IN FOCUS: After struggling in school for years, these adults with dyslexia now embrace their strengths

While many have their dyslexia first identified in primary school, their challenges don’t disappear when they grow up. A politician, an artificial intelligence ethicist and an entrepreneur tell CNA how they learnt to thrive at work.

People’s Action Party (PAP) Member of Parliament (MP) Dr Wan Rizal, AI ethicist Chan Pui Yan and entrepreneur Edward Yee. (Screengrab/Photos: CNA; Edward Yee)

SINGAPORE: He was the boy who cried in class because he had trouble copying down what the teacher wrote on the board.

When he thought he had copied something correctly, it turned out to be something else. Or he would be too slow, looking up and down so often that he earned a scolding from his primary school teachers.

His mother, too, would scold him at home, making him wonder: “Why can’t I get the spelling right, no matter how many times I practise it?”

At first, he pegged his struggles to myopia. But when he continued lagging behind even while wearing spectacles, he eventually came to realise what it was: An inability to read and write well.

Today, more than three decades later, his dyslexia goes unnoticed by most – at least if they watch him speak in parliament.

Dr Wan Rizal, a People’s Action Party (PAP) politician, is no longer plagued by spelling or confidence issues. In fact, the Member of Parliament (MP) accepts his weak spots.

“I'm not shy to say that I could struggle a bit with speeches. I just have to make sure the font is bigger … and if the words are too long, I just have to manually cut it up. But other than that, I don't see an issue,” the 45-year-old told CNA.

Many adults with dyslexia are no stranger to his struggles – and like him, have found ways to thrive.

"THEY ASSUMED I DIDN'T HAVE THE ABILITY"

Dyslexia is a life-long learning difficulty which affects skills involving accurate and fluent reading and spelling, said Fong Pei Yi, registered psychologist of assessment services at the Dyslexia Association of Singapore (DAS). It can be attributed predominantly to a deficit in phonological awareness, or the ability to work with speech sounds in languages.

Children with dyslexia tend to be slow to learn the alphabet, and struggle with reading and spelling. As such, many are identified during their primary school years.

Ms Chan Pui Yan’s dyslexia was noticed by teachers and school counsellors early on in primary school, when her reading and writing abilities didn't match her speaking fluency and understanding of various topics.

The 36-year-old, now an artificial intelligence (AI) ethicist, recalled being “very self-conscious and nervous” when put on the spot to read.

“When people saw my difficulty in processing a piece of text, they would often assume I did not have the ability to comprehend the topic,” she said, adding that they would make condescending remarks or offer to teach her.

Family and friends also attributed Ms Chan’s writing errors to carelessness and a lack of effort. And they thought she was being defensive or lazy when she said she had checked her work and still couldn’t spot the errors.

“Because for them, they cannot ‘see’ words wrongly,” she explained. “They cannot relate to my experiences and it may be natural for them to interpret it as carelessness, as that may be the main reason that they themselves make errors.”

Similarly, 28-year-old entrepreneur Edward Yee recalled that his dyslexia posed more of a challenge in primary and secondary school. Unlike many, however, he did not have issues with reading.

Instead Mr Yee struggled with subjects that involved memory work, such as biology and history.

“I just could not remember or memorise what was needed. It was in those classes that I often felt like I wasn't smart enough or capable enough,” he said. On the other hand, he excelled in subjects that relied more on conceptual understanding.

Dyslexia can also affect verbal working memory and processing speed, noted DAS’ Fong. Even though many may learn, with "great effort", to compensate for their underlying difficulties by the time they reach adulthood, they may also lack "automaticity” or reflex. This affects their speed in completing tasks.

And as tertiary education and workplace demands increase, these difficulties tend to become more pronounced.

CHALLENGES IN ADULTHOOD

When Mr Yee and his wife first started dating, she took his forgetfulness as not caring about important occasions. Having learnt that her husband’s inability to remember events isn’t intentional, she now sends him calendar invites to help him note down key dates.

Similarly, Mr Yee understands it can be frustrating for his colleagues if he forgets important details or instructions, especially when information is time-sensitive and critical.

He writes notes to capture details from conversations and meetings, and relies on to-do lists and calendar events to recall information. But this habit does not come naturally to others and requires "work together to make (it) work", he admitted.

