafood - totalled roughly 16.8 billion yuan. Exports of machinery, textiles, daily goods, fruits and vegetables reached 8.8 billion yuan.

Russia’s imprint is visible across the local economy. More than 2,800 foreign trade enterprises are registered in Suifenhe, about 80 per cent of them engaged in Russia-related business.

The city’s comprehensive bonded zone handled roughly 4.2 billion yuan in trade in 2023 - with more than 90 per cent linked to Russia. Much of that trade moves by rail.

Suifenhe also hosts one of China’s largest rail ports to Russia, with annual capacity reaching millions of tonnes.

Rail freight volumes reached about 8.5 million tonnes in 2023 - mostly coal and timber, while road ports handled another 450,000 tonnes of goods, according to China Railway Harbin Group figures.

Entire industries have grown around this cross-border flow. Suifenhe imports nearly 4 million cubic metres of Russian timber annually - nearly 30 per cent of China’s total timber imports from Russia - supporting a local wood-processing sector worth roughly 6.5 billion yuan.

Cross-border e-commerce remains small but is growing. A pilot China-Russia cross-border e-commerce clearance platform processes tens of thousands of parcels a day for Russia-related orders.

Retail and tourism are similarly Russia-facing. Before the pandemic, Suifenhe received more than 300,000 Russian visitors annually. Arrivals recovered to around 120,000 in 2023 and accelerated after China’s visa-free trial for Russians and the easing of cross-border restrictions.

The city is dotted with Russian-language signs, restaurants and shops. Market regulators say more than 500 stores sell Russian food and consumer goods, with annual sales estimated to be billions of yuan.

Supporting services - from currency exchange outlets and ruble settlement banks to Russian-language legal and logistics consultants - have grown alongside demand.

For Wang Jianpeng, president of the Suifenhe Authentic Russian Goods Import Association, the change is unmistakable.

“Our association grew from 20 or 30 members a decade ago to more than 100 now,” he told CNA, adding that the overall volume of Russia-linked imports and distribution “has definitely increased”.

But Wang is cautious. “When the exchange rate moves, the market can grow - or disappear,” he said.

FUSS-FREE JOURNEYS ON A WHIM

Since 2023, Beijing and Moscow have elevated bilateral cooperation across trade, transport and cultural exchanges.

When President Xi Jinping met Putin in Moscow on May 8, 2025, both leaders singled out people-to-people ties as a core pillar of the relationship.

On the ground, visa-free travel, alongside expanded trade and transport links, has turned day trips and short visits - that once required careful planning - into journeys that can be made on a whim.

If trade figures and freight volumes show how closely Suifenhe is bound to Russia, the streets show how that relationship is lived.

Rather than mass tourism, the border is seeing a continuation - practical travellers making short, targeted shopping trips and even grocery runs, students and athletes on brief stays, families on day trips, and traders moving goods.

Among them is Anna Ulchenko, a 37-year-old school teacher from Vladivostok. She travelled to Suifenhe to stock up on construction fittings and household items to rebuild her home.

Even after factoring in transport and shipping, she said, Chinese prices still remain attractive.

“Many things are still around 30 to 50 per cent cheaper here,” she said - a steal even if it meant enduring winter cold that dipped to minus 20 degrees Celsius.

Over the past year, the Russian ruble has strengthened by more than 20 per cent against the Chinese yuan, narrowing the price gap that once drew bargain hunters.

But for Ulchenko, availability matters as much as cost. “In Russia, the selection is limited,” she said. “Here, Chinese merchants will do their utmost to satisfy your needs.”

Her recent trip to China was also social. She travelled with her son and a family friend’s child. “It’s a good break,” she said. “We shop, we eat, we spend time (together).”

Another Russian traveller, who wanted to only be identified by her first name Elena, makes trips to Suifenhe every month.

The 33-year-old visits friends, stocks up on essentials and uses local medical services like dentist and clinical visits. “Medical technology is very good and prices are at least 30 per cent cheaper,” she told CNA.

“From registration to treatment, (there are also) staff who speak Russian who make you feel at ease,” she added.

Younger travellers combine sports and shopping. Viktor Zolotukhin, a Russian university student, was recently in Suifenhe for a skiing competition and used the trip to buy clothes and gifts. “Things are simply more value for money here,” he said. “Even small purchases add up.”

He also noted how some local Chinese merchants were accepting Russian rubles, as part of an experimental pilot.

