The Big Read: The 'invisible' people in a class-conscious society

A security guard in Singapore. (Photo: Gaya Chandramohan/CNA)

SINGAPORE: Madam Chua Oi Lin, 64, tries to make herself inconspicuous when she is working.

At 7am every work day, she begins cleaning the toilets and common corridors on five floors of the 15-storey Tan Boon Liat Building, before making her exit by 10am when the office workers and shoppers start streaming in.

At 1pm, when most of the occupants are out for lunch, the cleaner would re-emerge for another round of cleaning to freshen up the same areas before calling it a day at 4pm.

Madam Chua said she thinks that being “invisible” has its merits, even though it makes her day for someone to simply greet her or acknowledge her presence, never mind not thanking her for her efforts.

More often than not, however, crossing the paths of fellow human beings bring about unwelcomed consequences: People might complain to her superiors when they see her resting in between her cleaning shifts. Then, there are the nasty encounters, said Mdm Chua, who is married to a 78-year-old retiree.

Once, she accidentally sprayed some tap water on a man in one of the toilets, and he cursed her mother in Hokkien in retaliation.

While she has resigned herself to the fact that many people look down on her for doing a “dirty job”, the man’s remarks angered her so much that she gave him a piece of her mind.

“I told him not to scold me bad words as I am here to work, not to have my mother insulted by him,” said the cleaner who is paid S$1,200 a month and still cares for her mother who is in her 80s.

The issue of low-wage workers like Madam Chua, who often end up as “invisible” in their workplaces — people simply walk past them without greeting or talking to them, and they are not shown the respect they deserve or treated with dignity — was highlighted recently amid the ongoing national conversations on social mobility and inequality in Singapore.

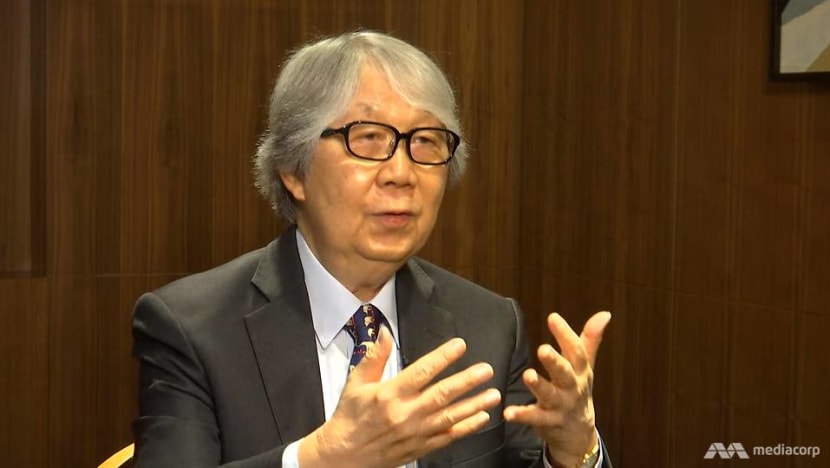

At a dialogue session with Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam late last month, Ambassador-at-large Tommy Koh said the issue is not about these people doing their jobs with dignity, but about the way “the elite” treats them.

Prof Koh said:

I would say in Singapore, the elite does not show respect for people who work as cleaners, gardeners, petrol station attendants, security personnel. One of the problems in Singapore is that these low-wage workers are treated as invisible people.

He was responding to Mr Tharman’s suggestion that there should be more focus in helping Singaporeans in their mid-50s and 60s to “work for as long as they wish, to work with dignity, to earn a decent pay”.

Mr Tharman had noted that 60 per cent of working Singaporeans aged 55 and above, with no more than secondary school education, had ended up at the lower end of the “escalator” of social mobility.

As for Prof Koh’s “elite” comment, Mr Tharman said that it is not only the elite who shows little respect for the ordinary blue-collar workers, describing such an attitude as “part of our social culture”.

