The Big Read: Searching for the good life, miles from home

SINGAPORE — From different countries, men and women, many equipped with precious little except for a strong will to eke out a living for themselves and improve the lives of their families back home, have come to Singapore to find work.

For some of these lower-skilled migrant workers, Singapore may not be what they imagined it to be. But for many, this city continues to offer them the elusive ticket to a better life. Scrimping and saving on their daily expenses, they try to send home as much money as they can — often at the expense of their own welfare.

Bangladeshi construction worker Mohammad Zahirul Islam, for example, gave up pursuing a degree and came to Singapore to earn money to help pay for his younger siblings’ university education. The aspiring poet carries a pen and paper with him as he toils under the sun.

“When anything comes into my mind, I write down. After finishing work and dinner at night, I will check and edit,” said Mr Mohammad Zahirul, whose biggest dream is to study English Literature in France where his brother is enrolled in medical school.

For all their hardships and sacrifices, the migrant workers long for the day when they can reunite with their loved ones and enjoy the fruits of their labour. Others have forged friendships and bonds with Singaporeans that are so strong that they hope to remain in Singapore for as long as they can.

This month, Singapore will commemorate Foreign Domestic Workers’ Day and International Migrants Day. For the Big Read this week, TODAY pays tribute to the foreign workers here and speak to some of them about their experiences, hopes and dreams.

ASPIRING POET INSPIRED BY DAILY TOILS

SINGAPORE — A construction worker by trade, Bangladeshi Mohammad Zahirul Islam sees pen and paper as his most handy tools.

The aspiring poet seeks inspiration from his daily toil under the hot sun at a Sembawang construction site, amid a longing for his wife and two daughters – aged three and 12 - back home.

Mr Mohd Zahirul, 37, left his hometown in Bangladesh eight years ago to work in the construction sector here. The eldest son of a family with seven children, he came here with hopes of supplementing his father’s meagre monthly income of about S$100 as a schoolteacher and in doing so, ensure his younger siblings get to pursue tertiary education and fulfil their dreams – at the expense of his own, for now.

“I only have higher secondary education. If I (had pursued studies) at a university, (my) other siblings will not have a chance (to do so),” said Mr Mohd Zairul, who sends back a remittance of S$1,000 out of his S$1,400 monthly salary.

He added: “I don’t want to buy car, bungalow, I don’t want to become so rich. An ordinary life is enough for me. But I want all my family members to become highly educated.”

Two of his brothers have graduated to become an accountant and a textile engineer respectively, while another is enrolled in a medical school in France, he declared proudly.

Many of his peers who either wish to settle down in Singapore or reunite with their families in Bangladesh. Mr Mohd Zahirul’s big dream, however, is to join his brother in France and study English literature.

“I want to do that after my brothers and sisters finish their education...Because I want to translate my poems (into) English by myself, so that more can read (them). I write for humans, not only for Bangladeshis,” he said.

Mr Mohd Zahirul has written over 300 poems in Bengali, two-thirds of which were composed in Singapore. He also contributes to Bangla Kantha, a Bengali newspaper published here, where he shares his thoughts on challenges migrant workers like himself face, such as high agency fees and the poor quality of catered meals from their companies.

His love for literature intensified during his time in Singapore, after he found a circle of Bangladeshi friends who are passionate about writing poetry in their mother tongue. The group is mentored by Mr AKM Mohsin, the executive director of Dibashram, a drop-in centre for migrant workers here.

Every Sunday evening, the group gathers at a shophouse along Rowell Road to exchange poetry pieces and pointers.

While chatting with this reporter, Mr Mohd Zahirul broke into a spontaneous four-minute recital – he memorised it by heart - of a poem which he had penned about loss and love, which he loosely translated into English.

“Where are you

I am finding you,

Everywhere in the world

...

Suddenly, I see

A little far away, so cloudy

I see a river

But I didn’t get you

Where are you

Are you not alive?

I don’t believe it.”

Inspiration strikes him all the time, especially when he is toiling at work. “I keep paper and pen in my bag and wallet, when anything comes into my mind, I write down. After finishing work and dinner at night, I will check and edit,” he said.