Dr Wan Rizal, on the other hand, doesn’t believe anyone in parliament is aware of his dyslexia as his struggles tend to show up in writing, not reading. Besides, gone are the days when his spelling mistakes in composition writing would result in deducted marks.

Still, he acknowledges his dyslexia in certain situations rather than avoid it completely. As a lecturer at Republic Polytechnic, he feels his dyslexia can be “quite apparent” to his students.

“When I write notes, I tend to scribble on the board to hide some mistakes. My students (understand what I’ve written) because they see it as a whole sentence. But sometimes I explain and say sorry that I missed out certain letters,” he said.

Dr Wan Rizal noted that what he goes through – dropping or mixing up vowels – is "minor”, compared with others whose dyslexia may even hinder them from driving as they can misread road signs.

In adulthood, dyslexia may also present challenges in planning, organising and managing time, materials and tasks.

These adults may avoid writing or take longer than their colleagues to process emails due to issues with written and spoken language. They may also spend a longer time reading, especially when it comes to jargon-laden texts, noted Fong from DAS.

Their work can be filled with errors, making them appear careless to their lecturers in school or supervisors at work, she added. “This may also lead to an underestimation of their abilities, compelling them to attend courses or seek jobs that are below their actual capability.”

Listen: How Chan Pui Yan learnt to accept her dyslexia

Ms Chan, who faced such issues in primary school, still managed to keep up with her peers and receive As in her classes. But things changed when she entered university.

After a professor assigned a 20-page reading of engineering material to be completed in two days, she realised she could not read at that pace.

“I would look at my friends … They just sit and read, read, read, read and they’ll be done. I’d be still reading, maybe six, seven hours later, and I’d be so swamped,” she recalled.

But she added that this hurdle still didn't compel her to seek help. Ms Chan was less daunted by the need to complete her academic readings, than she was by the thought of being recognised as having a learning difference.

But when an AI hiring system rejected her job application because she couldn’t read scenarios and answer quickly enough during an assessment, she could no longer ignore her struggles.

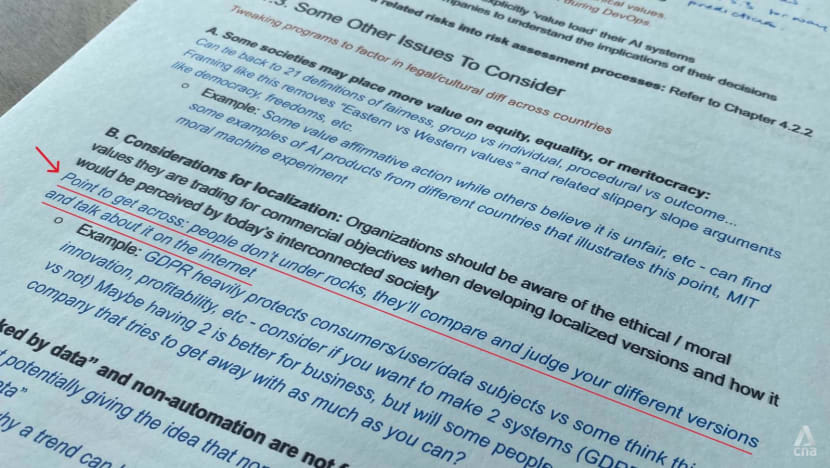

Today, the head of AI ethics and governance at MSD, a multinational pharmaceutical company, has come full circle. Her job – incorporating responsible AI principles and practices into policy – involves a heavy amount of reading and writing.

When she inadvertently “drops" words while reading, she will realise the information doesn't quite make sense, and will reread the text. There are times, however, when she doesn't realise she has made a reading error, resulting in an incorrect understanding of the text.

“If it's mission-critical, I’ll make sure I read the email three, four times,” she said — which means taking longer to go through and compose emails. “Sometimes I even put my hand up to the screen (to point at) every single word.”

These challenges extend to writing. For instance, she finds keying in credit card numbers, OTPs (One-Time Passwords) and CAPTCHAs “anxiety-inducing”. In their long strings of numbers or symbols, the characters look similar and there are no contextual clues, she said.

Ms Chan pulled up the above gif to help CNA understand how words sometimes appear to her, though she acknowledged it was “a little bit exaggerated”.

