Commentary: China does just enough to support Russia, same as the West does for Ukraine

China is officially neutral on the war in Ukraine, but it has been crucial in preventing Russia’s international isolation, says international security professor Stefan Wolff.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

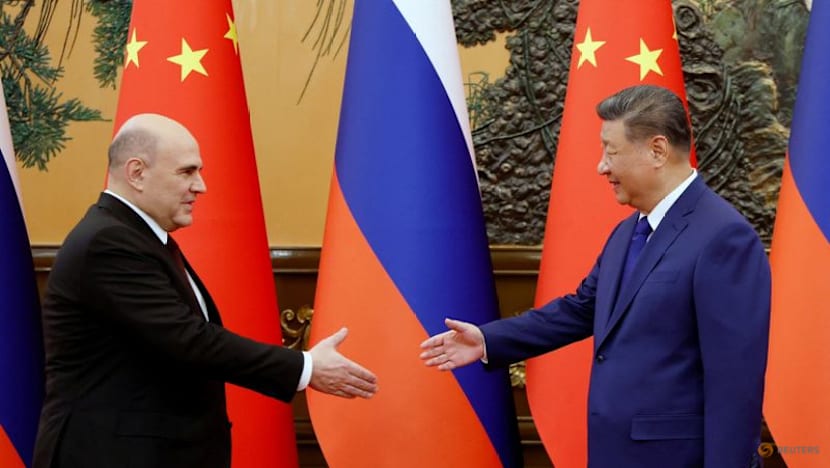

BIRMINGHAM: Considering Chinese President Xi Jinping and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin now meet semi-regularly – twice already in 2025 – the annual meetings of their heads of government could be considered fairly unremarkable, routine events. When Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin visited China on Nov 3 and 4 at the invitation of Premier Li Qiang, it was the 30th iteration of a practice that started in the wake of the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

But since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, these meetings have taken on a significant degree of geopolitical importance.

Together with the two countries’ interactions in organisations they dominate, like BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the meetings serve as both symbolic reminders and operational enablers of the so-called no-limits partnership between Moscow and Beijing.

US SANCTIONS ON RUSSIAN OIL

Mr Mishustin’s visit to Hangzhou and Beijing, which included an audience with Mr Xi, must be seen in a broader context.

It followed the first United States-China presidential summit of Donald Trump’s second term in office. On Oct 30 in South Korea, Mr Trump and Mr Xi struck a temporary truce in their escalating trade war, climbing down on import tariffs and rare earth export controls.

While the two leaders discussed Ukraine, Mr Trump said that they did not touch on the subject of China buying Russian oil, which has helped fund the Kremlin’s war.

On Oct 23, Mr Trump announced US sanctions on two of Russia’s major oil companies – Rosneft and Lukoil – in a bid to pressure Mr Putin to the negotiating table. Tightening the screws on Russia was a departure from Mr Trump’s approach so far and the sanctions are scheduled to take full effect on Nov 21.

As a result, there have been some indications that state-owned Chinese refineries have begun to unravel at least some of their contracts with Russian suppliers. This may well be enough for Mr Trump to avoid imposing any further secondary sanctions on China which might otherwise undermine his efforts to negotiate a more favourable trade relationship with China.

SEVERAL LIFELINES FOR RUSSIA

Even if Mr Trump were more determined to use America’s significant economic leverage in pursuit of peace in Ukraine, China is unlikely to bow to any pressure.

On the contrary, the joint communique issued after Mr Li and Mr Mishustin’s meeting was unequivocal in reaffirming that “China and Russia will always regard each other as priority partners and … properly respond to external challenges,” including by making “all necessary efforts to cooperate with each other in opposing unilateral coercive measures”.

The joint communique also repeated the now customary formula that “China supports Russia in safeguarding its own security and stability, national development and prosperity, sovereignty and territorial integrity, and opposes interference in Russia's internal affairs by external forces”.

Rhetoric to one side, however, there is nothing to indicate a major step-change in Chinese support for Russia. Beijing continues to provide Moscow with several lifelines.

China remains one of the major importers of Russian oil and gas which provides much-needed foreign income for the Russian treasury. China is also reportedly a major supplier of so-called dual-use goods, including semiconductors and machine tools that are critical to sustaining Russia’s defence industrial base.

A database of joint military exercises between Russia and China has recorded over 117 of them since 2003, with one-third over the last three-and-a-half years since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

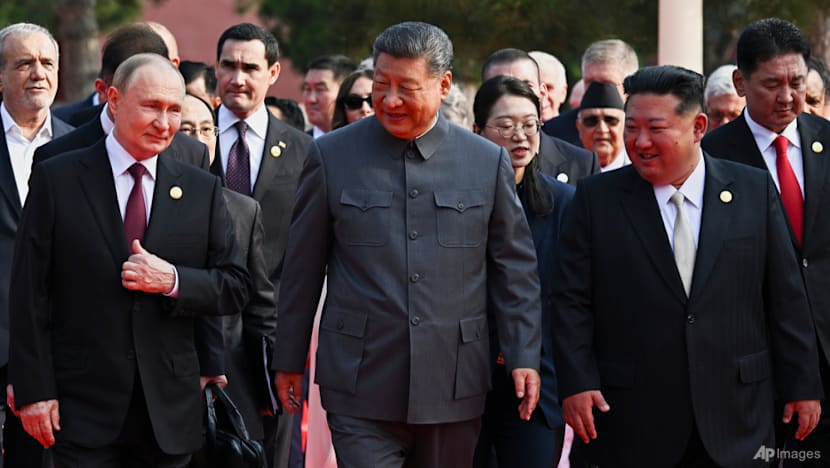

After some initial concerns, China appears to have acquiesced to the military aid that North Korea has provided to Russia to date. This was evident in the bonhomie between the three countries’ leaders at the celebrations of the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in Beijing in September.

And last, China has been crucial in preventing Russia’s international isolation, by maintaining high-level, high-visibility links at the bilateral level and through multilateral efforts.

OFFICIALLY NEUTRAL

Officially, China remains committed to its February 2023 position paper on Ukraine, which starts with the assertion that the “sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all countries must be effectively upheld”. Beyond this rhetoric, however, China has done little to work towards an end to the war.

On the contrary, and the outcome of the Russia-China prime ministerial meeting suggests this, China’s approach appears to be aimed at providing enough support for Russia to help without directly and overtly supplying arms.

In other words, China, much like the West does with Ukraine, likely does just enough to keep Russia's war machine going but stops short of any game-changing moves.

This is partly the result of Western pressure and the need to maintain a reasonable level of diplomatic and economic relations with both the United States and the European Union. But the continuation of Russia’s war against Ukraine also serves Chinese interests in another, equally important way.

It keeps the US at least partly engaged in Europe, and thus unable to fully commit to the Indo-Pacific and the rivalry between Washington and Beijing. And it keeps Russia firmly dependent on China, ensuring that Moscow will remain Beijing’s junior partner in a new bipolar order, rather than become a great power in its own right in a multi-polar international system.

This struggle over the future shape of the international order is far from over – and it will in part be decided on the battlefields of Ukraine where the guns are unlikely to fall silent anytime soon.

Stefan Wolff is Professor of International Security at the University of Birmingham and Head of the Department of Political Science and International Studies.