The 26-year-old who’s giving hope to India’s acid attack victims

Fashion graduate Ria Sharma chose a different life to help acid attack victims, and opened India’s first rehab clinic for them. The series Champions for Change highlights individuals who are effecting change in their communities.

NEW DELHI: She was a “dumb little 21-year-old” with a privileged upbringing when she walked into a hospital and encountered a sight unlike any she had seen: “Flesh on the floor, blood on the walls, syringes everywhere”.

“There were about 20 beds, but there were, like, 20 bodies on the floor as well … It was literally what horror movies are inspired by,” recounts Ms Ria Sharma.

She was visiting a burns ward in India to make a documentary about acid attack survivors for a university project. But in that moment, she knew that her project was not going to make any difference in the victims’ lives.

The next day, she abandoned the idea for the documentary; instead, she registered a non-governmental organisation to support such victims, thus setting out on a different course of life from the one she knew surrounded by domestic helpers and chauffeurs.

She has since opened India’s first rehabilitation clinic for acid attack survivors, raising funds for their treatment and setting up a job portal to help them move on in life. Today, the 26-year-old is a global voice for these victims.

She has won the British Council’s Social Impact award in India, the India Today Woman in Public Service award and became the first Indian to receive a United Nations’ Goalkeepers Global Goals award, for outstanding activists making an impact in people’s lives.

This young woman is one of Channel NewsAsia’s Champions for Change, a series marking the channel’s 20th anniversary this year by celebrating 20 individuals whose imagination, talents and efforts have uplifted communities across Asia.

They include a woman in Myanmar who started a restaurant providing street children with education, food and shelter, a Korean graduate inventing devices for the blind, such as a braille smartwatch, and a Cambodian engineer building robots to defuse landmines.

SHE WAS A ‘NAUGHTY, SPOILT BRAT’

For Ms Sharma, her work with acid attack victims is a contrast to the way she grew up – in a household where she was expected to do little.

“Till I got to university, I didn’t even know where the trash went,” she admits. “I’d just throw something in the dustbin in my house, and I wouldn’t know what happened after that. My flatmates were like, ‘Are you serious?’”

Even her father Raman Sharma says: “Ria was a naughty, spoilt brat.”

As a fashion undergraduate in the United Kingdom, she was once warned by a lecturer about her bad grades. So they discussed issues that would interest her, and one was the 2012 Delhi gang rape case.

That was when, as she was researching violence against women in India, she stumbled across a picture of a disfigured woman, a victim of an acid attack.

“I couldn’t comprehend how the simple motion of throwing a cup of liquid on someone could cause that sort of lasting damage. And it sent me on this mad obsession to try and understand how this could happen,” she says.

Before the hospital visit that really changed her perspective, the working title of her documentary project was Make Love Not Scars. That became the name of the NGO she founded in Delhi in 2014.

A SAFE HOUSE FOR SURVIVORS

Acid attacks are a problem worldwide, from South-East Asia to the Middle East to Africa, according to London-based charity Acid Survivors Trust International.

But India has one of the highest rates of attacks: Some 250 to 300 cases are reported annually. And with assaults often going unreported, some say it could be several times higher.

Ms Sharma’s NGO works on all aspects of rehabilitation for survivors and has helped over 100 victims so far. It runs a halfway home where they can recover from their surgeries and also heal by relating to one another.

There is no other halfway home in India for such victims, which is why those who have nowhere to go might continue to live with their abusers, says the NGO’s chief executive officer Tania Singh.

“So this centre acts as a safe space, and whenever survivors are attacked by their own family member, they come here,” she adds.

Besides providing shelter, the NGO is working to create acceptance for their girls. “We help survivors out legally, medically, or with funding or to set up their own businesses,” says Ms Sharma.

“We have English classes and computer classes in order to equip survivors with vocational training that’ll eventually help them be contributing members of society.”

The rehabilitation centre has also evolved to make the survivors independent, give them a sense of purpose and help society understand that they should not be treated differently, as they want jobs for the same reasons that others want jobs.

Ms Sharma knows, however, that changing society’s mindset will take time. The NGO’s job portal lets prospective employers browse around to hire victims based on their curriculum vitae. But just two years ago, the discrimination was “very offensive” and “hurtful”.

“Now it’s more subtle. (Previously) a survivor would come back from an interview and say, ‘They told me straight up that they didn’t want to hire me because of the way that I look,’” she says.

“And now it’s ‘we’ll get back to you’, but not really ever getting back.”

