China's youth are skipping Chinese New Year. Here’s why

Experts say “evolving social dynamics” are reshaping traditional customs as younger generations choose new ways to spend Chinese New Year.

Ah La (third from right) and friends celebrate Chinese New Year's Eve at the Unix Digital Nomad Community in Shenzhen. (Photo: Ah La)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Rather than return to her hometown in Guizhou for Chinese New Year, Ah La, a 31-year-old marketing communications manager, chose to spend the holidays at a digital nomad community in Shenzhen, along with nine others - playing games and hosting late night gatherings over hotpot by the sea.

Chinese New Year might be a time for family reunions but for millennials, the annual holiday is growing increasingly “repetitive”.

“The people you meet, topics you talk about and the food you eat at home are all very repetitive … Going home (every year) means repeating celebrations from the year before that all over again,” she told CNA, adding that the festive atmosphere "had really faded".

“What I value most is being able to connect with others who share similar interests,” she said.

Like Ah La, more youths are opting to spend the eight-day public holiday - from Jan 28 to Feb 4 - in other ways.

The annual chaotic travel rush, changing family dynamics and new lifestyles have been increasingly upending China’s most important holiday, experts say.

Also spending Chinese New Year away from home is Jiang Ningzhi, a 35-year-old business consultant from Suzhou city in the eastern Jiangsu province.

Every year, her family heads to a local hotel to host a grand reunion dinner for friends and relatives, a tradition she says has now become dull and routine.

This year, she wanted to celebrate the new year in a more traditional way, so she headed to Shuiku Village in Shanghai, a rural area that has become especially popular with young digital nomads looking to connect with nature and escape the stresses that come with city living.

She spent time chatting with locals, having a simple dinner and watching fireworks in the quiet township.

Having studied and worked abroad in the UK for the past five years, Jiang says she has grown used to being away from home during most festive periods.

While she visits her family in Suzhou as often as she can, returning home every Chinese New Year just isn’t necessary, she says.

Even her parents, both independent retirees, have been making alternate new year plans, spending the holiday abroad, she adds. This year, they were in sunny Hainan down south, known for its tropical climate and sandy beaches.

"Even if I go home, my parents might not be there so we’ve started spending the new year elsewhere in recent years," Jiang said.

“EVOLVING SOCIAL DYNAMICS”

Also called “Spring Festival” or the Lunar New Year in other parts of Asia, Chinese New Year is widely celebrated among Chinese communities around the world.

Steeped in tradition, its history in China dates back thousands of years and is widely regarded as being the important celebration of the year.

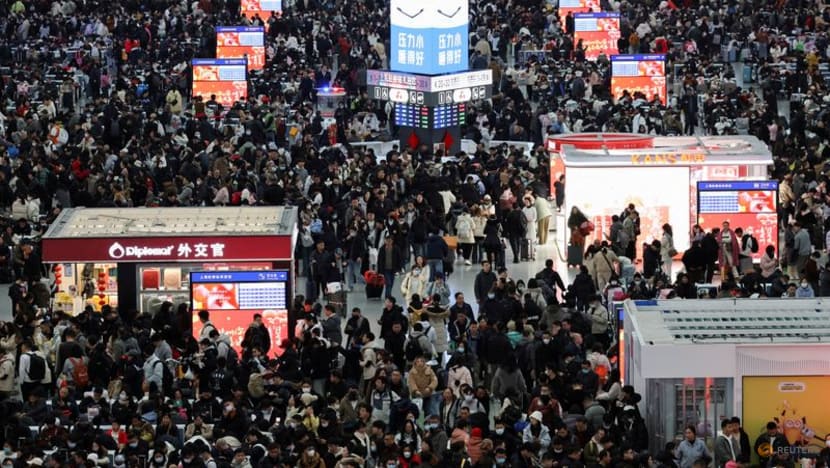

Every year, millions across the country return to their hometowns and villages from big cities to celebrate the holiday with family and friends.

Festivities revolve around family reunions, lavish meals and honouring ancestors as well as partaking in traditional activities such as making dumplings, parades and setting off firecrackers.

It is "no longer just a traditional holiday", said Dr Zhao Litao, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s East Asian Institute. "It has evolved into a ‘national festival’ uniting all Chinese people, including those overseas."

But as things continue to rapidly change in China, impacts of the economic slowdown continue to affect many. Rapid urbanisation, financial stress and shifting lifestyles and mindsets, especially among newer generations, are reshaping the way Chinese New Year is viewed and celebrated in the country, Dr Zhao said.

The shift could weaken intergenerational ties and reduce young people’s connection to rural roots over time. “Direct government intervention to reverse this trend would be difficult and might even be counterproductive,” Dr Zhao said.

“They are more attuned to urban living, which contrasts with the traditional, tightly-knit social fabric of rural communities.”

