Commentary: US and China as co-equals? Trump-Xi meeting hints at new G2 world

Looking beyond the limited truce in this tariff war, the Busan meeting was a symbolic elevation of China, says former SCMP editor-in-chief Wang Xiangwei.

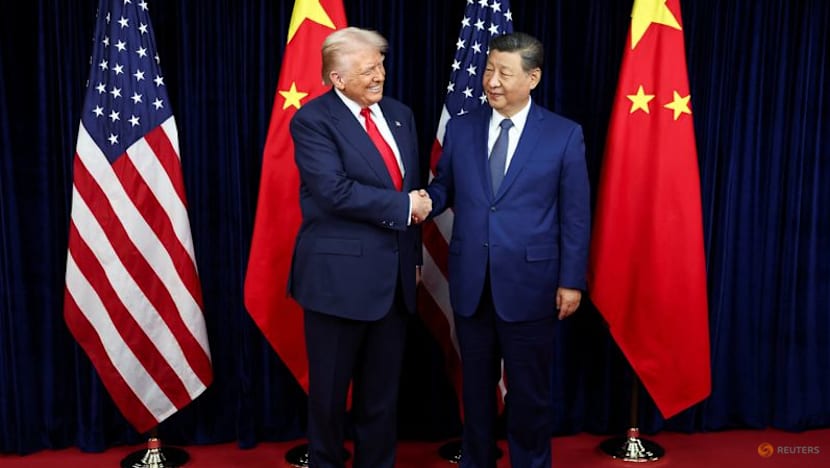

US President Donald Trump shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Busan, South Korea. (Photo: Reuters/Evelyn Hockstein)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

HONG KONG: On the face of it, the much-anticipated meeting between China’s President Xi Jinping and his American counterpart Donald Trump in Busan, South Korea on Thursday (Oct 30) delivered little by way of concrete breakthroughs.

Yet it may have quietly opened the door to a new modus vivendi: a Group of Two (G2) world in which China and the United States coordinate on some global problems while continuing to compete, even fiercely, on others.

True to form, Mr Trump called the leaders’ first face-to-face encounter in six years a “great success”, rating it “a 12 out of 10”. Beneath the hyperbole, the narrow deal-making was modest – a limited truce in the tariff war Mr Trump reignited in April.

According to official readouts, Washington agreed to cut fentanyl-related tariffs from 20 per cent to 10 per cent, trimming the total combined tariff rate from 57 per cent to 47 per cent – still higher than pre-trade war levels. Beijing, for its part, pledged to maintain rare earth exports under a one-year renewable arrangement and to restart purchases of US soybeans.

Contentious issues – ranging from the forced sale of TikTok to US restrictions on semiconductor exports – were punted to further negotiations.

THIS COLLABORATIVE TEASE

Equally notable was what the two leaders did not discuss.

By both sides’ accounts, Taiwan – the “core of the core” for Beijing and a perennial flashpoint – was absent from the agenda, a striking omission that may be a first for a US-China summit in decades. Instead, the leaders reportedly explored ways to work together to end the war in Ukraine.

Whether that signals tactical pragmatism or strategic ambiguity remains to be seen, but it underscores the emerging contours of a selective-cooperation model.

Mr Trump himself hailed it on social media as a “G2 meeting” that would usher in “everlasting peace and success”. A day after, in Malaysia, China’s Defence Minister Dong Jun met US counterpart Pete Hegseth, who echoed Mr Trump’s sentiment and pledged to “deconflict and de-escalate any problems that arise” between the two militaries.

It is this collaborative tease that elevates Busan beyond a photo-op, hinting at the resurrection of the G2 concept – a bipolar stewardship of global affairs by the world's two economic titans.

CONTEXT FOR DONALD TRUMP’S RHETORIC

To grasp the significance – and the differences from earlier iterations – some history helps.

Economist C Fred Bergsten sketched the G2 concept in 2004, primarily as an economic framework. It gained traction during the 2008 global financial crisis, when China’s massive stimulus stabilised its own economy and shored up global demand, cementing Beijing's bona fides as an indispensable player.

From Washington’s vantage point, a G2 approach was a savvy pitch: The “world’s workshop” should shoulder responsibility as a “responsible stakeholder”, helping maintain the system from which it benefited.

Beijing, however, saw risks. Many Chinese leaders suspected a trap that would drag China into burdensome global roles, distract from domestic development and alienate it from the developing world to which it felt it belonged. Deng Xiaoping’s dictum – “hide your strength, bide your time” – reinforced that caution.

The dance ended as Mr Xi consolidated power from 2012 onward and abandoned low-profile diplomacy for a more assertive stance.

Meanwhile, the US lurched toward containment: Mr Trump's first-term trade salvos in 2018 and former President Joe Biden's "high fence, small yard" tech clampdowns were all aimed at throttling China's economic, technological and military momentum, via alliances and export chokepoints.

The irony? Containment flopped. China’s technological and industrial upgrading continued, and Beijing’s leverage over critical supply chains – rare earths among them – became more salient.

It is in this context that Mr Trump’s current G2 rhetoric should be read.

A G2 OF CO-EQUALS

Beijing’s official reaction to the G2 label has been muted, but the underlying logic is hardly unwelcome in Zhongnanhai.

Beijing’s own thinking has evolved as well. For over a decade, Mr Xi has argued that the world is big enough for China and the United States to coexist as equals, a framing far removed from the hierarchical G2 some in Washington envisioned two decades ago.

If Busan is the beginning of G2 2.0, it is a G2 of co-equals, not patron and junior partner.

There are, however, hard constraints. Mr Trump’s G2 instincts are not new – he said last December that China and the United States “can together solve all of the problems of the world” – but his political style is mercurial.

The same feed that praises a G2 today can excoriate China tomorrow. That volatility partly explains Beijing’s cautious tone. Structural problems also lurk beneath the surface of the relationship: a ballooning US trade deficit with China; enduring US restrictions on high-end chips and tools; data security and platform governance; and, above all, Taiwan.

Without a broader understanding that addresses these issues, any G2 dynamic will be episodic.

GOOD NEWS FOR ASIA?

The calendar offers a window. Mr Trump is slated to visit China in April 2026, with a potential return visit by Mr Xi to the United States later that year. These could forge the comprehensive pact needed to anchor G2.

How should the world read the omission of Taiwan from Busan? It may be tactical, a decision to avoid blowing up a fragile restart, or it may signal that both sides prefer to manage that issue through quieter channels.

In the end, even a successful G2 will not be warm all the time. It will be a volatile tango, marked by recurring bouts of friction and periodic resets.

But if Washington and Beijing can institutionalise enough cooperation to stabilise the floor while competing responsibly above it, that alone would be good news – particularly for Asia, where the costs of miscalculation would be immediate and severe.

Even in its rawest form, though, this form of coexistence beats the alternative: untrammelled antagonism that allows disorder to fester and invites miscalculation.

Wang Xiangwei is a former Editor-in-Chief of South China Morning Post. He now teaches journalism at Hong Kong Baptist University.