“We inherited a combination of British institutions and an East Asian culture, both of which are quite hierarchical, both of which tended to look down on ordinary manual labour,” said Mr Tharman in the session held ahead of a conference to mark the 30th anniversary of policy research think-tank Institute of Policy Studies (IPS).

In an email interview, Prof Koh continued to view the issue as one involving members of the elite, which were once part of “a classless society” and now live in “a class-conscious society”.

The elitist attitude rears its ugly head when they “do not greet (those who do low-paying jobs) or acknowledge their presence”, he said, relating an encounter on Tuesday (Nov 6) where one of three men who washed his car at a petrol service station thanked Prof Koh’s wife for speaking to him.

“The poor people of Singapore need better pay and respect from the elite,” Prof Koh stressed.

LIFTING THE CLOAK OF INVISIBILITY

Long used to being given the cold shoulder, it did not take much coaxing for these “invisible” people to lay bare their suppressed frustrations and unaddressed hurt.

A 59-year-old toilet attendant at Marina Bay Sands (MBS) shared that she often greets guests with a friendly “good morning” or “good evening”, but most would just ignore her and carry on with their business.

The woman, who wanted to be known only as Madam Lim, said: “If you work this kind of job, people don’t look up to you. They see that you are illiterate and uneducated, they don’t really see much value in engaging with you.”

Toilet janitor Madam Goh – a 76-year-old who made the news in August due to a spat over five-cent coins – lamented that people seldom consider the point of view of workers like her.

In the incident, the janitor at Block 79 Circuit Road hawker centre chided a woman who had paid the toilet’s 10-cent entrance fee in two five-cent coins.

News of Mdm Goh’s disgruntlement quickly spread after the woman’s niece posted the janitor’s photo on Facebook. But Mdm Goh pointed out that few would have known that she had only started refusing the coins after years of getting her own five-cent coins rejected by members of the public when she returned them as change.

“Look, I still got so many,” said the janitor of more than 30 years who declined to give her full name due to the “negative press” she had received, flashing her quarter-full canister of five-cent coins.

On a daily basis, Mdm Goh would also encounter two to three fee evaders, directly affecting her earnings since she only takes home the amount she collects, sharing the money – S$20 on average – with her 61-year-old nephew who takes the night shift.

Still, Mdm Goh considers herself fortunate, noting that tray and plate collectors at food courts have it worse, since they need to move about a lot more and often face customers, which raises the chances of conflict.

Freelancer Euphemia Lee — who witnessed a woman scolding a food court cleaner who had prematurely cleared her plate at Jem mall in 2016 — said she had become more aware of how cleaners were treated around her since.

“I have seen this happen almost on a day-to-day basis, be it (customer's rebuke) verbal or non-verbal. Looks of disgust towards staff are not uncommon,” said the 32-year-old.

The 2016 incident made the headlines after a video of the customer's tirade against the deaf and mute cleaner went viral on Facebook. The customer later apologised for her actions.

Although it has been more than two years since the incident, Ms Lee said she remained disturbed by the customer's initial behaviour and remarks. “(They) showed a lack of empathy towards another human being,” she said.

Ms Nur Shakylla Nadhra, a sub-editor at a research company, notices that some of her colleagues do not acknowledge the cleaners when they clear the trash cans under their office desks. “I understand that you are busy, but there is not even a glance. It only takes a few seconds (to say thank you)," said the 27-year-old.

Another group of “invisible people” are security guards who have to grapple with rude behaviour and have unkind remarks thrown at them.

Mr Surjeet Singh, a security guard of 20 years, said he had been called names such as “dog”, “idiot” and “bloody fool”, when trying to get people to comply with the rules of the premises they are in.

“It really lowered my morale ... I feel very disturbed and it can affect you emotionally, where you go home still thinking why the man said that to you,” said Mr Singh, 58, who earns S$1,500 a month.

Mr Singh’s boss, Ademco Security Group managing director Toby Koh, cited the case of a security officer at a condominium who was told to clean up the mess after a resident’s child had vomited.