He added: “I often think, my brothers and sisters, all are so highly-educated… I could not finish my education (although) I was a good student...If tomorrow I die, everybody will forget me. So I write about important (issues), when I die, maybe people remember.” KELLY NG

SHE FOUND A HOME AWAY FROM HOME

SINGAPORE — Talking about the bonds that she has forged with her employers’ four children over the past 26 years, Madam Ratnayake Mudiyanselage Rupa Ranjanee, a foreign domestic worker who hails from Sri Lanka, was animated and emotional. Mdm Ratnayake – or Aunty Rupa, as the children call her - recalled how one of the triplets, Geena, would call home regularly to ask her for tips on managing her apartment and laundry when the then-teenager went to the United Kingdom for her undergraduate studies. “I’d also teach her how to cook (over) Skype...Now she is back in Singapore, every night she still comes to my room and hug me, and ask if I love her...All the children are very close to me,” said Mdm Ratnayake, 55, as her eyes started tearing. The triplets are now 26 years old and their brother is 23.

Asked about her own family back in Sri Lanka, Mdm Ratnayake however became reticent. All she would say was both her children are married and they are “not close” to her.

Mdm Ratnayake left behind her family to come to Singapore to look for work in 1990. At that time, her daughter and son were just five and three years old, respectively.

Arriving in Singapore as a 29-year-old, Mdm Ratnayake, who barely understood a word of English then, was assigned to the Chatterji family who had just welcomed the birth of a set of triplets – two girls and one boy - the previous day. As the family conversed in a mix of languages - including English, Malay and Teochew - across different generations, Mdm Ratnayake hardly spoke a word in those early days and used hand gestures to communicate, making her employers rather worried. “I kept very, very quiet, was so afraid of saying the wrong things,” said Mdm Ratnayake.

Apart from the language barrier, it was no easy feat caring for the three babies at one time, despite help from her employers, Mdm Ratnayake recalled. Among other things, each child got hungry at different times and she had to keep a notebook of their feeding times.

When the triplets and their younger brother went to school, Ms Ratnayake also took on the role of disciplinarian, helping the children’s parents – who were both working - to make sure they finish their homework. “I supervise… and report to Mom,” she said.

Her contributions are recognised by her employers who have nominated her for the Foreign Domestic Worker of the Year Award. Organised by the Foreign Domestic Worker Association for Social Support and Training, the award will be given out tomorrow.

Mdm Ratnayake can now not only speak English and Malay fluently, she also understands Teochew and Mandarin, which she picked up from watching television programmes with her employers’ children.

But picking up the languages was shaded by what she considered to be her “greatest achievement” - learning how to cook.

“She earnestly took notes… and practised whenever she had the chance,” said Mrs Nandini Chatterji, 58.

Among the dishes that Mdm Ratnayake has learnt to cook from Mrs Chatterji’s mother include Teochew salted duck, curries and bulor hitam. Now that the children are grown up and she has more time on her hands, Mdm Ratnayake said she goes on YouTube to seek inspiration for new dishes, “so the children do not get bored”.

When not in the kitchen, she would spend her free time watching Korean variety shows with the Chatterji family and shopping with Mrs Chatterji. On Sundays, she volunteers at two temples here by cleaning their premises and cooking for visitors.

“If I can, I will stay (in Singapore) forever...If (I) can become a Permanent Resident, also can,” she said, adding that she only goes back to Sri Lanka once a year to visit her nieces and her 95-year-old mother.

Mrs Chatterji said her family will do their best to help Ms Ratnayake stay in Singapore.

“We have discussed this and my children say they don’t mind supporting Rupa financially. Singapore has become her home already,” said Mrs Chatterji.

But if her wish does not come true, Mdm Ratnayake said she hopes to buy a house in Sri Lanka for retirement. “Just for myself, to prepare for old age,” she said. KELLY NG

KEEPING A TRADITION ALIVE

SINGAPORE — Mr Vijayabalu Pandiyan left his home, a village in South India near Chennai, for Singapore when he was only 18.

“I had no choice, my parents and brother asked me (to) come, because in India I will not work, just play,” said the 24-year-old, who first started out here as a construction worker together with his elder brother.

Now a maintenance worker at the Singapore General Hospital earning about S$1,300 a month, Mr Vijayabalu looks forward to Sunday evenings where he would spend hours along with about 30 others at a field near Chinese Garden MRT station playing kabaddi, a contact sport which originated in ancient India.

Fiercely passionate about the game, Mr Vijayabalu rounded up a group of fellow enthusiasts here three years ago and started the weekly games. The players would be clad in bright-coloured jerseys often printed with the name of the village where they came from.