“Not like every single letter switching, but it’s like, sometimes, you look at it, and you swear it says something, and then you blink and you look at it again, and then it says something else, and you’re like, how can that be? Am I hallucinating? Am I losing my mind?” she said, tongue-in-cheek.

What has changed over time for Ms Chan is an acceptance of dyslexia, and learning how to manage her weaknesses.

She focuses her reading efforts on essential tasks, fiction books and hobbies, she said. “I read only what really interests me and I don’t worry about reading it comprehensively.”

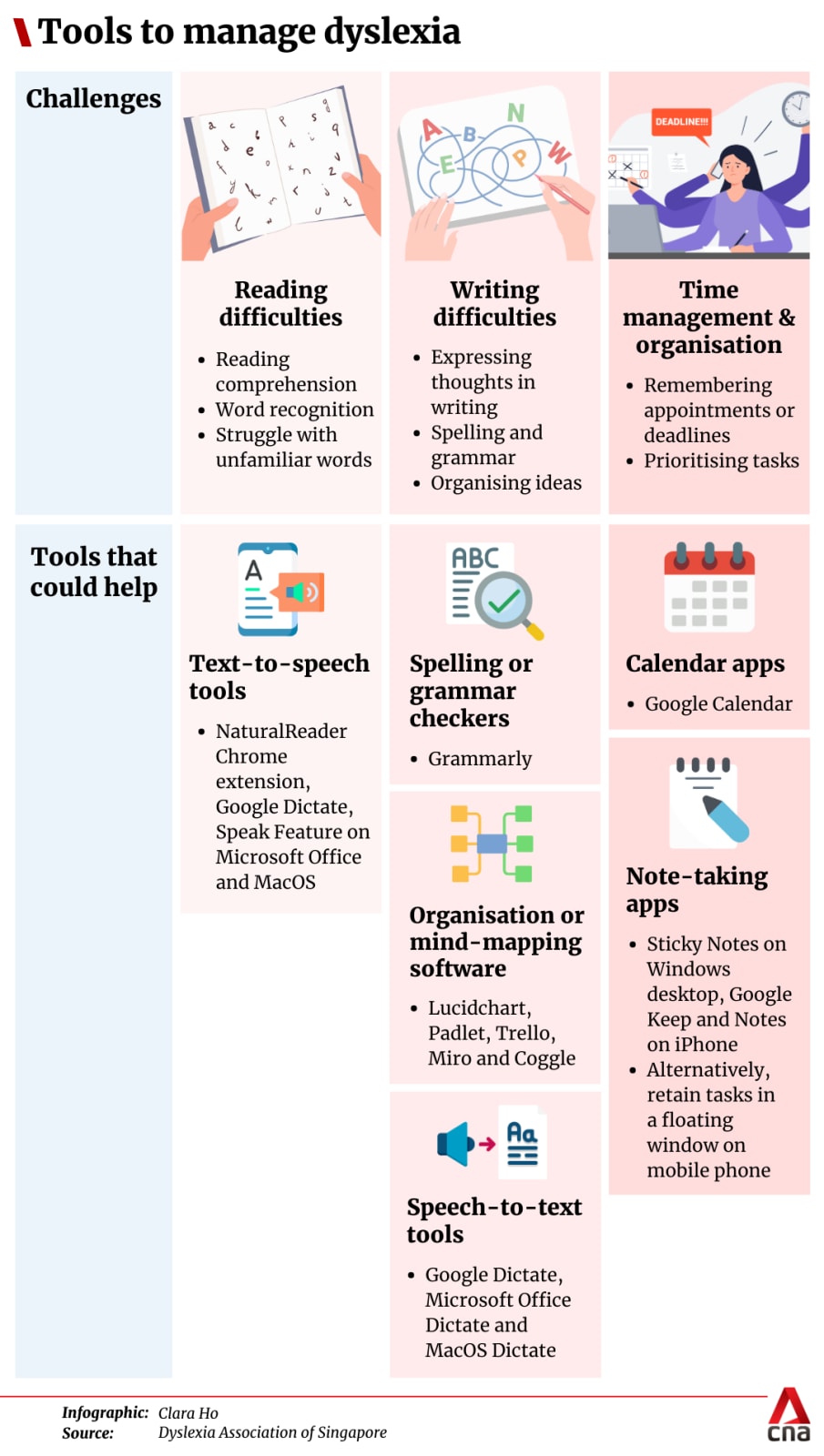

Technology, in particular audiobooks and text-to-speech tools, plays a significant role in her life.