“You can pay in rubles,” Zolotukhin said. “That makes shopping easier.”

NEW BORDER ECONOMY

If ruble payments and visa rules have made short trips easier, the deeper shift lies in what now moves across the border - and why.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the wave of Western sanctions that followed, demand has shifted eastward.

The town of Suifenhe has emerged as a node in that reconfigured supply chain.

One of the most visible changes is the surge in vehicle exports.

“Unfortunately, the car industry in Russia is not as well developed as in other countries,” said Igor Sadov, a Russian interpreter working for a foreign firm with a branch in Suifenhe.

He told CNA that many Western brands left the Russian market "after sanctions were introduced against Russia".

Options were “very limited”, he said, and China’s auto industry is "mature and innovative". “For customers who wanted more options, they look to China,” Sadov said.

Data from the China Automobile Dealers Association shows that China exported about 420,000 used vehicles to Russia in 2023 - more than five times the previous year - with exports remaining high into 2024.

Manzhouli, also located on the border with Russia and near Mongolia, has been one of the main gateways for used car exports, handling more than 60 per cent of shipments in 2023.

But Suifenhe and other border towns have increasingly become feeders and service hubs along the same corridor.

Infrastructure is China’s key advantage, said Sadov.

“There is a complete system here - vehicle inspection, certification, logistics,” he added.

“Companies can focus on orders. The rest is in place.”

That system, however, depends on labour willing to endure long hours and difficult conditions.

Wang, a 50-year-old truck driver hauling vehicles for export, said he signed up after seeing job recruitment adverts. A former farm worker, he said this was only his third run.

Each trip takes six to eight hours each way, often through freezing winter conditions and terrain, he said.

Language barriers and customs procedures also add to the strain.

“It’s very cold, the roads are tough, and language is a big problem,” he said, adding that he often “struggles” to communicate with customs officers and port staff.

“Many drivers quit. That’s why demand for (new) drivers remains high.”

Energy flows have followed a similar pivot. As European buyers closed off, Russia redirected coal and crude eastward.

China has become a major buyer of Russian coal and crude, according to customs and international energy trackers.

That shift has fuelled the rapid growth of small coal trading firms in northeast Chinese border cities and towns.

Xing, a Russian coal seller operating out of nearby Dongning, said competition has intensified over the past year.

“Many new coal companies have been set up,” he said. “Everyone is chasing the same Russian supply now.”

For traders such as Wang Jianpeng, the new border economy presents both opportunity and pressure.

“Volumes have increased but volatility is a constant risk,” he said. “Exchange-rate swings and rising costs can quickly erase (profit) margins.”

The border economy that has formed around cars, coal, timber and cross-border retail was not the product of long-term regional planning - but of geopolitical shock.

Sanctions, supply-chain dislocations and diplomatic alignment have opened new channels.

But workers, small traders and logistics firms who populate those channels face thin margins, high turnover and shifting regulations.

WHY THE BOOM HAS NOT RETURNED

And yet, the reopening of crossings and the emergence of new trade has not produced the instant, town-wide boom many expected. On the ground, merchant optimism is tempered by caution.

Zhou Rimin, who runs a spectacles shop in Qingyun shopping complex, arrived in Suifenhe from Jiangxi in the late 1990s - riding an earlier wave of Russian trade.

“Back then, buses would come one after another,” he recalled.

“Russian visitors were excited by Chinese products because Russia’s light and medium manufacturing industries were weak,” he said.

“Goods such as spectacles had more variety and were cheaper here. I used to restock popular frames every two weeks.”

Russia’s economy has been dominated by energy, raw materials and heavy industry, while light manufacturing - clothing, household goods, consumer electronics - lags behind China’s capacity - a contrast repeatedly noted by international institutions like the World Bank and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

But advantage no longer guarantees sales, said Zhou.

Visitor numbers never fully recovered after the pandemic and the outbreak of the Ukraine war.

“Even after visa-free travel started, arrivals haven’t come back the way people hoped,” he said.

“There are barely any customers.”

The slowdown is reflected in rental prices.

A local tailor, identified only by his surname Wang, said monthly rent once peaked at about 500,000 yuan during the boom years.

Today, after renegotiations and landlord concessions, it remains below 30,000 yuan.

“The size of the rent cut mirrors the drop in sales,” he said. “Those who do come are spending less.”

Many merchants point to a weaker and more cautious Russian consumer.

