In CSA's forensics lab, officers dissecting cyberattacks use sophisticated gadgets and race against time

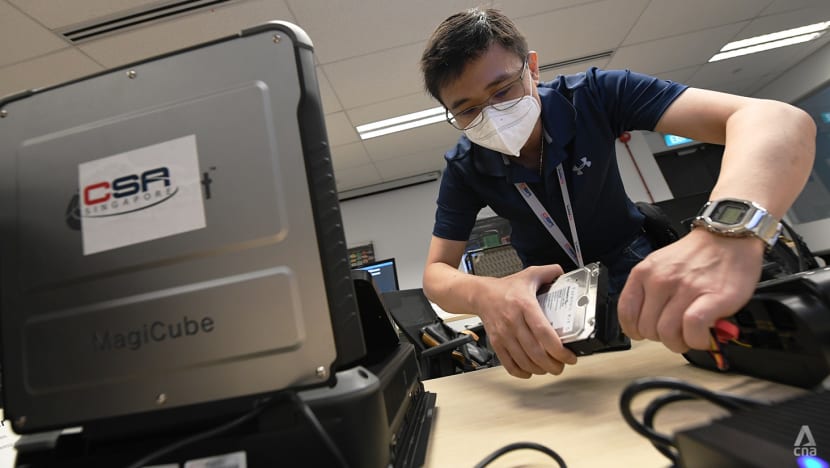

CSA senior consultant Adam Ho connects a hard disk drive to the forensic cloner. (Photo: CNA/Calvin Oh)

SINGAPORE: On Jul 20, 2018, the Government convened a press conference to announce that Singapore had fallen victim to its worst cyberattack.

Hackers had infiltrated the computers of SingHealth – Singapore's largest healthcare institution group – and stolen the personal data of 1.5 million patients, including Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong.

"CSA's (Cyber Security Agency of Singapore) forensics investigation indicates that this is a deliberate, targeted and well-planned cyberattack, and not the work of casual hackers or criminal gangs," then-Health Minister Gan Kim Yong said.

But what many did not see then was the work CSA had put in to produce this information in 10 days, from when it was first alerted to the breach.

A chunk of the investigation had taken place in CSA's forensics lab, a nondescript room no larger than a two-room HDB flat located in the Ministry of National Development building on Maxwell Road. CNA was given a tour of the lab in December.

“The timeline was very tight and we were racing against time; everyone was looking for answers quickly to address the issue," said Mr Ryan Chen, 36, a CSA senior consultant who coordinated operations between various teams during the investigation.

"We also had to provide information in a timely manner to the media and members of public. The investigation team had to provide the daily update to the stakeholders, even leading up to the Committee of Inquiry.

"They also needed to ensure that the full report was very detailed and accurate because it was a very serious issue. It was quite a stressful period for our guys."

CYBER DETECTIVES

Not unlike police officers, CSA officers have to visit the "crime" scene, collect evidence and process it, then determine the root cause of the incident, the attacker's intent and whether any data was stolen.

CSA officers also use specialised equipment to extract and copy data from storage devices, allowing them to analyse the threat, check for system vulnerabilities and recommend preventive actions.

If an attack is ongoing, as was the case during the SingHealth breach, the priority is to block the attacker from accessing the system and close other potential backdoors that could be exploited.

Mr Chen said CSA's primary role in those 10 days was to help contain the cyberattack, reconstruct the attack timeline and assess its impact, including what data was stolen and whether records were modified or deleted.

There was also "pressure" on the authorities to promptly inform affected individuals whose data may have been stolen, he said.

"We were dealing with a skilled and sophisticated threat actor who was also very persistent and well-resourced," he added.

The SingHealth attack was likely conducted by a type of advanced persistent threat group that is usually state-linked, then-Minister for Communications and Information S Iswaran later revealed, although he declined to identify the country for reasons of national security.

Mr Chen said the incident stretched CSA's resources as officers worked long hours for many days, often under pressure by stakeholders like senior officials from different ministries and the press.

"I think the stress cascaded down to everyone in the team. We were trying to shield the guys from the queries outside, because people were asking, like, a lot of questions," he said.

"The last thing you wanted was the technical guy to be constantly disturbed – like asking for progress every few hours. And if you couldn’t really focus, it became quite disruptive to the investigation.

"The prolonged operations would affect their morale as well. The tension was high then, so we needed to shield them from having to front the engagement with stakeholders."

Other cases, like ransomware attacks, also require a fast response as victims have lost their data to encryption and must pay hackers to get it back, said CSA senior consultant Adam Ho, 38.

CSA officers will first try to determine the ransomware variant to understand its behaviour, like whether it encrypts specific file types or disk drives, before deciding what to do next. They will also look online for potential decryption keys.