“I also extensively colour-code my notes and drafts as it helps me to quickly identify and organise information without having to read it,” she added.

"A DIFFERENT WAY OF SEEING THE WORLD"

For some people with dyslexia, it was loved ones or teachers who made all the difference.

Mr Yee, who was the 2019 Singapore Rhodes Scholar, believes his parents embraced dyslexia before he did.

His mother first caught several signs in her son, and suggested he get diagnosed in primary school so they could understand the condition better and learn how to deal with it. Mr Yee recalled that his parents approached his dyslexia in a manner that shielded him from any stereotypes.

“I can see in hindsight now … that (my parents were) very deliberate in how they shared the news with me,” he said. “I didn't see it as a disability or anything. It's just kind of a different way of thinking and seeing the world. I think that's really how they explained it to me.”

Mr Yee added that his father taught him specific systems to use in school, such as colour-coded highlighting of material. He still does this today, having trained his brain to instantly recognise what each colour means.

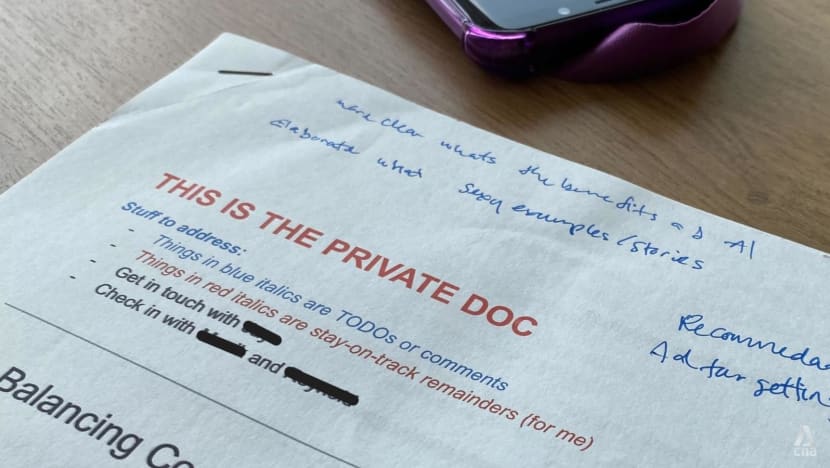

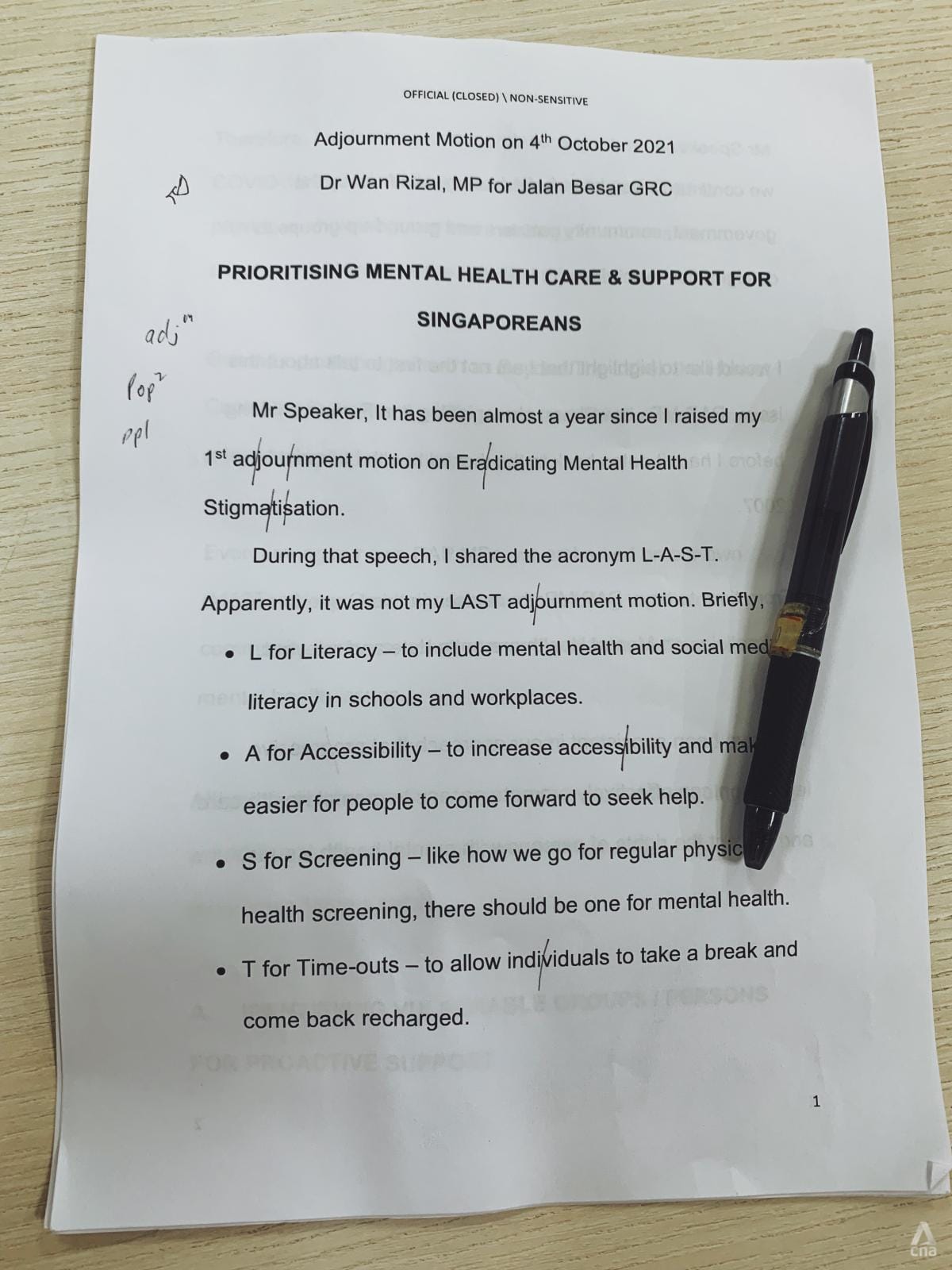

Dr Wan Rizal, too, still uses a strategy picked up in secondary school from his then-teacher Zainal Sapari, who was also a PAP MP.

Utilising short-form note-taking for humanities subjects also helped Dr Wan Rizal discover the "beauty of studying”, he said.

“(The short form) is really powerful for someone like me. I don’t have to write the whole word ‘population’, I just write ‘pop2’ and I know it’s ‘population’. And if I write ‘pop’ with another number, it becomes (another word). It becomes easy for me,” he said.