There have also been occasions when parents would tell their children to “study hard, if not, you may become a security guard” even while an officer is standing nearby, he said.

For office cleaner Loke Yoke Chee, his most unforgettable day was the time when a high-ranking American employee at Royal Bank of Scotland at One Raffles Quay took him and his fellow workers out to lunch at a Vietnamese restaurant to celebrate Christmas in 2010.

“That was the first time in my life somebody (of a higher status) invited me for lunch,” said the 60-year-old who depleted his savings while fighting lymphoma, a cancer of the blood.

Except for that Christmas lunch, Mr Loke has spent most of his 20 years as a cleaner trying to keep out of other people’s way — and sight — as far as possible to avoid being an “ear sore” while he is vacuuming the floor, or a “distraction” while wiping office and meeting room tables when bank employees start filing in from 9am.

He would then proceed to clear the rubbish bins and tidy up the pantry areas before lunchtime.

Mr Loke, who now mainly tends to the mall area of OUE Downtown, has learnt to take it in his stride and not get “too bothered” when he meets “some people with higher education who look down on us”.

He would often tell himself that

I come here just to earn a living.

WHAT CONSTITUTES A LIVING WAGE?

Despite the cold-shoulder treatment that they often get from members of the public, those interviewed said such dismissive attitudes are the least of their concerns. Instead, they are more concerned about keeping their jobs.

For MBS cleaner Madam Lim, her monthly pay of S$1,500 goes towards her immediate living expenses.

While her daughter, who is in her 20s, had just graduated with an accounting degree from a private university, Mdm Lim said: “I can’t rely on her because I didn’t support her university education. We had no money. She put herself in university through her own means, by taking on a part-time job.”

Mdm Lim’s son, in his 30s, is a watch salesman while her husband holds an unstable job slaughtering ducks in Jurong.

At the IPS dialogue, Prof Koh had asked what can be done to ensure that low-wage workers are “able to live in dignity and material sufficiency”, adding that his own research had shown that there are between 100,000 and 140,000 households living in absolute poverty.

As for the portion of households living in relative poverty, he noted that his estimate is closer to 20 to 35 per cent, not 15 per cent as previously cited by Education Minister Ong Ye Kung.

In a subsequent Facebook post on Oct 27, Prof Koh described the income distribution of Singapore as a “moral disgrace”, in that it currently resembles the shape of a pear, whereas founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew had envisaged one that resembles the shape of an olive.

READ: Use the right lamp to light the way forward on inequality, a commentary

“Many of our working people do not earn a living wage and live in poverty”, he said, adding that the progressive wage model in force in three sectors – starting with the cleaning sector in September 2015, followed by the landscape and security sectors in 2016 – did not change the situation.

His comments fuelled a spirited debate on whether Singapore should have a minimum wage, which has been adopted in Japan (average of 848 yen or S$10.25 per hour), South Korea (7,530 won or S$9.20 per hour), Taiwan (NTS$140 or S$6.25 per hour) and Hong Kong (HK$34.50 or S$6.07 per hour).

Singapore’s chosen progressive wage model is meant to address wages in sectors that had stagnated due to widespread cheap sourcing and a limited scope for collective bargaining, as prices are locked in once contracts are signed, resulting in high turnover and labour shortages.

Currently, among cleaners engaged in the office and commercial areas, the minimum monthly wage for a general or indoor cleaner is S$1,120. Outdoor or healthcare cleaners should at least get S$1,320, and cleaners who are “multi-skilled” or able to operate machines should at least command S$1,520, while supervisors get S$1,720.

For those working in food courts, coffee shops, hawker centres or restaurants, table-top cleaners should be getting at least S$1,220, while dishwashers or refuse collectors should get a minimum of S$1,320.

As a basic requirement, all cleaners will have to go for an eight-hour course called “Demonstrate understanding of the local cleaning industry environment”.

