Ivory, rifles and opium: NLB's rare collection reveals Singapore's 19th-century shopping list

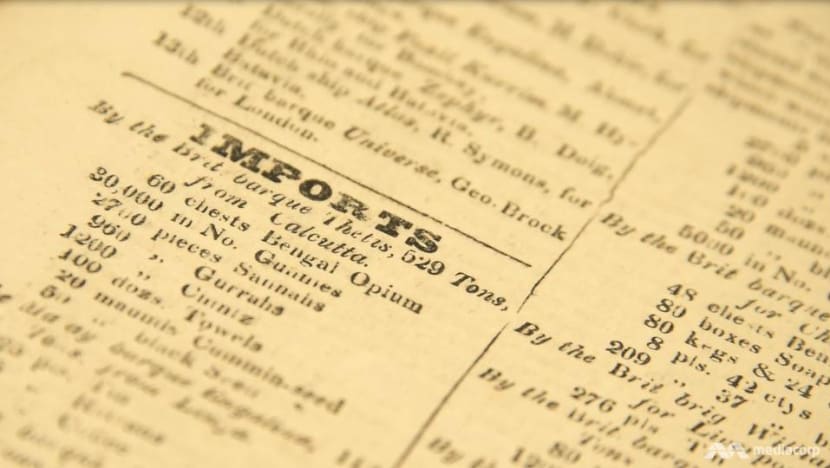

Singapore used to import towels, gurrahs (coarse Indian muslin) and opium from Calcutta. (Photo: Hanidah Amin)

SINGAPORE: It’s hard to imagine Singapore as a scene straight out of an 19th-century pirate movie: A murky port where swashbuckling sailors traded in arms, drugs and animal parts.

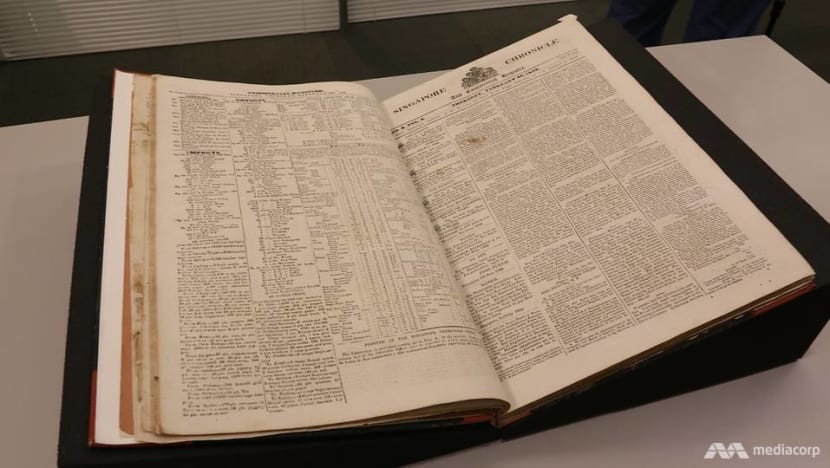

But 1834 editions of the Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register – the country’s first newspaper established a decade earlier – show just that.

The newspaper focused on trade news, with ship arrivals and import inventories dominating its densely filled pages.

There’s the usual rattan and rice from Palembang, and soap and butter from Batavia (present-day Jakarta). Then there’s the unusual: Elephant teeth from Siam, rifles from Liverpool and opium from Calcutta.

While these were valuable commodities those days – ivory was used to make jewelry and religious objects, while rifles were used to hunt game – the opium trade is far more intertwined with Singapore’s past.

“Why is this newspaper so important?” asked senior librarian Gracie Lee, who works in the National Library Board's (NLB) rare materials collection where original editions of the Singapore Chronicle are kept.

“I think we often hear that newspapers are like the first rough drafts of history. This contains a treasure trove of historical information on early Singapore.”