As an MP, Dr Wan Rizal embraces this strategy in drafting speeches. He breaks up a long word by drawing lines in between the letters, or simply avoids using the word. The latter has worked to the MP’s advantage.

“The message is not lost (just) because things are simple. And nowadays, people don't want to hear very long speeches anyway, they want (them) to be more direct and concise,” he said.

"I like short sentences; I can’t hold long sentences in a speech. I worked to my strengths and I realised it’s easier for people to understand ... To choose 'easy' words is not easy too."

There were, however, initial hiccups. His legislative assistants didn’t understand why he would heavily edit speeches they had drafted for him. As hardworking as they were, they tended to use long sentences and very long paragraphs, said Dr Wan Rizal.

“That’s not me. I cut their speeches a lot. I butchered them up very badly, because they have to be mine at the end of the day."

When asked why he would remove huge chunks in drafted speeches, he has explained his preference for simplicity — but stopped short of sharing his dyslexia.

NO SHAME IN SEEKING SUPPORT

Aside from developing strategies to manage their challenges, those who spoke to CNA stressed the importance of seeking help early.

Dr Wan Rizal, who often champions mental health issues in parliament, said he was willing to talk about his dyslexia for this story because he wanted to encourage parents to take the first step for their children.

“Sometimes I visit families and they don’t send their kids to school at all. I ask why and they say it’s because the child struggles … Sometimes there are other reasons behind it,” said the MP who oversees the Kolam Ayer ward in Jalan Besar.

“I might not be an expert, but I want them to go to the polyclinic, get their first level of developmental checkup and see how they can improve. I want people to know that there are a lot of interventions available right now for our children.”

