Babies for sale: An investigation into the Philippines’ adoption trade

In the Philippines, newborn children are traded under the guise of 'adoption'.

A Filipino infant sleeps in his mother's arms in Metro Manila, the hub of the Philippines' child adoption trade. (Photo: Pichayada Promchertchoo)

MANILA: Joyce is searching for a baby and she knows there must be someone in the slum who wants to sell their child.

The former midwife, whose real name is being withheld to protect her identity, has hooked up nearly 30 desperate mothers from Manila’s poorest neighbourhoods with people who have bought their newborns for ‘adoption’.

Boys and girls, Filipino and mixed-race, she has brokered them all. A few of them were even flown overseas where they might have joined a good family. But Joyce rarely knows where they ended up or if they are still alive. She does not really care. As soon as she got paid the commission, these babies were no longer her problem.

READ: ‘It’s not that I want to sell my kid. I just need money’ -The Philippine mothers who sell their babies

“If the mother is fine with it, why should I worry?” said the baby broker. She sits inside a van at a secluded parking lot not so far from her house.

Sometimes, when the arrangement is made while the mother’s still pregnant, we’ll give away the baby right after it is born. The new parents would be on stand-by to get it. Otherwise, it takes up to two weeks. That’s the longest.

Babies get sold quickly in the Philippines’ adoption trade - an illegal operation supplied by the country’s poorest of the poor. Widespread poverty and lack of access to education and basic healthcare has exposed women and children in impoverished communities to exploitation at the hands of human traffickers, who operate under the guise of adoption.

Children are normally traded when they are just days old, although the age can range up to a few months. Prices for an infant usually vary between US$100 and US$500. But according to Joyce’s experience, they can easily go over US$1,000 if the child is mixed-raced and considered ‘beautiful’.

“Those to be flown out are expensive,” she said, referring to one of the children she brokered.

“We agreed on 50,000 pesos (US$1,000) but the price went up because the baby was half-foreign. The mother didn’t expect it’d turn out that way. So, they added 10,000 pesos (US$200) as they found the child beautiful. That 10,000 pesos came to me, and the mother gave me an extra 5,000 pesos (US$100).”

The scale of the business is hard to determine. Still, cases sometimes emerge from the shadows to hit the headlines.

Last year, American national Jennifer Erin Talbot was caught at Manila's international airport while trying to smuggle a six-day old baby out of the Philippines in a bag. The boy was given to her in Davao City by his biological mother, who told officers she wanted him to be adopted.

The term ‘adoption’ is commonly used in the underground baby trade, where newborns are marketed through the whispers of their own mothers, relatives and baby brokers like Joyce. These criminals exist in a shady world, where they operate almost entirely by word of mouth, and are careful not to leave a trail of evidence which could be used against them.

In the course of investigating the adoption trade, CNA spoke to two other baby brokers in the capital. Both of them said they operate in the same slum as Joyce, where unwanted pregnancies are common and paid adoption is widespread. One of the brokers has arranged three illegal transactions so far. The other has organised two. According to them, sellers tend to be young Filipino women who work at bars and do not want to raise their newborn babies.

“Most of the time, we find these people in slum areas. They don’t want the pregnancy in the first place. So, the moment the child is born, they try to dispose of it. They try to sell it for money,” said Ronald Aguto, chief of the International Operations Division of the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI).

Last year, he said his agency examined about 10 cases of commercial adoption of children. The case numbers have been "steady" in recent years, but that is because the NBI does not have a unit dedicated to tackling the crime.

Aguto said that if there were investigators dedicated to this kind of crime, the case numbers would probably shoot up.

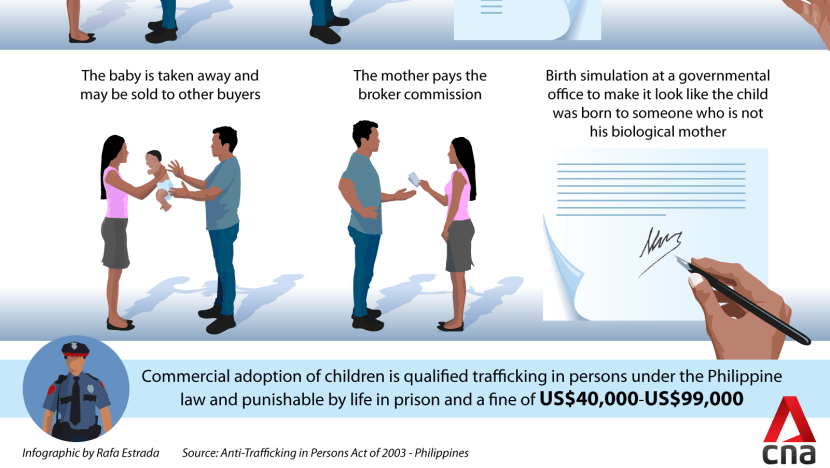

In the Philippines, the NBI is at the forefront of a national effort to eradicate commercial adoption of children. The practice is legally defined as trafficking in persons and it is punishable by life in prison and a fine of US$40,000-US$99,000.