"We do not recommend paying the ransom. Doing so does not guarantee that the data will be decrypted or that the data will not be published by threat actors," Mr Ho said.

"It also encourages the threat actors to continue their criminal activities and target more victims. Threat actors may also see organisations who pay the ransom as a soft target and may strike again in the future."

Instead, organisations should take preventive measures to secure their computer infrastructure and systems, and come up with a backup and recovery plan for business-critical data, he added.

GOLDEN IMAGE

Critical Information Infrastructure (CII) sectors – such as healthcare, government, banking and finance – that are hit by a cybersecurity incident are required by law to report it to CSA.

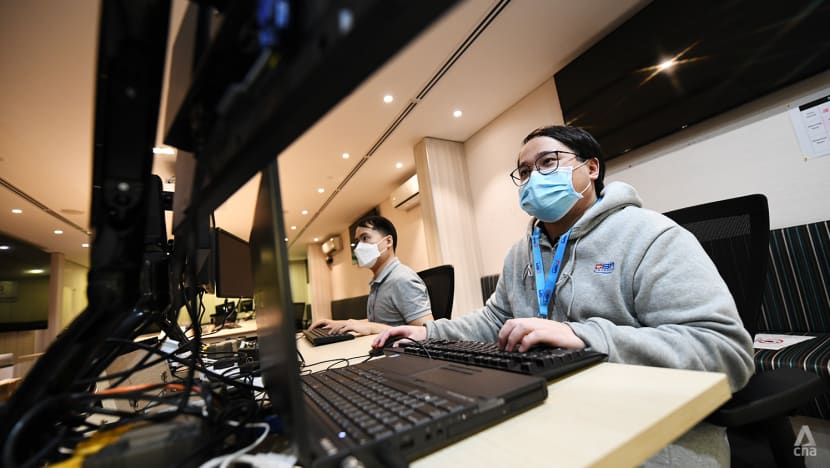

The report will go to a CSA manning team, which also monitors global and local reports of cybersecurity incidents. The team works in a large operations centre, containing numerous workstations and TV screens next to the forensics lab.

CSA will coordinate any incident response with CII sector leads and owners. The sector lead in the SingHealth breach was the Ministry of Health.

The manning officer and an incident response team leader will perform an initial triage, and deploy officers based on the incident's scale and severity.

Officers at the incident site will ask for critical information, like when employees noticed malicious or suspicious activity in their devices, as well as the number and type of devices affected.

They will also use specific tools to collect digital evidence like storage devices, network logs and other material relevant to the case.

This evidence, called "artefacts", will be brought back to the forensics lab and cloned. The original evidence is called the "golden image" and will remain untouched while officers work on the cloned copy.

"Making a copy of a hard disk is an essential step to making sure that we retain the integrity of the evidence," Mr Ho explained.

"There are chances the data stored in the hard disk may be affected during our processing. Thus, it is essential to make a clone copy of the original in the event we need to retrace our investigation process."

FANCY EQUIPMENT

While the CSA forensics lab might look like the average computer lab, a closer inspection reveals fancy-looking gadgets, some packed in large hard case field kits, lying on rows of tables.