Dr Wan Rizal speaks from experience, having spotted signs of dyslexia in his children. Once, while trying to get his youngest child to recognise sight words – common words children are expected to recognise instantly – the kid mixed up the letters “n” and “o”, reading “nothing” as “on-thing”.

“I see where it's coming from,” he said, adding that his children do get "a lot of support" in school.

“Even my students who struggle with dyslexia get extra time to finish their work. And that’s fine, because they take a bit longer to read and synthesise the content.”

Despite many being identified when young, DAS' Fong said it was possible for adults with dyslexia to remain unaware and undiagnosed. And this can have repercussions.

A 2020 study by the association, focused on entrepreneurs with dyslexia in Singapore, found that almost 50 per cent of those who identified as dyslexic were not previously diagnosed. They may, however, have assumed their experience was the norm, or found other ways to get around their challenges, added Fong.

She cautioned that a late or lack of diagnosis for adults could have made it more difficult for them to achieve their potential.

“They may develop poor self-confidence, self-efficacy and self-esteem from their experience of performing poorly despite their efforts during their schooling years," she said. "Subsequently, they may pass up valuable career opportunities for more basic work that they believe are more suited to their abilities."

Once diagnosed, individuals should be honest about how dyslexia affects their abilities and relationships, said Mr Yee.

“This might be scary, so you could start with those who you are more comfortable with first — practice makes this more normal,” he said.

He has found that being upfront about his dyslexia hasn’t affected his work or how he is perceived by others. In fact, it helped him gain confidence as an entrepreneur.

Some with dyslexia worry that the support they seek might put others in an unfair position.

But DAS’ Fong explained: “Fairness is not about giving everyone the same treatment but providing what is needed so that everyone, including those with learning differences, can perform a required task.”

She added that providing support is not about reducing expectations, but facilitating ways for the individual to meet expectations.

After denying herself help in the past, Ms Chan, for one, has embraced the fact that reading is not something she can master by "trying harder", just as she wouldn’t tell herself to “squint harder” without spectacles.

“It’s just not worth it to try to keep pretending that (your dyslexia) is not real, if you do struggle,” she said.

“The reasons why I (didn’t speak up) before was some combination of pride and some misguided shame that you shouldn't even have. You don't deserve to deal with that and to carry that with you.”

PLAYING TO STRENGTHS

While many seek to manage their dyslexia-related weaknesses, their innate strengths should be harnessed too, said Fong.

These individuals may have good people skills and may be adept at "people-reading”. They may also have strengths in spatial ability which are useful in occupations like architecture and interior design, she added.

Mr Yee believes he has his dyslexia to thank for his ability to visualise well. He uses this to build “mental structures” for himself, using various apps and platforms.

