FAQ: Craving nasi lemak topped with crickets? What you need to know about eating insects

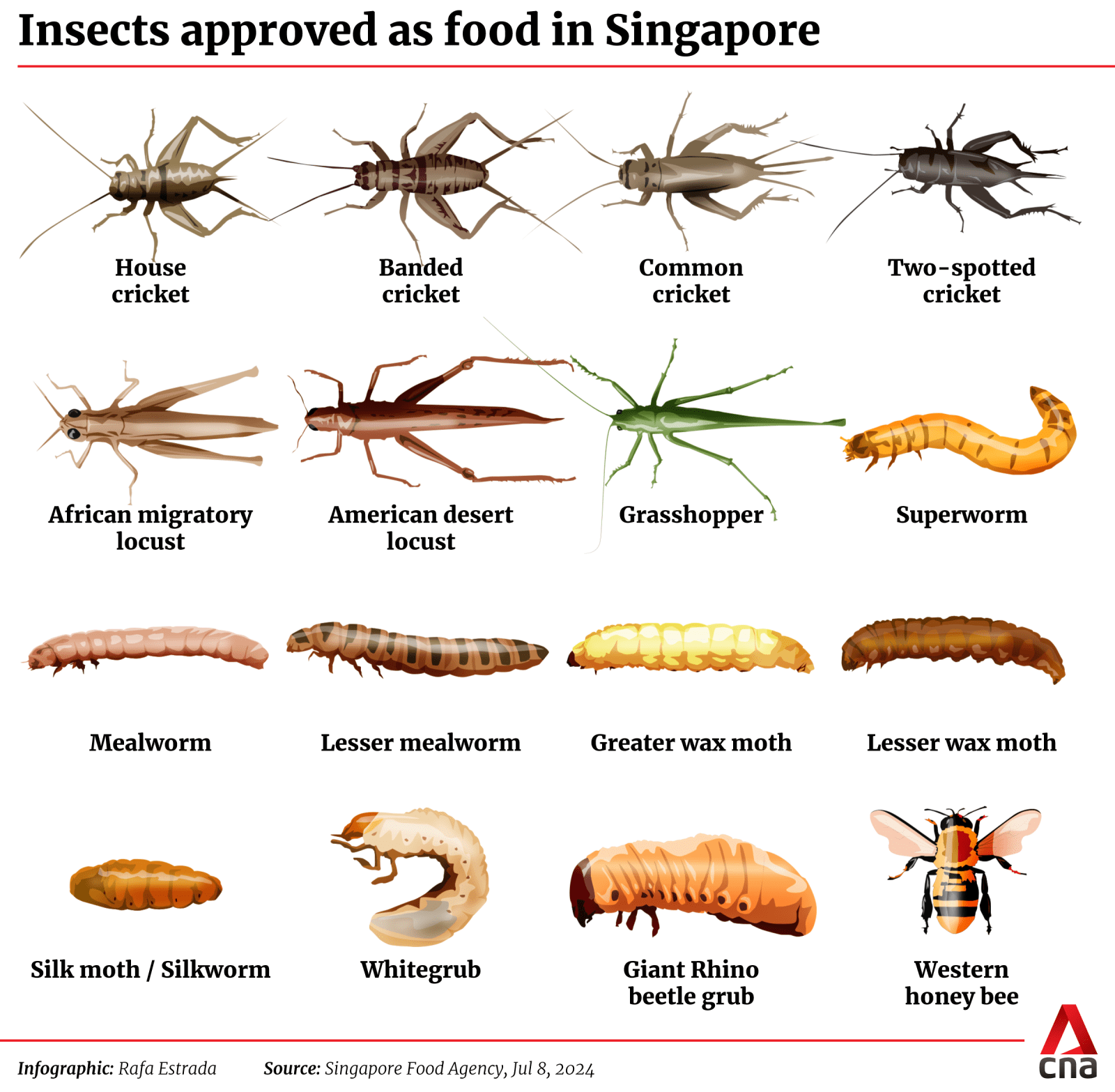

Could I be allergic to insects? Are they nutritious and halal? CNA looks at some commonly asked questions after Singapore approved 16 species of insects as food.

Could stir-fried grasshoppers become a dinnertime norm? (File photo: iStock)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Social media has been abuzz since Singapore approved 16 species of insects as food.

A variety of crickets, silkworms and the Western honey bee are among the critters that will soon be on menus and available in stores.

Curious about trying your first bug but still have some doubts? CNA looks at some commonly asked questions.

COULD I BE ALLERGIC TO INSECTS?

If prawns make you itch, consider holding off on trying these multi-legged snacks.

Those with shellfish and crustacean allergies may be allergic to insects as well, according to the Singapore Food Agency (SFA).

The agency said on its website that the same kinds of allergenic proteins from shellfish and crustaceans are also found in insects.