While the ruble has strengthened against the yuan over the past year, it remains far below levels seen before 2014 - when Russia was first hit by Western sanctions following the annexation of Crimea.

Combined with sanctions, rising costs and wage pressures, that has shrunk shopping baskets.

“People are choosing lower-value items and are thinking carefully before buying,” Wang said.

“Their wages haven’t really gone up, and the economy in Russia isn’t good.”

Another problem is the spread of counterfeit goods.

Zhang Yanyan, who runs a Russian restaurant in Suifenhe and also operates a hotel in Vladivostok, said renewed interest in Russian products had produced a flood of imitation “Russian” goods in markets across the border.

“There’s been so much publicity that some people avoid buying Russian products because they fear fakes,” she said.

“Authentic importers suffer delays and extra scrutiny when counterfeit goods proliferate.”

The problem has drawn regulatory attention. Chinese market authorities launched inspections in several border cities to clamp down on shops falsely labelling goods as Russian, while Russian diplomatic missions in China have repeatedly warned consumers about counterfeits.

For legitimate importers, this added scrutiny means extra checks, seizures and delays - all of which eat into already thin margins.

For Wang Jianpeng, the head of the association that represents many of these traders, the picture is clear: visa-free travel has reopened doors, but it cannot, on its own, recreate the old conditions that once powered Suifenhe’s retail boom.

“Movement has returned but it doesn’t automatically mean consumption,” he said.

BETTING ON THE LONG GAME

The local response in Suifenhe is pragmatic. Many merchants and residents are recalibrating their expectations, spreading risk and betting on steady gains rather than a sudden surge.

For Wang Jianpeng, one practical change stands out: cheaper transport.

Cross-border bus services are limited and ticket prices remain high with few operators. “There’s no real competition right now, so prices stay stiff,” he said.

“If authorities can help bring in more operators and lower fares, it would directly encourage more people to come. That would really help tourism here.”

That logic has pushed some young locals to return.

Zhao Xian, who spent seven years working in Beijing in government-related roles, returned to Suifenhe with his wife and opened a cafe in May 2025.

He hasn’t seen tourists arriving in large numbers, even with the new visa-free travel arrangements, but he remains hopeful.

China is “opening further to the north and far east”, he said - creating “real opportunities”.

Foot traffic has been gradually rising. “From almost no tourists, numbers have been slowly increasing,” he said.

“Young people are returning because they see opportunities. Culture follows the economy.”

Zhao remains realistic about timelines.

“Industrial parks don’t become economies overnight. Policy turning into economic results takes time,” he said.

Local authorities are taking action. In December, Suifenhe’s government rolled out several initiatives aimed at Russian visitors, part of a broader effort to convert policy momentum into sustained economic activity.

These included a streamlined scheme allowing Russian tourists to rent cars more easily for self-driving within the city, as well as the opening of a new art gallery and a snow-ski compound targeted mainly at travellers from Russia.

For Zhang Yanyan, the timing could not be better.

Her friend Aida, 62, moved to Suifenhe from Vladivostok two years ago and now helps out in Zhang’s restaurant. She has adapted well to life in China and says Suifenhe is her “second home.”

“I am used to living here and meeting Chinese people in the restaurant,” Annie said. “I hope Suifenhe becomes lively again as China-Russia ties continue to improve. More people-to-people policies will benefit ordinary people on both sides.”

Some businesses are adapting their models.

Retailers that once relied on bulk tourist spending now mix wholesale services for Russian merchants, online order fulfilment and targeted promotions.

Car export firms have diversified their services, expanding into logistics, inspection and certification.

“When people (learn of) policy changes, they make choices to travel, order and invest,” said trade association head Wang Jianpeng.

“But policy is only the first step - supply chains, transport costs, exchange rates, enforcement against counterfeits - these are things that decide whether an idea becomes income.”

For the merchants and residents, Suifenhe’s future may depend less on sudden surges than on steadier, incremental gains - built through repeated visits, trust and familiarity over time.

Cafe owner Zhao Xian believes any economic recovery is more likely to be gradual than dramatic.

He remembers a Suifenhe shaped by constant exchange - when Russian voices filled the streets and the border felt more like a meeting point than a geographical line.

“In the past, people and goods moved together - that’s when the town felt most alive,” Zhao said.

And as ties between China and Russia deepen again, he hopes Suifenhe will rediscover that balance - and with it, better days ahead.