IN FOCUS: What is the road ahead for Singapore's relationship with cars?

After measures were announced in the Budget, CNA looks at how a new Additional Registration Fee tier and the charging up of Singapore's electric car policies will affect car buyers and owners.

File photo of cars during rush hour on a Singapore highway. (Photo: iStock)

SINGAPORE: People who are interested in the types of cars being driven on Singapore's roads may have noticed some changes in the past few months.

Among the hundreds of thousands of standard sedans and hatchbacks are more luxury models and electric cars, with sales figures for last year showing that there was growing demand in both categories.

They were also in the spotlight in Budget 2022, when a higher luxury car tax was announced, along with plans for even more electric vehicles (EV) charging points.

What will these developments mean for Singapore's relationship with cars? CNA looks at the road ahead.

ELECTRIC CARS: WHEN’S THE TIPPING POINT?

If you think you’ve seen more Teslas and other electric cars on the road, you are right.

Figures from the Land Transport Authority show that the total population of electric cars more than doubled from 1,217 in 2020 to 2,942 last year.

It’s still a drop in the ocean, at less than 1 per cent of the more than 600,000 cars on Singapore roads.

But momentum seems to be building towards more people thinking an electric car is a viable alternative to a petrol-powered model.

Among new car registrations last year, around 4 per cent were electric vehicles, Finance Minister Lawrence Wong shared in his Budget speech.

This may not seem like much, but compared to 0.2 per cent in 2020, it’s a 20-fold jump. And a baby step towards Singapore's goal, announced in Budget 2020, to phase out internal combustion engine vehicles by 2040.

This acceleration in electric vehicle adoption is seen worldwide, with the International Energy Agency reporting that sales of electric cars hit 6.6 million in 2021, more than tripling their market share from two years earlier.

Experts and industry observers CNA spoke to said that the tipping point for widespread adoption in Singapore may come in three to five years’ time.

Mr Alvin Seet, treasurer of the Electric Vehicles Association of Singapore, is one of the buyers who pushed up Tesla’s sales in Singapore last year to 924 vehicles, as he switched out from another electric car. In 2020, Tesla sold just 20 cars here.

It's not just Elon Musk's vehicles that are gaining in popularity. BMW sold four electrified vehicles in 2020 and 121 last year.

To meet increasing demand, BMW will launch two new fully electric cars in Singapore this year, making a total of six EV models it has here, said Mr Lars Nielsen, managing director of BMW Group Asia.

Mercedes-Benz did not reveal the number of electric vehicles it sold here, but said sales were “encouraging so far, with demand outstripping supply”. It's launching four new electric models in 2022.

WHY MORE PEOPLE BUY ELECTRIC CARS

When Mr Seet bought his first EV in 2018, there were fewer than 10 options in total, but there are dozens to choose from now, he said.

He thinks that a few factors are converging such that a car buyer in the next few years would and should consider getting a plug-in rather than a petrol vehicle.

“Singaporeans are very pragmatic. The minority of people do it for environmental reasons, (but the) majority are just looking at their wallet,” he said.

Government incentives in recent years can add up to S$45,000 of savings for EV buyers.

And incentives do play a part but Mr Seet thinks that market factors like higher fuel prices and taxes, and a greater variety of electric car models mean that demand for EVs will pick up.

“I will say that once you start to see the used car market value of petrol/diesel cars go down, you will see people start to change their minds,” he said.

“They will start thinking: ‘If I'm going to buy a petrol/diesel now, in three years, five years or however long I want to keep the car, then I can’t get good value out of it anymore.’”

Related:

Singapore University of Social Sciences’ economist Walter Theseira said that the economics have changed significantly for EVs in the last few years.

Similar to other markets, EV adoption will further accelerate in Singapore when the price gap between EVs and petrol cars gets smaller, and when EV capabilities rival or exceed those of cars with internal combustion engines, he said.

“I don't think (government) subsidies would have made a large impact without the price and performance of the EVs available in the market improving dramatically, which they have in recent years,” he said.

“What makes most analysts predict that EVs will dominate the car industry is not government subsidy or even climate change, but simply technological progress.”

He expects the majority of new vehicle sales to be electric vehicles by the middle of the decade, although currently they are more likely to be premium vehicles.

CHARGING POINTS STILL A STICKING POINT

Another factor that’s encouraging more people to consider an EV is the number and location of charging points.