To move up the ranks, they can undergo training under the Singapore Workforce Skills Qualifications – a national credential system that trains, develops, assesses and certifies skill and competencies for the workforce.

National University of Singapore sociologist Tan Ern Ser sees the training courses as a possible solution for the “invisible people”, who largely come from the generation who grew up in the 50s or 60s with only primary, lower, or no education.

As an alternative to skills development, Asst Prof Namrata Chindarkar of Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy suggested that corporates may consider “senior internships”.

“(The approach that creates and identifies jobs where older generations can add value and which they also find meaningful and fulfilling) may potentially unlock ground-breaking ideas on how services and technology can truly benefit the elderly,” she said.

Assoc Prof Tan also pointed out that society could redesign jobs to cater to seniors, promote health lifestyle and active ageing, provide income supplements and subsidised healthcare and housing, and enable their children to play their part in supporting the elderly.

For example, there are schemes for low-wage earners, such as the Workfare Income Supplement (WIS) which helps workers earning a gross monthly income of not more than S$2,000 by giving them additional cash payouts and Central Provident Fund (CPF) contributions.

The WIS hands out a maximum of S$3,600 to a worker aged 60 and above, of which 40 per cent would be paid in cash and the rest going into his or her CPF account.

Younger workers get less, with those aged between 35 and 44 getting up to S$1,500, those between 45 and 54 getting up to S$2,200 and those between 55 to 59 getting up to S$2,900.

Last year, 366,000 workers came under the scheme, with a quarter of them estimated to be working in the cleaning, security and landscape sectors, said National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) Assistant Secretary-General and Member of Parliament Zainal Sapari.

While helpful, the maximum cash payout of S$1,440 a year, which translates to S$120 a month, does not get the workers out of their vicious circle, said older low-wage workers who were interviewed.

A few were also sceptical about upgrading their skills at their age, especially when their trainer in the basic course could only speak English while they are native Hokkien speakers.

A cleaner with Marvel Clean, 53-year-old Daud Yusof, who started working in the sector eight years ago with a monthly salary of S$950 at another company, and now earns S$1,600, is yearning for a bonus structure to reward the hardworking workers.

“I work even when I am sick. I have never gone to see a doctor (and taken MC) … because money is very important (to survive in Singapore),” added the bachelor.

Apart from the workers themselves, other Singaporeans interviewed also felt that more should be done – by society as a whole – to take better care of this group.

READ: The trouble with helping disadvantaged kids is you don’t know where to start, a commentary

The issue for lawyer Walter Silvester, 42, is not that there is something wrong about the low-wage workers, but “something is wrong about the society” that does not feel it has an obligation to uplift the people who have been disadvantaged throughout their working lives.

“A lot of them shouldn’t be doing what they are doing at this age. We have to pay the price, so if we are willing to pay higher prices for the services they provided, it will go some way to solving their problems,” he said, noting that the progressive wage model is not effective.

“These people are earning S$1,000, S$1,000-odd per month. You can’t do anything (with that) in Singapore,” he added.

Mr Silvester felt that the workers should be getting at least S$1,600 or S$1,800 a month to keep up with the “standard of living” here.

He said: “Over the last 10 to 15 years, there have been a lot of changes, a lot of progress in certain sectors of society, there has been a lot less in others. We can’t just move on, and then a bunch of us are having a good salary, making money, and these people left behind aren’t given the same opportunities.

“The increased standard of living? They (low-wage workers) have nothing to do with it. They are not gaining from it. We should look after them because as a society, we decided to go on this path, but we are not bringing them along with us.”

To restore the balance between the disparate groups, Mr Silvester added:

I don’t mind being taxed more if it is going towards things that we need to do, things that we need to take responsibility for.

IMPROVING WORKING CONDITIONS

The contentious issue of wages aside, the rest quarters for members of this “invisible tribe” have also attracted the attention of some Singaporeans. They noted that the quarters are often set up in a bad location, such as beside a rubbish dump.