READ: Finding yourself - and your roots - in the National Archives

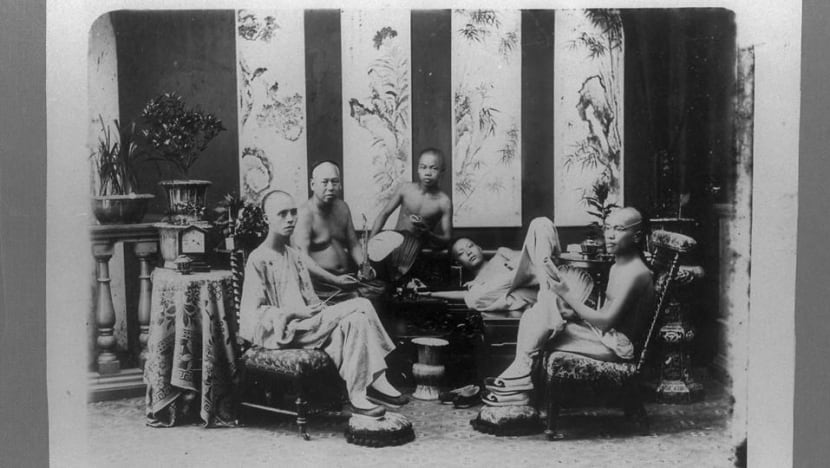

Ms Lee said opium was cultivated in British India, rolled into balls and stored in chests, then brought to Singapore to be processed into different grades. Chinese coolies in Singapore usually got the poorest quality, she added.

With the establishment of Singapore as a free port, the opium tax-farming system was introduced as one way to raise revenue, according to NLB’s infopedia on Singapore. Shopkeepers would also recover ash from smoked opium and sell it at cheaper prices.

The colonial government passed the Opium Regulation in 1830, and until 1910, the annual revenue from opium accounted for an average of 30 to 55 per cent of its total income.

But the Singapore Chronicle is just one of some 15,000 items in the rare collection that tell different stories of Singapore's history. It contains significant materials on Singapore and the region dating as far back as the 15th century.

“These materials are inherited from the Raffles Library collection, but also recent acquisitions and donations,” Ms Lee, 44, told CNA, referring to Singapore’s first public library which opened in 1845 under a different name.

“So they would be things like travel accounts, European travel writings on Southeast Asia, remittance letters or maps. Yeah, all sorts of things that you can imagine.”

As the name of the collection suggests, these things also have some degree of rarity.

The oldest artefact in the collection is a 1478 map of Southeast Asia based on work by the famed astronomer and geographer Claudius Ptolemy.

And only three other libraries in the world are believed to hold early issues of the Singapore Chronicle in original hard copies: The British Library, Leiden University Libraries and the National Library of the Netherlands.

“John Crawfurd believed that having such a paper would increase the respectability of Singapore as a port,” Ms Lee explained, referring to the newspaper’s endorser who succeeded William Farquhar as the second British resident of Singapore.

“This was meant to be a mercantile newspaper to facilitate trade,” she added, extremely reluctant to turn its yellowed pages to protect it.

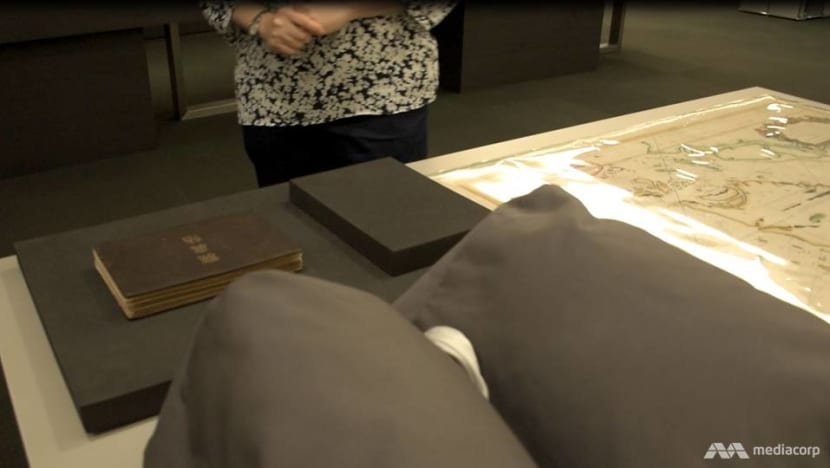

The bound collection of the newspaper looked more like a fragile tome, with its hard cover, narrow columns and dozens of large portrait pages. It rested on a piece of archival black foam designed to support and not contaminate such treasures.

THE RARE GALLERY

While the rare gallery isn't exactly a tomb of lost treasures – it's on level 13 of the National Library Building in Bugis, guarded by a lone no-entry sign and two layers of locked doors – access is still restricted.