Said Mr Vijayabalu, “In India, I played everyday. Sometimes my father thought I (had gone to) school, but I went to play kabaddi. Wherever there is kabaddi, sure I will be there because I love kabaddi so much.”

His dream is to introduce the sport to Singaporeans but it seems a long shot so far. Many, including students and teens, have approached him to ask about the sport but most people “chicken out”, saying it is “too dangerous”, he said.

“I get a lot of injuries from kabaddi, that is (the) challenge, Singaporeans not adventurous,” he said. Kabaddi is played by both men and women. A popular sport in South Asia, it is now being played in countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada and Japan. Since 1990, the game has been played at the Asian Games.

Noting the rich cultural elements of the game, Mr Vijayabalu – who also plays football with his colleagues every Friday at a field in Kampong Bahru - lamented: “When I first came, some Singaporean Indians play. Now not anymore.”

Mr Vijayabalu keeps about S$300 of his monthly wages for himself and sends the rest home — a large part of which is used to fund his youngest sister’s college education.

“My mother wants to marry her (off), doesn’t want her to study,” he said, adding that he is he only one in the family supporting the 19-year-old, financially and morally, in her educational pursuits.

Mr Vijayabalu said he misses his youngest sister the most, apart from his kabaddi mates back in India and his late father. But he still hopes to stay in Singapore to make more money. “I don’t want to go back to India, because my family needs more money,” he said.

Besides, work will be the last thing on his mind if he goes back to India. “I (will) only think of kabaddi...Always calling my friends and disturbing them to (get them to) play,” he said. KELLY NG

UNDAUNTED IN HIS PURSUIT OF A BETTER LIFE

SINGAPORE — Having heard so much about how the influence of Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was instrumental in late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s resolve to open up China to the world, Dalian native Mao Xue Ying decided to see for himself if the Republic was indeed what it was touted to be.

But his experience in Singapore started on a negative note: Shortly after beginning work here in 2011, he found out that he was duped by his agent in China who had falsely promised him that he could opt for another job if he was not happy with being a cleaner, earning far less than his previous jobs in China, Japan and Spain where he worked in the construction and chemicals industries.

“Our district back in Dalian was not too shabby. With my experience and family background, I really did not think I should be working as a cleaner,” the 51-year-old said in Mandarin.

The thought of returning to China crossed his mind but it was soon snuffed out. “I really wanted to go back (to China). But it would be such a shameful thing to do, I’d be teased by neighbours...I had to brace myself to do it...Only through labour can we feed our loved ones,” he said.

Currently, Mr Mao tends to eight blocks of apartments in the Geylang area. His work day starts at 6.30am and ends more than 11 hours later. Not one to lament his lot in life, Mr Mao has sought to carry out his work professionally and in the process, he has built up strong rapport with the residents.

As he sat on the steps at Guillemard Apartments chatting with this reporter, several residents stopped in their tracks to join in the conversation, praising Mr Mao for his diligence in learning English and how he painstakingly collects the newspapers, old furniture and other scrap the households throw out to make a few more bucks.

One resident said: “He clears our junk, sells them to the rag-and-bone man and earns some keep for himself to live on… he is very hardworking.”

Mr Mao said he also tries to learn English by reading the newspapers that the residents throw away. “But (I learn) most of the language at church. Just a few weeks ago, I even shared a testimony in English,” said Mr Mao, who became a Christian in 2012 after a resident invited him to church during Mid-Autumn Festival that year.

Mr Mao said he has met fellow migrant workers at church, some of whom suffered similar predicaments with their employment agents.

With a better command of English now, Mr Mao said he sometimes feels more comfortable with Singaporeans than his fellow countrymen. “(Going to church) is what I look forward to most now,” he said.

To the residents of the Guillemard Apartments, Mr Mao is not just a cleaner. They showered him with concern when they learnt that he had to undergo surgery to remove a growth on his neck, Mr Mao recalled. “There’s an auntie who shares her vitamins with me,” he said.