“We have the adoption law. So, the moment you divert from that law, the moment you do it the ‘shortcut’ way - you receive money from it, you profit from it - it becomes child trafficking,” Aguto said.

ADOPTION VS CHILD TRAFFICKING

Despite the harsh penalties, commercial adoption of children continues to exist in the Philippines. According to the NBI, transactions mostly take place in Metro Manila, where payment is made in cash, face-to-face. Some infants are brought from rural areas in the provinces and hand-delivered to buyers in the metropolis, Aguto told CNA.

Based on his experience, traffickers tend to operate in a small group of 2-3 persons, including two parents and a baby broker. However, there is no official record that reflects the actual scale of the trade in the Philippines, given its clandestine nature.

“Trafficking in children is a global problem affecting large numbers of children. Some estimates have as many as 1.2 million children being trafficked every year,” said the United Nations Children’s Funds (UNICEF).

High demand for newborn children means orders keep coming in irrespective of whether there is a willing pregnant woman. Prospective buyers usually come to brokers with requests such as preferred gender, age and appearance. Then they will wait for the search to complete. If Joyce cannot find the right one, she said, her business will slow down.

“But some people would tell me ‘This baby isn’t really going to be mine. I’m also giving it away to someone else’,” she told CNA.

“They aren’t the ones adopting the babies; they just get them. Usually, we’d find out that babies bought from us are off to other places. How much did they get paid? They said 80,000 pesos (US$1,600)."

Before an infant gets sold, Joyce added, some buyers also cover prenatal care expenses, costs of childbirth and transport for the mother-to-be, which normally begins when they are 7-8 months pregnant.

By this time, she said, both the seller and buyer will already have a better idea about the child’s health and the risk of miscarriage would be low. The final payment only takes place after the delivery and, sometimes, the infant would be whisked off right after it was born.

“The moment I cut the umbilical cord, the adoptive parents who have brought baby clothes with them would wrap the baby and take it away,” Joyce said. “For me, this isn’t adoption. What they’re doing is selling. They’re selling the kid.”

IT'S ALL ABOUT MONEY

Illegal adoption of children in the Philippines often involves simulation of birth records. It refers to the fictitious registration of birth that makes it look like a child was born to a person who is not his biological mother.

“The baby is given to you when it’s days old. When you register the child, you can actually say ‘Oh the child is mine’ and put your name there. It’s the easiest way whereby illegal adoption can be practised,” said Gwendolyn Pimentel-Gana from the Commission on Human Rights - a governmental agency that investigates human rights violations against vulnerable groups in the Philippines.

Despite the adoption law, she added, “there are cracks in the system, so many factors that would compel a parent to traffic their children by selling them to couples who don’t want to go through the legal process.”

According to UNICEF, there is a demand for trafficked children as cheap labour or for sexual exploitation. Although there is no case linking illegal adoption to such crimes in the Philippines, Aguto said "it’s a big possibility because otherwise, they’ll go through the legal process to adopt somebody".

However, legal adoption can be a lengthy affair that involves both administrative and judicial processes. As for biological parents who want to give up their child for adoption, they have to meet certain requirements set out by the Department of Social Welfare and Development.

But while the legal channels can provide them with social assistance, they do not offer any financial gain. So for those who are desperate for money, giving away their child for free is not an option.

“They don’t think so much about going to the centre. It’s like they don’t have time for it. All of their time is spent on other things. Then what comes out of it just gets sold off - the babies they’ve created - because they can’t raise them,” Joyce said.

“Sometimes I think ‘Why do these mothers exist?’. They don’t even think. But I can’t decide for them. I’m not a mother and I also need money. Money rules. Whichever angle you look at, it’s all about money.”

This is the first in CNA's three-part series 'Babies for Sale'. In the second part, we track down a mother who wants to sell her two-month-old baby and talk to other key players in the trade.