Public tours are conducted only once a month. Larger exhibitions are held on level 10 once a year. And Ms Lee might as well be your modern-day Indiana Jones.

She might be petite, with a bob cut and kind eyes, but beneath this veneer lies a somewhat more steely side to her personality – as a keeper of some of the most valuable artefacts from Singapore's history.

When asked where exactly the original items were kept, she replied jokingly: “If I tell you, I’ll have to kill you.”

CNA was given a private tour on a quiet weekday morning in early August, when there was barely a soul around. The almost eerie silence was broken when Ms Lee beeped open both layers of locked doors.

The rare gallery is no bigger than a children’s section in one of Singapore’s public libraries. But unlike the children's section, it is gloomy with dark colours and dim lighting. The air is stale and sterile, with the room being kept at a constant cool temperature.

Light, heat and humidity can destroy the rare items, Ms Lee explained.

In one corner hung Ptolemy’s map, encased in a glass panel fitted with small lights and a hygrometer measuring humidity. But this was just a replica.

The originals that could be shown were laid out on three separate tables, and Ms Lee proceeded to tell their stories.

DESTINED TO BE A TRADING HUB

Even before the Singapore Chronicle and the arrival of the British in 1819, there is proof in the rare gallery that Singapore was already slated as a strategic gateway for ships travelling from the West to East.

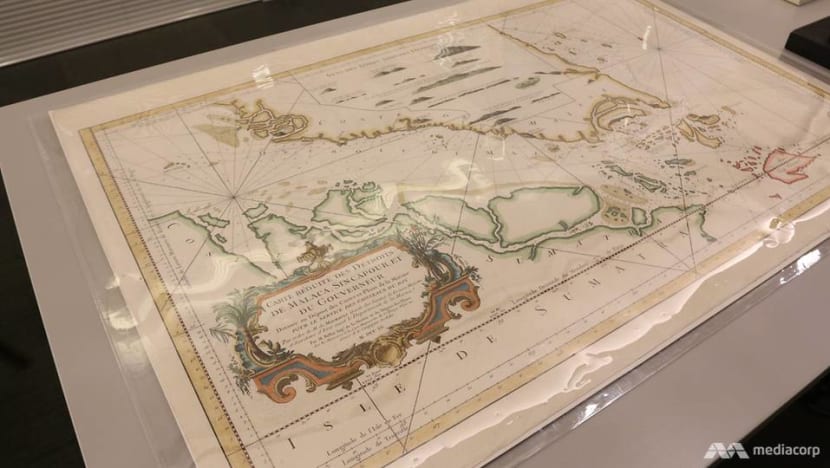

A 1755 hydrographic chart, by the prominent 18th-century French mapmaker Bellin, depicted three important sea passages around Singapore linking the Indian Ocean and South China Sea: The Singapore Straits, New Straits and Governor’s Straits.

Ms Lee said the map is one of the few to describe Singapore by its local Malay name Pulau Panjang, which means Long Island. It also shows the navigational route ships would take along the Malacca and Singapore Straits.

While the map was detailed and intricate – it even had small numbers indicating the depths of waters around Singapore – it didn’t exactly get the geography right. Singapore is shaped more like a banana instead of the four-sided island commonly seen today.

Ms Lee offered an explanation: “Because this is a hydrographic chart, the importance is really how to safely navigate the waters, and not an accurate representation of the shape of the island.”