The Allergen Bureau, an industry body representing food industry allergen management, noted on its website that crickets, mealworms and other insects are closely related to crustaceans, increasing the chance that those who are allergic to shellfish will have the same reaction to insect protein.

Consumers should look at product labels as all pre-packaged food must indicate the “true nature” of the product. A snack may not come across as containing insects from the packaging alone but it could be on the ingredients list.

ARE INSECTS HALAL?

Earlier this year, the Office of the Mufti of the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) released a publication outlining guidelines on novel food.

In setting out its religious position regarding insect-based alternative protein sources, the Office of the Mufti said that food products derived from insects are generally permissible unless the insects are harmful or there is a specific ruling that clearly prohibits them.

It referenced a fatwa issued in 2023 stating that the production of alternative proteins is a necessity in today’s world.

“While there may currently be an abundance of food sources, investing in alternative protein sources now may help society better prepare for a more sustainable food future,” it said.

“The Fatwa Committee of Singapore has ruled that protein produced from insects is halal,” added MUIS' publication titled From Lab to Table: Novel Food from Islamic Perspective.

In response to queries from CNA, MUIS said on Thursday (Jul 11): "In view of this being considered novel food, Muslim consumers may opt for halal-certified insect-based food products for added assurance."

WHAT’S THE NUTRITIONAL VALUE?

Those who are health conscious might be familiar with the "magic words" – protein, protein and more protein. Insects are protein-rich, though the concentration may vary between species.

A 100g serving of crickets generally contains about 65g of protein, more than twice in a similar serving of chicken breast.

Those put off by the ick factor can boost their protein intake in other ways instead of eating whole insects. Simply opt for alternatives such as insect-based protein powder that can be included in smoothies, bars or other dishes.

Apart from being protein-rich, insects can provide several beneficial fatty acids such as omega-3 and other unsaturated fatty acids, Assistant Professor Nalini Puniamoorthy of the National University of Singapore's (NUS) Department of Biological Sciences told CNA.

“They can also be a good source of vitamins, such as B12 and riboflavin, as well as minerals, such as iron and zinc. They are also some studies that suggest that chitin, found in abundantly in insects, can aid in digestion with antimicrobial properties,” she said.

Chitin is the primary component of many insect exoskeletons.

Director of Nanyang Technological University's Food Science and Technology Programme, Professor William Chen, said that the protein content of certain insects could potentially be higher than the protein content of animal meat.

"The edible insects especially at the early stage of their development (larvae) are rich in healthy lipids/fats. In general, edible insects are rich in micronutrients such as vitamins, Omega-3/Omega-6 fatty acids, minerals and antioxidants. Interestingly, edible insects are also rich in fibre."

While insects are commonly prepared as deep-fried food, there are healthier cooking methods without compromising on texture.

Roasting, baking or even air frying can retain the crispiness of insects without additional trans fats, said Asst Prof Puniamoorthy.

“There are also delicious recipes that involve the boiling, braising, or steaming of insects such as the beondegi or silkworm pupae in South Korea. There are also products that simply use dehydrating to dry the insects or grinding insects into powders to be used in baking or incorporation into other foods.”

Prof Chen, who is also the director of Singapore Future Ready Food Safety Hub (FRESH), said that frying is an easy way to kill potential pathogens as well as to extend the shelf life of the product.

"However, frying may also destroy the nutrients and consuming oily fried insects may not always be healthy. One alternative way of preparing insects for consumption may be to bake them to achieve the same objectives. It is not advisable to consume raw form of insects."

DOES THE ENVIRONMENT BENEFIT?

Nutrition reasons aside, opting for insects on the dinner table can be a plus for the environment as well.

“I think it is important to emphasise that insects are a highly sustainable food source. They require less land, water, and feed compared to traditional livestock, and most importantly, they have a reduced environmental footprint which can support greener food systems,” stressed Asst Prof Puniamoorthy.

“Insects present a promising solution for nutritional value and as a society, we may need to adapt and shift.”

Asst Prof Puniamoorthy recently gave a keynote at the Insects to Feed the World Conference and is currently leading an interdisciplinary team of researchers.

The study, funded by Singapore's National Research Foundation, is developing a blueprint for using insects for food waste management and food production in urban systems.

Prof Chen also noted that insects can be farmed in a controlled environment and have a faster growth rate, therefore representing a sustainable food source for the growing world population.

Insects are also an overlooked source of protein and a way to battle climate change, the World Economic Forum (WEF) said in 2022.

Among the advantages is that edible insects can produce equivalent amounts of “quality protein” when compared with methane-producing animals.

Beef has the highest greenhouse gas emissions on a per kg basis and pork came out tops on a per capita basis, according to a Singapore-centric study commissioned by investment firm Temasek and carried out by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) and Deloitte, and published in 2019.

Insects, on the other hand, produce much smaller quantities of greenhouse gases per kg of meat than livestock like cattle and pigs.