FIGHTING THE SYSTEM

There is also the issue of the authorities not doing enough to control the sale of acid. India’s Supreme Court ordered sale regulations in 2013, but states are not implementing them, she laments.

Acid is readily available in shops across the country, as it is commonly used for cleaning purposes. A litre of it could cost 100 rupees (S$2).

Ms Sharma’s NGO has petitioned the federal government to ban the open sale of acid and to implement the Poisons Act and the rules more strictly.

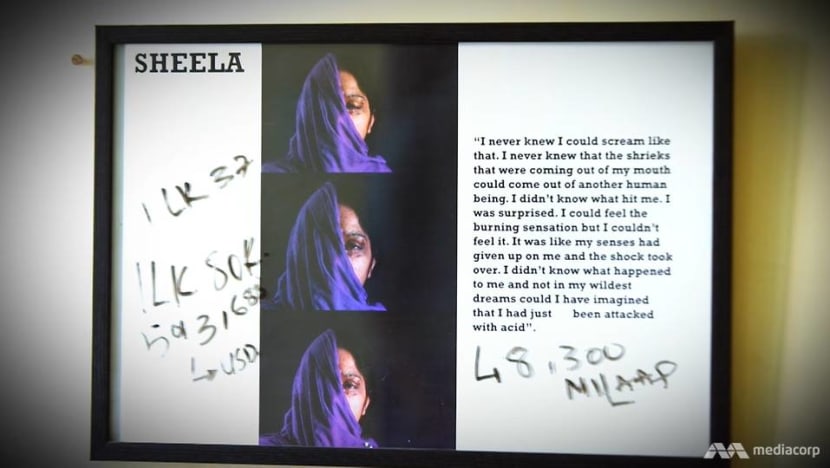

An acid attack, she says, is the worst crime to commit against someone because “not only are you stealing their identity from them, it’s a crime that stays with (them) for the rest of (their) lives”.

And it goes beyond disfigurement. “Survivors have to go for surgeries for years … till they can achieve some sort of normal. The psychological and social aspects of it make it one of the most horrific things you can ever do.”

Lawyer Kumar Vaibhaw points out that although an acid attacker faces not less than 10 years in jail to a maximum life imprisonment, India’s justice system is slow and can take “10 to 12 years” to resolve a case.

By that time, the acid attack victim loses her confidence and sometimes even the will to follow up with the case. And that’s why there are cases that cannot be brought to their logical conclusion,” he says.

The law also sets a time frame for compensating survivors after the incident, and they are entitled to free treatment in government and private hospitals. “The problem is that there’s absolutely no implementation of these laws,” says Ms Sharma.

The victims’ families often have to sell their possessions instead, so Make Love Not Scars tries to get them the medical care they need.

Mdm Zakira is one of those the NGO has been helping after her suspicious husband, who thought she was having an affair, threw acid on her face when she was asleep.

“I had smoke coming out of my face,” she recounts. “I never thought acid can ruin anyone’s face so badly.

“It’s hard to think of how I used to look. When I met my children, they said, ‘This isn’t our mother.’ They were scared. They said, ‘Our mother looks like a ghost.’”

NOT SO SELF-CENTRED

Fighting the system is one battle. Running an NGO also brings its own challenges, especially in India, which Ms Singh points out has many problems and many NGOs.

“So we’re trying to survive in a highly competitive market with the domestic funds available, which are very, very limited. And that actually halts our expansion,” she says.

She and Ms Sharma are of the same age, both with no prior job experience, and they “sometimes struggle to make decisions”.

“We don’t have the knowledge of how a big organisation grows, and sometimes we feel as if it's getting bigger than we are,” she adds.

Nonetheless, Ms Sharma, who has benefited personally from helping the victims, is trying to look ahead.

“The survivors have given me more than I could ever give them,” she adds. “They saved me from a life of being self-centred and a life of being superficial.”

Her father remains hopeful she will find a paying job, as she does not draw a salary now.

“I’d like to see this crime (acid attacks) really dropping in frequency, and then she takes a back seat. And then maybe Ria will finally find a job,” he says half-jokingly.

But Ms Sharma maintains that will not happen, as she feels deeply for the women with whom she works. “You don't just leave something that you started … And you don't abandon the people whom you love,” she says.

“When someone is attacked with acid, they believe that they’ll live the rest of their lives as a living corpse … Make Love Not Scars exists to show them that they're more than just a corpse and that they’re butterflies.”

Catch the first episode of Champions for Change on Wednesday, Jan 2, at 9pm, or watch it here.