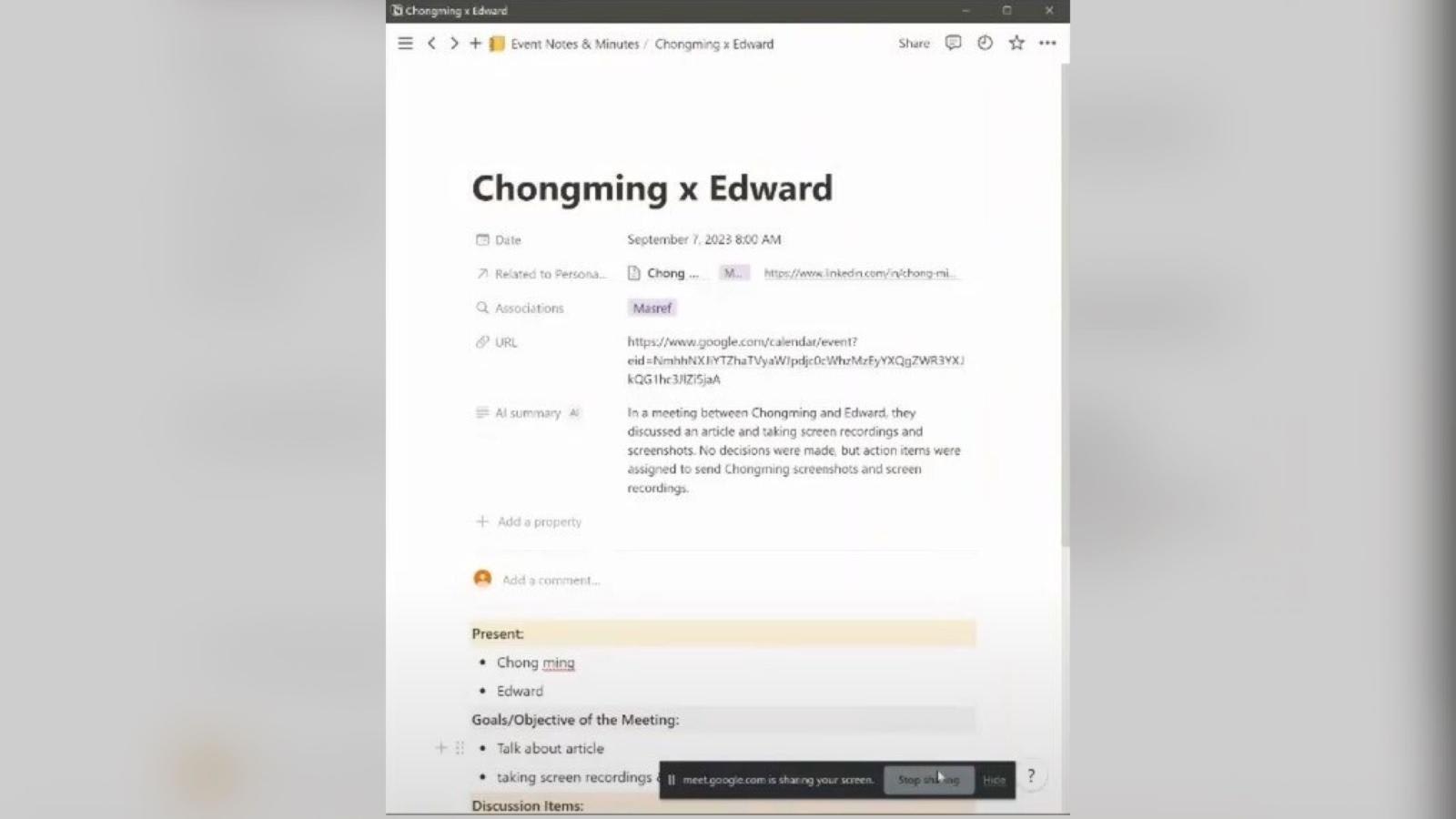

These "structures" are essentially an organisational system and what he calls a “second brain”, which remembers better than he can. It allows him to absorb, categorise, recall, access and process information efficiently.

“If you asked me what I have on tomorrow, I have no idea either. But I know exactly how to find it and how to find it very quickly,” he explained.

For example, Mr Yee sorts his emails into categories and adheres to a zero-inbox policy. His calendar is also consistently updated and synchronised with other software.

One of these is productivity tool Notion, which he uses to automate tasks like clipping articles and setting recurring events to improve his workflow.

Organising his life in this manner allows Mr Yee to “break down the chaos into smaller problems to solve”, and prioritise effectively.

This way of thinking has also pushed him to see connections and join the dots between seemingly disparate ideas, he said, calling it an asset in his work as competing priorities and the lack of a system tend to be prevalent in entrepreneurship.

According to colleagues, his "second brain" can perform even better than other tried-and-tested ways of doing things.

“I think, by necessity, I had to become a bit more big-picture and a bit more systematic in how I do things,” said Mr Yee. “One of the ways people describe dyslexia which relates the most to me (is that) we see the world in images instead of words.”

Relatedly, Dr Wan Rizal's understanding of how “nothing comes in silos” helped him comb through lengthy literature reviews to understand certain concepts, when he was pursuing his PhD. He also pointed to pattern recognition as a dyslexia-related strength.

“In secondary school, they got us to do some IQ tests. (They dealt) with words, but again it’s context, it's about pattern recognition, it's about application. And that's how I realised we do quite well in certain tests, especially ... in terms of (finding) similarities,” he said.

“Although words are sometimes a struggle, patterns and looking at (overall) context and how things could turn out is something we own a bit more than others.”

Knowing you have dyslexia is not the "end game”, the MP concluded. “It’s really a start to understanding other strengths.”