NOT JUST THE YOUTH

It isn’t just younger generations who are redefining how Chinese New Year should be celebrated.

Seniors and retirees are also embracing new ways, choosing to break away from tradition by venturing abroad to warmer climates, rather than staying in their hometowns.

It is the “reverse Spring Festival”, experts say, a trend that reflects changing attitudes toward retirement and the festive season.

One elderly couple from Shaanxi, aged 70 and 67, who began their retirement in 2021, have since spent every new year away, travelling to places like Haikou and Ledong in Hainan, Yangjiang in Guangdong, Beihai in Guangxi, and Xishuangbanna in Yunnan, with stays ranging from two weeks to six months.

A resident from Chongqing who wished to be known as Ms Yi, shared that her parents, who are in their early 60s, spend every Chinese New Year in warmer Chinese cities like Sanya or Xishuangbanna.

In 2013, they purchased a property in Xishuangbanna for 3,000 yuan (US$417) per square metre. Today, property prices there have doubled to 6,000–8,000 yuan per square metre.

“The decline of traditional customs has diminished the sense of ritual associated with celebrating Chinese New Year in one’s hometown, making it less appealing to younger generations,” said Zhou Wang, an associate professor at Nankai University’s Zhou Enlai School of Government in Tianjin.

He also noted that large families were also on the decline - a legacy of the one-child policy and ongoing demographic crisis.

“Large, extended families are increasingly rare in China, and there is a gradual estrangement among relatives,” he said.

“This runs counter to the Spring Festival's traditional message of family reunion.”

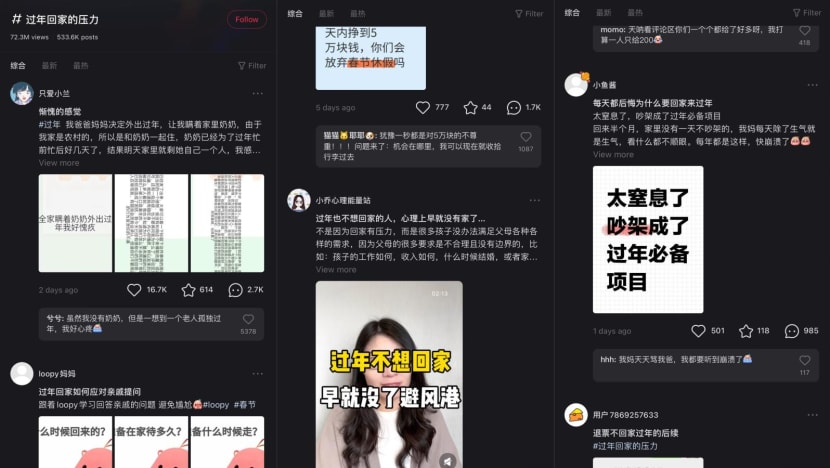

With more young Chinese increasingly adopting unconventional lifestyle choices, many have argued that they shouldn’t feel guilty for forgoing tradition.

“It’s about choosing the lifestyle we want,” said Wenhao, a 35-year-old freelancer who remains estranged from his family after cutting ties two years ago. “I don’t think we need to feel ashamed if we don’t spend Chinese New Year at home.”

In a Xiaohongshu post with over 1,500 likes, he shared his frustrations with societal expectations, including the pressure to marry and bear children.

“I used to spend every Spring Festival with my mother and valued the rituals - but now I feel more self-reliant and have realised that happiness can take many forms,” Wenhao told CNA.

“In the past, special foods or new clothes were things you could only enjoy during the New Year. Now, they’re accessible all year round,” he added.

Liu Yi, an associate professor and assistant dean at Sun Yat-sen University’s School of Tourism Management in Guangzhou, says the shift reflects broader social and economic changes as younger generations become increasingly rooted in cities.

“In the past, many young people moved to cities for work while their elderly parents remained in rural areas, so they would return home for the holidays,” he said.

“But over time, they settled in cities, started families, (some) even brought their parents to live with them. As a result, the need to return has significantly decreased,” he added.

Many, including families, are now choosing to use their holidays for vacations, Liu said, adding that Chinese New Year is a prime time for both domestic and international travel.

According to figures released by China’s Ministry of Transport, the number of cross-regional trips nationwide on Jan 21 reached 230.54 million, 15 per cent higher than the same period in 2024.

"In the past, those with lower incomes might have seen going home (for Chinese New Year) as a form of travel but as financial conditions improve, more families are prioritising travelling together instead of simply visiting their hometowns," Liu added.

For Jiang, being away for Chinese New Year isn’t abandoning tradition but rather, rediscovering it in new ways.

“In the countryside, you can truly feel the (new year spirit) as villagers return home to their families,” she said, at the same time relieved that he managed to escape overbearing relatives and also working through the holiday.