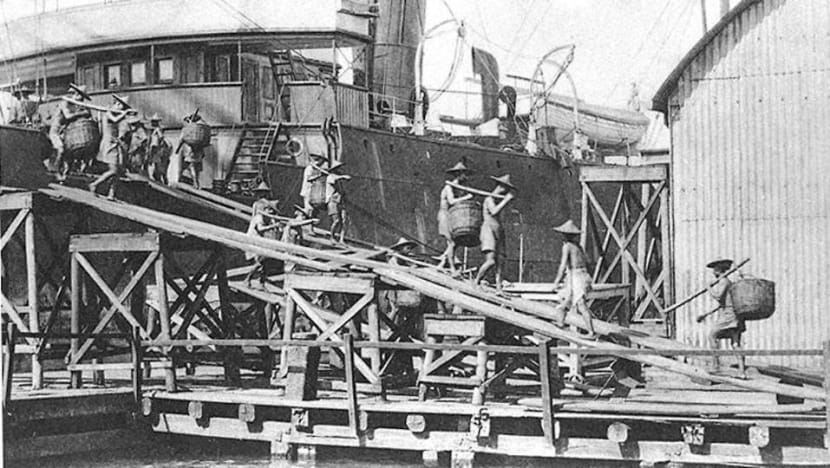

COAL COOLIES

On a more micro level, another item showed how Singapore was trying to solidify its status as a trading hub, with the opening of the Suez Canal creating a much shorter route for ships travelling from Europe to Asia.

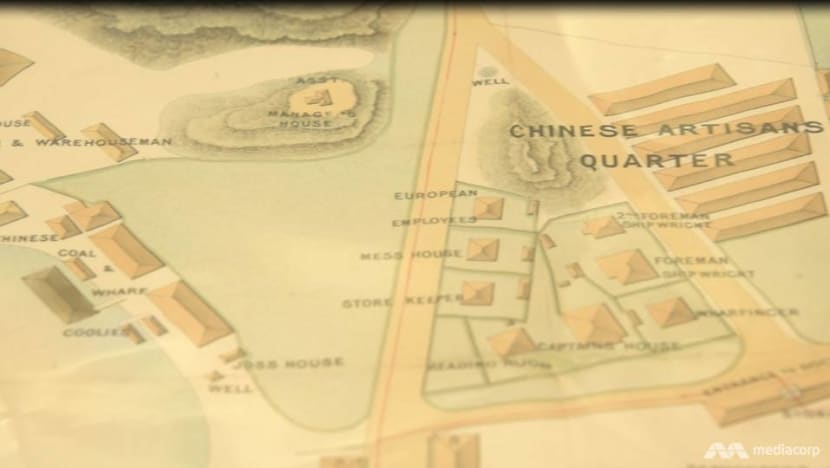

An 1878 plan by the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company showed an additional dock being constructed to support an increased demand for shipping services like repairs, Ms Lee said. This would later become today’s Albert Dock.

“The Tanjong Pagar dock was a major player in the development of Singapore's history as a port,” Ms Lee said, pointing to dozens of coal sheds in the plan.

“Singapore then was a major coaling station; steamships along voyages from the West to the East would call in Singapore and have their coal and water refilled.”

The plan indicated that the coal sheds, previously made of wood and attap, were constructed with materials like brick and mortar. This is because the plan was produced a year after a huge fire destroyed most of the coal.

“The fire was so major, it took two weeks for it to be brought under control,” Ms Lee added. “So, the company was galvanised to build these coal sheds with more durable materials.”

The plan also showed accommodation for the Chinese coolies who toiled through the day transporting coal. In 1874, there were about 300 coal coolies working for the company, with the Chinese forming a majority of its labour force.

“What’s interesting is nearby you see a joss house or Chinese temple to perhaps meet their spiritual and protection needs at the time,” Ms Lee stated.

PRESERVING RARE ITEMS

The rare and often fragile materials in the gallery also have their needs.

In the secret storage room, the temperature is kept at around 18 degrees Celsius and the humidity at about 55 per cent, lower than the levels in Singapore. There is no light.

“These are the factors that would accelerate the deterioration of paper-based materials,” Ms Lee explained. “Materials are also digitised so we can provide access while minimising direct handling of the original.”

Clean and dry hands are a must before any handling, although there's also a misconception that gloves are required. Gloves actually get in the way of proper handling, she added.

The items themselves are kept in plastic folders or paper boxes that protect the items during moving and storage, and allow for non-destructive pasting of important information like the title and barcode. Pens are a no-no in the room.

But these more expensive protective layers cannot be found in your neighbourhood bookshop. They are made from non-reactive materials like polyester or acid-free paper.

They are also customised for shape and size at the NLB’s supply centre in Changi South, which is also where rare items first brought in are fumigated to remove pests, repaired if there are structural damages and catalogued for online searches.

Some conservation techniques include removing dirt using goat hair brushes or Staedtler erasers, and repairing holes through infilling. This refers to filling the hole with a torn-off piece of similar thickness paper and applying wheat starch paste to make it stick.