Professor Subodh Mhaisalkar, executive director of the Energy Research Institute at Nanyang Technological University said that most of the EVs in operation now are likely to be in landed properties, since chargers in multi-storey car parks, Housing Board estates and condos are not prevalent yet.

But this is changing. The Government has been building more charging points in HDB car parks, and the authorities are to build 60,000 electric vehicle charging points across the country by 2030.

In Budget 2022, Mr Wong also said that more EV charging points will be built closer to where people live.

“Charging points are clearly the bottleneck – both at work and also at home,” said Prof Mhaisalkar. He also thinks the tipping point is likely to be 2025 when EV prices come down.

“We have a unique opportunity being a city-state, where infrastructure is great and driving distances are less than 50km per day to switch entirely to EVs over the next two decades.”

This would result in a more than 40 per cent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions for all vehicle types, he estimates.

LUXURY CAR TAX NOT "A SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE"

Raj, 39, is looking to buy a new car after selling his Maserati recently, but the new luxury car tax is not a big concern.

He expects that a car with an open market value (OMV) of S$80,000 to S$100,000, which he may get, would now cost a few thousand dollars more.

“I don't see a significant difference, because that can be also given as a discount by the car dealer eventually,” said Raj, who did not want to give his full name.

A car with an OMV of S$100,000 would end up costing the buyer S$300,000 to S$400,000. Those most affected would be super luxury cars that are now selling for more than S$500,000, said Raj.