A pig produces between 10 and 100 times as much greenhouse gases per kg compared with mealworms for example, a 2011 study by the Wageningen University & Research, which specialises in life sciences and agriculture, said.

WHY ARE WE EATING BEES?

The importance of bees as pollinators is well-known, so it might seem counterintuitive at first that they can also be eaten as food.

A study published in the Journal of Apicultural Research in 2016 noted that many cultures, including those in Thailand and Australia, consume honey bee brood, also referred to as larvae, as a cultural practice.

They are also eaten for their taste, described as being nutty and slightly sour with a crunchy texture when eaten cooked or dried.

In certain regions, beekeepers routinely remove portions of a hives’ drone brood in order to manage the growth of a harmful parasitical mite that can harm the honey bee population, said the study.

“This practice makes honey bee drone brood a by-product, producing an abundant source of farmed insects with untapped potential,” wrote Professor Annette Bruun Jensen of the University of Copenhagen and her colleagues.

“The high nutritional value of honey bee larvae and pupae that can be compared to beef by its protein quality and quantity.”

The setting up of hives and beekeeping practices could also help in providing pollination services – stimulating ecological robustness and agricultural production in an area, the researchers noted.

The Western honey bees that are available for consumption in Singapore must be farmed in a controlled environment and are not allowed to be harvested from the wild, as per SFA rules.

These bees will also likely be fully processed as they are among the insects not allowed to be imported live, with the National Parks Board (NParks) having assessed them to be an invasive species.

ARE INSECTS REALLY SAFE?

SFA has developed an insect regulatory framework that establishes guidelines for businesses that intend to import, farm or process insects into food for human consumption or animal feed.

First, the insect species must be assessed to have a history of human consumption.

SFA also requires the farming and processing of insect and insect products to be free from contaminants, with the final product evaluated to be safe for consumption.

The 16 species of insects approved as food in Singapore cannot be caught from the wild.

The agency said the guidelines were developed following a “thorough scientific review” that took reference from countries and regions that have allowed the consumption of certain insects as food.

These include the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea and Thailand.

Hygiene protocols must also be closely followed.

House of Seafood CEO Francis Ng previously told CNA that his chefs have been trained to first clean the insects before toasting them in the oven. This method is then followed by the brushing of each insect “piece by piece”.

“One should purchase products from certified suppliers that provide clear labelling and information. Consumers should pay attention to shelf life and storage products in proper conditions as advised by the manufacturers,” advised Asst Prof Puniamoorthy.

Prof Chen also said that a distinction should be made between edible insects, such as grasshoppers and mealworms, and general insects such as houseflies and cockroaches.

"What SFA has approved recently are edible insects, which are farmed in a clean environment," he noted.

He advised that consumers could also ask for information on the source of edible insects, and for further details relating to the farming process, involving feedstocks and storage, as well as processing conditions.

SO WHAT DO THEY TASTE LIKE?

Based on a recent Instagram poll by CNA, more than 80 per cent of respondents were reluctant to try insects. Several commenters cited the ick factor. “This bugs me. I’ll pass,” said a netizen.

The poll accompanied a taste test video where the ikan bilis or fried anchovy component of a plate of nasi lemak was replaced with house crickets, field crickets and silkworms.

The general consensus among those who tried the insects? A few “ews”, some “good” and “not too bad” reactions, and one “ashy” – in reference to the crumbly texture. Some even went back for seconds and thirds.

When asked if cultural attitudes towards eating insects are shifting in Singapore, Asst Prof Puniamoorthy noted that there is not yet enough research done, but highlighted the definite need for sustainable and alternative sources of protein given the global food crisis and climate change concerns.

Prof Chen also emphasised that eating insects "is not new".

"In fact, insects have been a part of human diets for thousands of years across the world. The tradition has faded away in the developed world as a result of industrialisation including large-scale animal farming. This explains our general reaction in Singapore towards eating insects, curious but also fearful.

"One way to increase consumer acceptance in Singapore would be to progressively introduce them into our diet," he said, giving an example of first replacing animal proteins in processed foods with proper labelling indicating the presence of edible insects.

"Once consumers realise that there is no off odour or funny taste associated with insect proteins, there is hope that they may be more open-minded to try other ways of insect preparation, including insects in baked or fried forms."

Being a nation of foodies, the top question remains - are they tasty?

Some have compared the flavour of edible insects to seafood, while others say they can detect a hint of bitterness in certain species. Larvae have also been described as buttery and nutty. Often, deep-fried bugs provide a crunch, but not much else apart from the seasonings used.

As Singaporean taste buds get accustomed to bugs and palates expand, can insects eventually transition from novelty food to holding their own alongside much-loved local dishes like chicken rice?

“I think, at the end of the day, if the ingredients used to make a dish are nutritious and delicious … the Singaporean in me will probably queue up for it,” Asst Prof Puniamoorthy said.

Ultimately, the proof of the pudding is in the eating.