MAKE IT NEW OR KEEP IT ANTIQUE?

But do conservators always have to do their best to restore an item to its former glory? National Archives of Singapore conservator Ong Fang Zheng, 30, said there's a "thin line" between restoration and conservation.

“A restorer will take a 200-year-old work and give it back to you like it’s 20 years old,” she said. “As a conservator, I will return it to you and it still looks 200 years old. But it’s structurally stable.”

Ms Ong acknowledged that conservators do restore items that are badly damaged, but said it’s ultimately a question of purpose.

“Restorers are more for the art market – things need to look good. For us, it’s about the historical, cultural aspect. And the authenticity and integrity of the object,” she added.

“Conservators are not magicians. Basically, all we’re doing is trying to retard the degradation process so our things can last centuries for future generations to enjoy.”

A THIRST FOR KNOWLEDGE

Back at NLB’s rare gallery, Ms Lee’s job is also to somewhat immortalise the rare items – by learning as much as possible about them and spreading the knowledge through tours, workshops and online blogs.

“As I work through and research a collection, I also begin to discover new aspects of Singapore history that I didn't know before,” she said.

“I enjoy meeting patrons or researchers who come to look at this collection because they will be able to share with me things that I've not discovered from these materials.”

The ever-curious Ms Lee has been with NLB for 13 years, previously working in the public libraries and also at the supply centre. About five years ago, an opportunity to work with the rare collection came up. She didn’t need to think twice.

“I've always had an interest in history, so being able to work with these original materials is really very fascinating,” she added, smiling. “It’s a different side of librarianship.”

Ms Lee works with a team to research and write about the rare items, as well as search for others that can be bought and added to the collection.

A committee will evaluate the item based on criteria like market availability and how it fits into the collection. Prices range widely – something found on eBay could be considered rare too.

“We might select from catalogues that we have received from dealers, or online alerts that we've set up,” Ms Lee said. “We also scour the Internet and look through auction sites to see if there are relevant materials we can acquire.”

LONG HOURS AND LANGUAGES

It's clear that Ms Lee loves her job. She even spoke at length about items that help prop up or hold down rare items during viewing. There are foam pieces in different shapes, a bean bag that looks like a pillow, and a long, thin weight which she fondly calls "snake".

But the job has its challenges as well.

Ms Lee works nine-and-a-half-hour shifts from Mondays to Fridays and sometimes on the weekends, when she conducts tours or helps customers with enquiries.

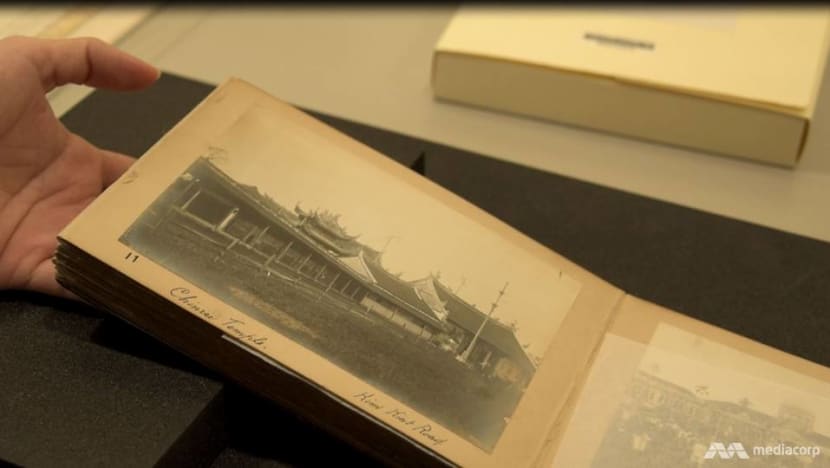

She might also not be able to fully understand the rare items, which might contain foreign languages like French or Portuguese. But she was quick to explain the Japanese characters on the cover of another rare item, an album containing photos of early 19th-century Singapore.

“Shashin, meaning photo album,” she said, noting that she has colleagues who can understand different languages.

Ms Lee is eager to learn and even more eager to teach. She's heartened when the 45-minute public tours become an hour or longer because “people are just so interested to find out new things about Singapore”.

“I think the universe of knowledge is very wide,” she stated. “So sometimes it's not possible to know everything, but I think we try our best.”