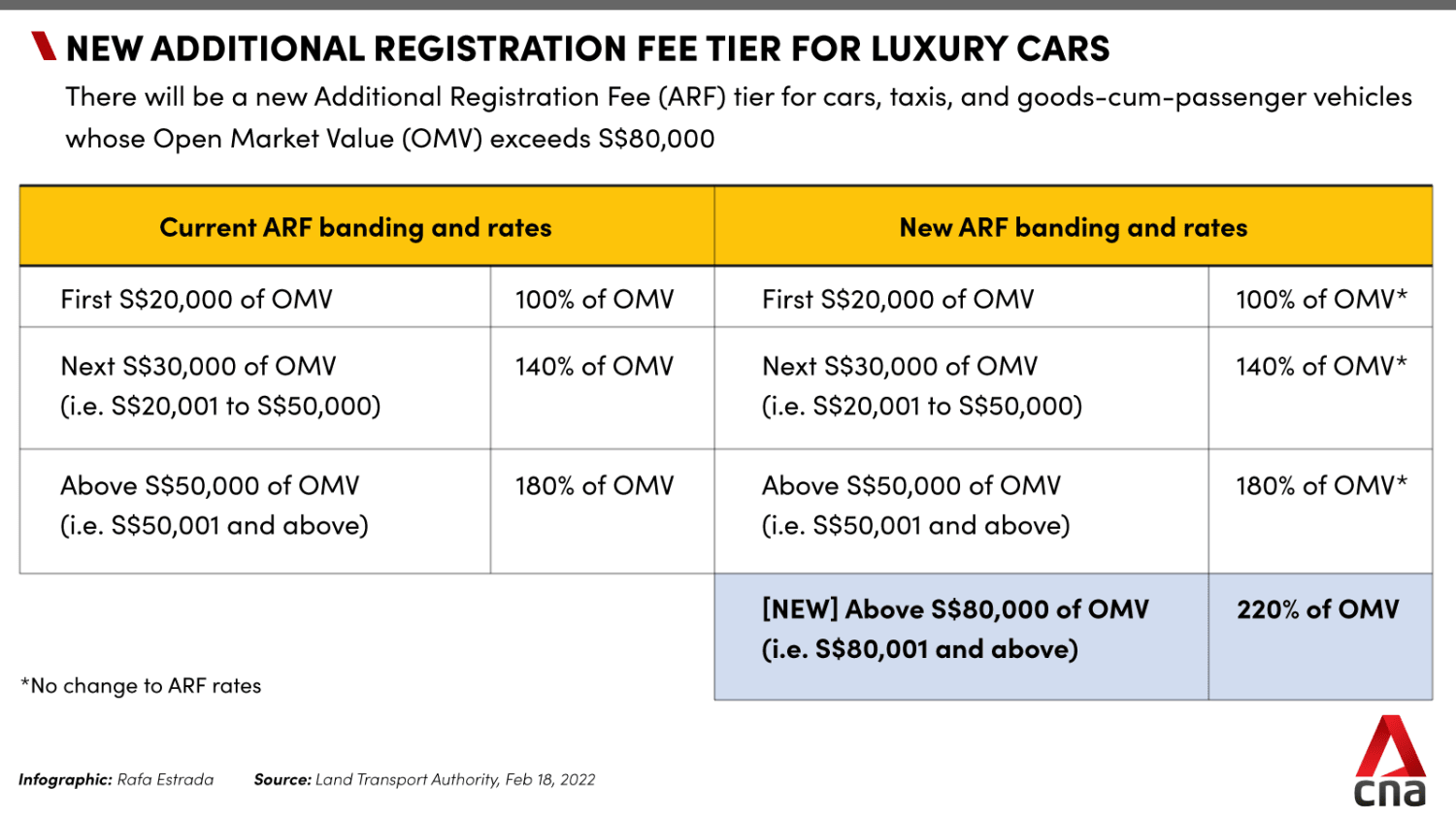

On Feb 18, the Finance Minister announced that there would be a new Additional Registration Fee (ARF) tier for cars.

The 220 per cent rate would apply to the portion of the car’s OMV in excess of S$80,000. This is up from 180 per cent, which applied to OMVs above S$50,000.

The new rates will apply to all cars registered with Certificates of Entitlement (COEs) obtained from the second bidding round this month, which concluded on Feb 23.

The new ARF tier is expected to generate an additional S$50 million in revenue per year, said Mr Wong.

With the change, there will now be four ARF tiers. For the first S$20,000, car buyers pay an ARF of 100 per cent, which means there’s no additional cost on top of the car’s OMV.

For the next S$30,000 of OMV, up to S$50,000, the ARF rate is 140 per cent, and from S$50,000 to S$80,000 of OMV, the rate is 180 per cent. For any amount above that, the buyer has to pay 220 per cent.

To illustrate, of 218 models of registered cars in a Land Transport Authority list, just over 20 models have an OMV of more than S$80,000.

From January prices, a family car like a Toyota Vios had an average OMV of S$13,919 and the ARF is the same as the OMV. It was priced at more than S$110,000 after adding the COE cost, and other fees and taxes.

A BMW 730 SR Adaptive had an average OMV of S$91,246, and an ARF of S$136,243. With the new ARF tier, it will have an ARF of S$140,741, which is S$4,498 more. It was priced by distributors at more than S$461,000 in January.

A luxury limousine like a Bentley Flying Spur V8’s average OMV was S$227,809, with an ARF of S$382,057. The new ARF will be S$441,180, jumping by S$59,123.