Employers said that they are at the mercy of service buyers or customers – building operators and tenants – who will not hesitate to switch to another contractor if they raise the issue about the area allocated as rest quarters.

Mr Sapari, who created a stir earlier this year after pointing out that some vulnerable low-income earners were working like “slaves”, could empathise with the employers in this instance.

READ: Zainal Sapari's commentary, Singapore must do more to guard against 'slavery of the poor'

Last month, while he was trying to help a group of cleaners get a proper rest area by raising the matter with the authorities, the managing agent terminated its contract with the cleaners’ firm, citing the company’s non-performance.

“In the cleaning industry, it is very easy for service buyers to find reasons for non-performance, whether valid or not,” Mr Sapari said.

“I personally feel that the managing agent terminated the contract because they were unhappy for being told off and instructed by the ministry officers to provide a rest and storage area for the cleaners.”

Such a proper resting area does not even have to be a room, he added, pointing out that it could be carved out of a small area with proper furniture and ventilation for the workers.

Chief executive officer of Bizlink Centre, Mr Alvin Lim, suggested that a proper resting area could be made a requirement in the building code, similar to how it was written into law for every building to incorporate a fire command centre.

A former teaching staff at a private school, who declined to be named, said that at one of its campuses, he noticed that the cleaners’ quarters are beside the rubbish chute, where the low-wage workers would have their meals.

“These are obviously not ideal conditions to work in,” he said. Some of these allocated quarters are also said to be too small.

Madam Lin Yi Zhu, 72, who works as a cleaner at Botanic Gardens MRT station, said she wears two layers of clothes on the job – her uniform with her own blouse underneath – as she does not have a cabinet where she can store her belongings properly. There is only a storeroom where the broom and dustpan are kept.

Mdm Chua, the cleaner at Tan Boon Liat Building which hires eight cleaners, had over the five years she worked there “built” her own resting area at the staircase landing.

It is located just above the cleaners’ designated office located in a tiny room under the stairwell, which could not accommodate all eight workers at the same time.

Her makeshift quarters was set up using scraps she had picked up while cleaning, including a wooden plank as a bed and a cardboard box as a dining table.

Mdm Chua’s employer, Benchmark Cleaning Services director Jason Tan Tze Li, said he was not even given a big enough space to keep the vacuum cleaning machine at one office his firm cleans after it was renovated, much less a dedicated corner for his cleaners.

As an employer, Mr Tan, 37, also finds it important to educate service buyers who are asking for younger cleaners who can speak English, since they are not necessarily his best workers.

“Younger folks might decide to show up one day and not show up another day. Older folks (in their 50s and 60s) are good. They are more serious, have a greater sense of responsibility, and put their heart and soul into doing a good job,” he said.

As for speaking English, he said it is not hard for the older folks to pick up terms like “coffee” or “tea”, which are almost all that they need to know to do a good job.

Mr Tan also called for others to show more empathy for cleaners who cannot be expected to work for eight hours non-stop.

“All of us need to give and take. If the morning is busy, afternoon, they should rest a bit more, it is okay,” he said. “If everyone goes by the book, there will be no end to nit-picking.”

Agreeing, Cyber Security Agency of Singapore consultant Matthew Loong, 34, said: “If employees are entitled to their break time at the pantry, the cleaner should also be entitled to his or her break time at the pantry.”

Treating low-wage cleaners with dignity could also come in the form of taking their feedback seriously, said a former full-time National Serviceman who regretted not pursuing a complaint by a cleaner auntie at his camp.

The soldiers are expected to clean up after themselves, but the cleaner in her 60s had to clean up after the men when they returned from field training with their muddy boots, said the man, now in his 30s, who declined to be named.

“She confided in me, expecting me to forward the feedback, which I did, but no one did anything about it,” he said, adding that he let the matter slide even though she continued to complain over having to clean up after the men.

Looking back, he felt that he had been irresponsible by being indifferent towards the elderly cleaner. “I was not nasty to her, but I also did not regard her as well as my colleagues in the office,” he said.