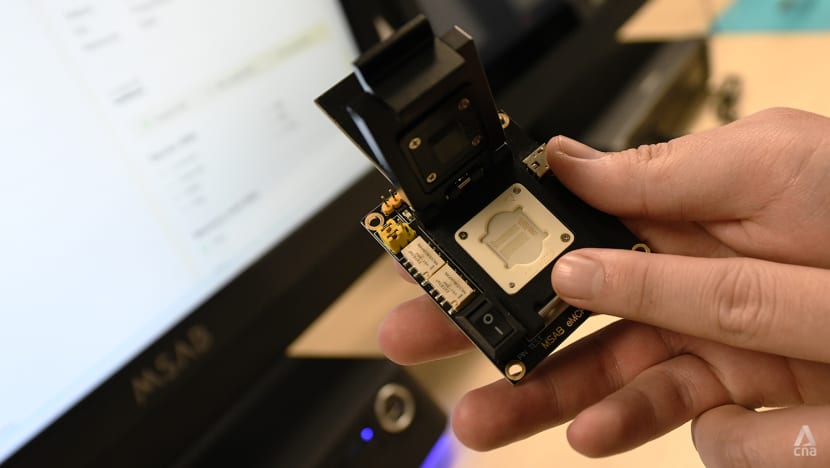

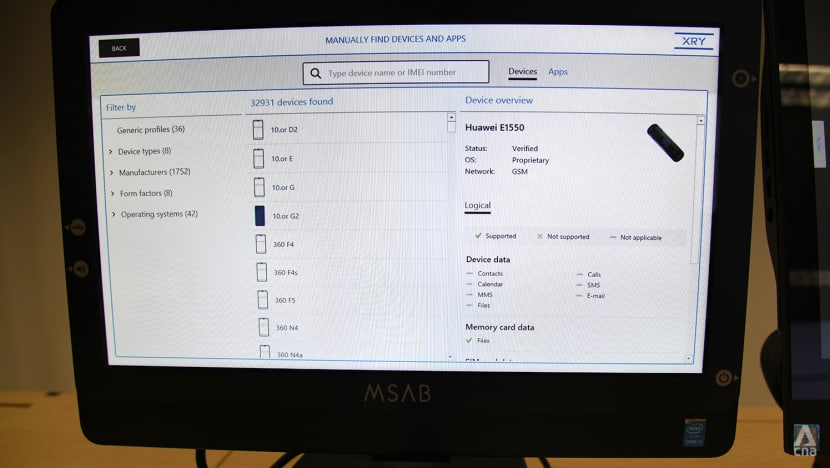

These industry-standard devices can swiftly extract data from storage drives like hard disks and mobile phone chips.

One of the devices appears to be an oversized handheld gaming device but is actually a forensic cloner. It is connected directly to a hard disk to quickly copy large amounts of data. A bigger cloner, which looks like a tablet attached to a suitcase, has dedicated hard disk slots.

The cloners come with basic built-in forensic examination software to determine if the storage drive has been infected.

Officers can also extract mobile phone data by dismantling the phone and inserting its storage chip into a slot on another device. If the phone is damaged, officers can try removing the chip using a soldering station.

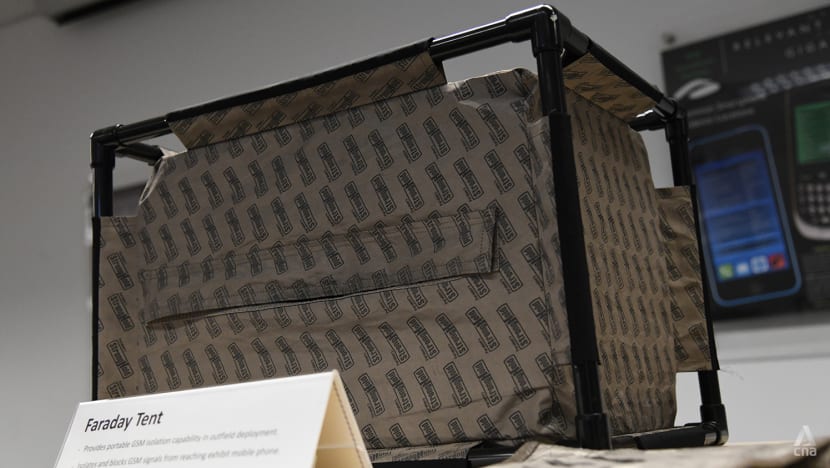

There are more mundane tools like cable adaptors for older phone models and a tent that cuts off a phone's communication to prevent its data from being remotely erased.

Mr Ho said knowing which tool to use and how to use it during investigations comes with experience, especially as the technology is consistently evolving.

"That’s why we need to pass down our knowledge. We also need to build up on new technologies, to ensure our officers' skillsets are up-to-date," he added.

NOT YOUR EVERYDAY JOB

The job, however, is not just about sitting in a lab and using technical equipment.

Mr Chen recalled how, in 2018, he responded to a cybersecurity incident related to a CII sector and visited a secure location underground where the organisation's servers were located.

This "remote" room was was different from the usual server rooms found in an office environment, Mr Chen said, adding that malware had been detected on the server.

Mr Chen and fellow CSA investigators interviewed different staff members to get information on the system, and with the help of the organisation's on-site IT staff, managed to determine the cause of infection and recommend steps to clean up the system.

"It was a unique experience for the team as we got to enter a well-hidden location to investigate an infection, and instead of relying on logs, we had to quickly conduct interviews to put the pieces together," he said.

Mr Chen stressed that CSA's officers on the ground have to think on their feet by assessing the situation and determine the next course of action.

"For example, some operating system may have their USB ports disabled, are we able to obtain the artifacts via the network port? These are the typical challenges that our officer faces when dealing with a wide spectrum of networks across various sectors," he said.

Mr Chen said the investigation will involve stakeholder briefings, recommendation of mitigation measures and a review of IT governance policies.

It will also have to address some key questions, such as the system's anti-virus software update timeline and why it did not pick up on the infection earlier.

"Contrary to general impression that cyber investigation is about finding artefacts from computer hard disks, the biggest challenge is often the management of stakeholders and addressing the gaps in IT governance within the victim organisation," Mr Chen added.

"More often than not, structures and processes are harder to change, compared to removing a malicious file."