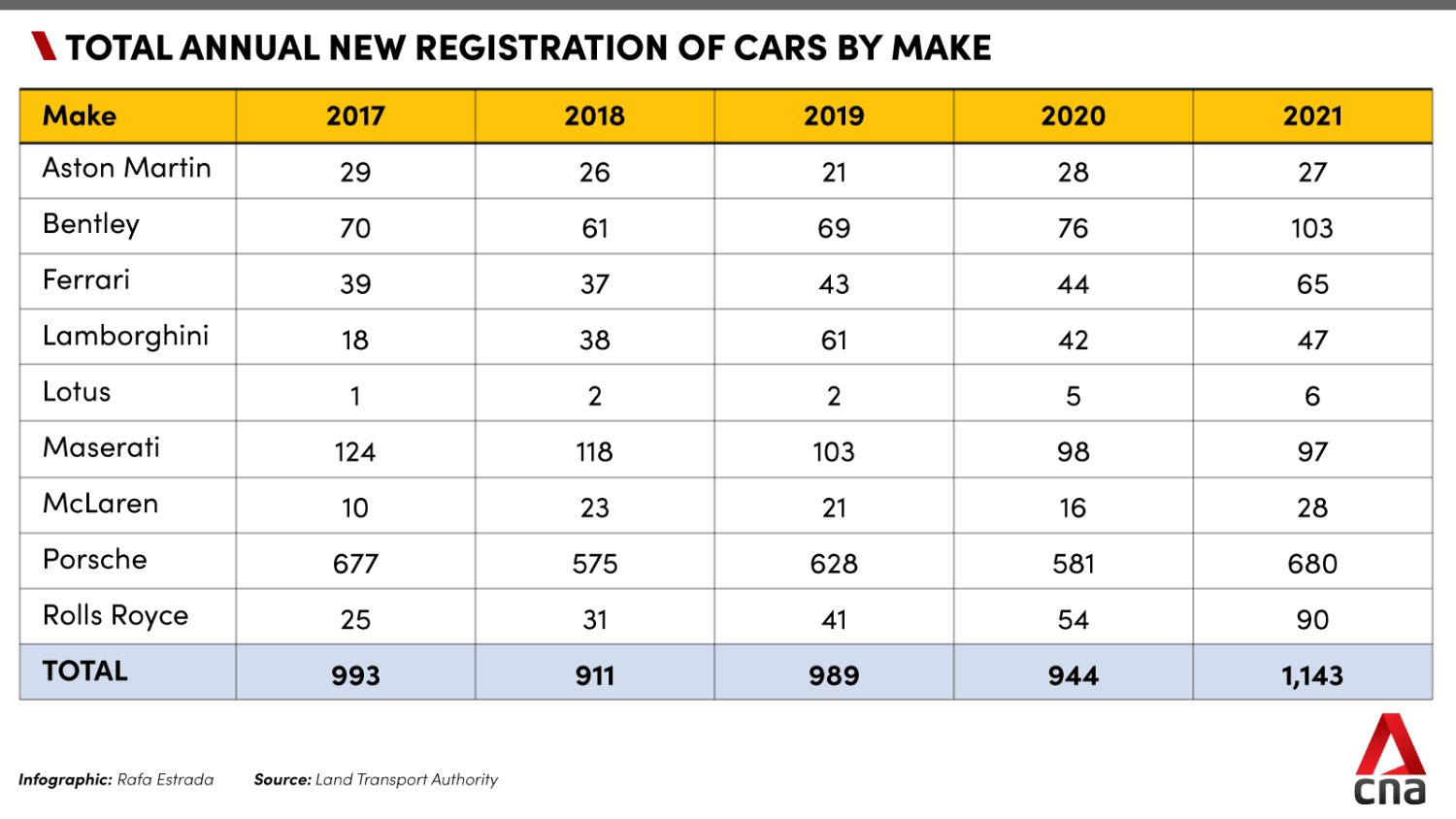

On the whole, the new tax will affect a small percentage of car buyers here, industry insiders said. Last year, the number of cars sold by luxury marques like Ferrari and Rolls Royce was 1,143 – and this was the highest in five years.

There’s no breakdown of sales for high-end models from carmakers with high-end as well as mainstream models, but BMW’s Mr Nielsen said that about 15 per cent of BMW model variants are affected by the new ARF tier.

Some car dealers and makers declined to comment or did not respond to queries on this.

It’s clear that the proposed tax has not dented demand for cars in general when one looks at the COE prices posted on Feb 23, when COE prices for bigger cars hit a nine-year high.

Mr Raymond Tang of the Singapore Vehicle Traders’ Association said that this was mainly because the quota for cars was relatively small, and demand exceeded the available quota this round.

“The reason is that in Cat B, there are still a lot of other cars that are not affected by the 220 per cent ARF,” he said.

He thinks that the increase in sales of luxury vehicles in 2021 was because wealthy people had moved to Singapore from other parts of the world, and fewer people were travelling due to the pandemic. They then spent their cash on cars, said Mr Tang.

Mr Neo Tiam Ting, president of the Automobile Importers and Exporters Association, pointed to the fact that Singapore now has zero growth in its car population, thus limiting the number of new COEs to the number of cars that were deregistered.

But as car and COE prices shoot up, more people will hang on to their cars for five or 10 more years, reducing the number of cars deregistered. He agrees that the new ARF will not have a large effect.

Mr Neo feels that some supercars are bought as a status symbol, but they are “hardly used”. He hopes that more COEs can go to people who need cars for daily use.

“If this new implementation can stop them from buying (luxury cars), then quota can be given to the people who really need the car,” he said.

Assoc Prof Theseira said some economists call luxury car taxes “an ideal tax” as “it doesn't even harm some buyers of these cars, who now can show off their financial success even more easily than before”.

“We have to realise that in Singapore's context, car ownership signals financial status very effectively – because most observers know instantly just how expensive that car is likely to be,” he said.

“So in that context, an additional tax on car ownership does not necessarily reduce demand for such high-end cars if that tax is not too high. Instead, the tax just adds to the status value of the car.”