Mr Mao, who has a college-going daughter back home, hopes to return to China in two years, after he has earned enough to pay for his father’s medical fees. “What can we dream of at this age? I only hope my descendants will not follow in my footsteps,” he said. KELLY NG

HE LIVED ‘THE S’PORE DREAM’

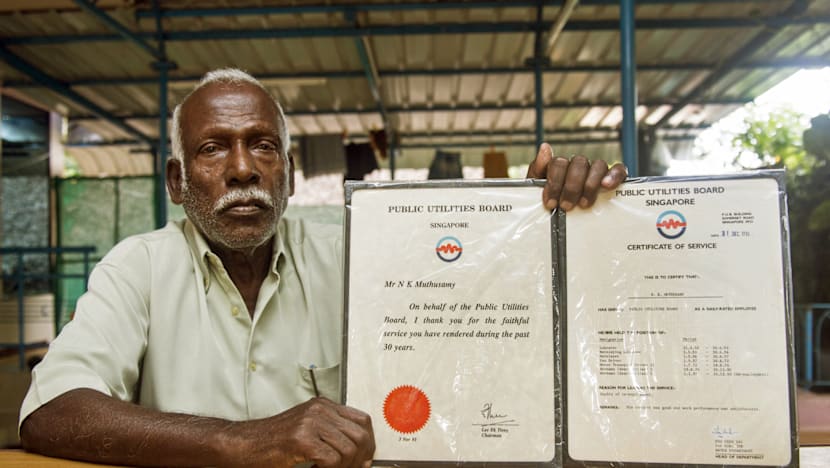

TAMIL NADU (India) — To many young villagers, Mr N K Muthusamy is the epitome of the man who has lived the Singapore dream.

But the 85-year-old former Singapore citizen is always quick to remind them that his multi-storey bungalow in his hometown, Alangottai, was built with his modest workman’s wages, starting at just S$1.80 for a day’s work in 1951.

That was the year when Mr Muthusamy, just 21, bought a ship ticket for about 100 Indian rupees (S$2) to take him from Nagappatinam, a port in Tamil Nadu, to Singapore. “The first time I made the trip, I was so seasick that I was quarantined on St John’s Island for three days before I could come to Singapore,” he said.

After that traumatic first experience, he decided to travel to Singapore by taking a taxi from Penang — the ship’s only pitstop after eight days at sea — for his subsequent trips.

For Mr Muthusamy, 1950s Singapore was not a destination to gush over. Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu, was more developed than Singapore at that time, he said.

At Havelock Road, where he first loitered around to find work, the young man was shocked to find an area choked with garbage. A year later, he found his first contract job with the Public Utilities Board (PUB) as a labourer, laying water supply and drainage pipelines across the island.

He later moved on to other roles at the PUB, as a driver and plumber. In the latter role, Mr Muthusamy served as part of a PUB team that provided 24-hour electric, water and gas maintenance, for 37 years. To earn some extra income, he took on part-time jobs at night, including a stint as a cleaner at the then Cathay Building.

By the time he left PUB in 1994, Mr Muthusamy was earning about S$8 a day, and Singapore’s physical landscape which he had had a small part in building had undergone a sea change.

It was also around this time that Mr Muthusamy noticed that the new generation of workers who came from his village to work in Singapore had different - and greater - expectations. They wanted to have the freedom to choose their jobs, and sought more time for after-work entertainment, he said.

In between his years with the PUB, Mr Muthusamy returned to his village, he got married in 1960 and started a family. But even with a wife and three children, he never thought of returning back to his village for good.

“In Singapore, I was problem-free. My only concern was the day’s work. I feel jobless and idle in the village. Even when I look for work, people will ask: ‘You have a big house. Why do you have to work for me?’,” he said.

When Mr Muthusamy secured his Singapore citizenship in 1974, he was finally able to bring his family to join him in Singapore.

They lived in a flat at Jalan Minyak in Bukit Merah that cost S$200 a month to rent. After PUB, Mr Muthusamy made his living by taking up temporary cleaning jobs.

In 2007, his wife discovered that she had breast cancer, and her medical treatment, which cost about S$14,000, put a financial strain on the family. Five years later, Mr Muthusamy himself had to undergo bypass surgery - and it was then that he decided to give up his Singapore citizenship after 38 years.

The whole family reluctantly moved back to their village in Alangottai and relied on his Central Provident Fund savings to get by.

With a hint of regret in his voice, Mr Muthusamy, who had hardly taken a day off for leisure when he was working, said: “If I were to add up the days, I had only spent two years in India for the 61 years I was in Singapore. Singapore is where I belong, but I’d missed the chance with Singapore. My last wish is to be able to go back and see the new city.” WONG PEI TING