'It's not easy being an investigator here': Police reveal finer details of dealing with serious sex crimes

Police officers investigating a mock-up sexual crime scene. (Photo: CNA/Try Sutrisno Foo)

SINGAPORE: On the 17th floor of the Police Cantonment Complex is a room with sprawling views of Chinatown and nearby Pearl's Hill City Park. There is a children's play area with picture books, toys and a little picnic table.

Within that space is another smaller room, this one windowless but with blue couches, snacks and beverages. There are purple flowers on the table and more children's toys. The atmosphere is comforting and benign, but the words being uttered in the room are anything but.

This room is where police officers speak to children who have been sexually abused. But this time, a woman is about to tell a female officer that she had been raped by a man she met on a dating app. The sexual assault took place the night before in his bedroom, the woman says.

This hypothetical scenario was part of an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at how the police's Serious Sexual Crime Branch (SSCB) investigates such cases. On Dec 8, CNA was given a glimpse of the entire investigative process, from when a report is made to when the case enters the courts.

The SSCB usually takes up sexual crimes that are tried in the High Court, including sexual assault by penetration and rape. Investigations are long-drawn, as officers must put in a lot of work to build a case that can be successfully prosecuted.

In some of these cases, evidence is scant and revolve heavily around the accounts of the victim and accused. Others involve sexual assault within the family, with victims understandably reluctant to offer the full details.

The way the police handle sexual assault victims is also in the spotlight.

Former MP Raeesah Khan claimed in Parliament that she had accompanied a rape victim to a police station to make a report, and that the victim had come out crying because an officer made comments about her dressing.

The police said it had invested "significant" resources in investigating Ms Khan's claims. She later admitted that she lied, after which a complaint was filed against her, which is now before the Committee of Privileges.

The Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) has previously called for improvements to victim interviewing, including using a standardised vocabulary and providing important context when asking sensitive questions.

The gender equality advocacy group has also suggested having designated specialist police stations to deal with sexual assault reports, where all officers are trained to deal with such cases.

Assistant Superintendent of Police (ASP) Sirikanda Chiu told CNA it is necessary to ask victims what could be seen as intrusive questions – like what they wore during the assault – to help officers match their accounts to CCTV footage or other circumstantial evidence.

"Other questions like their sexual history are necessary because they can help us understand the reports we receive from the forensic medical examination," said ASP Chiu, who is 30 and has been with the SSCB for two years.

"The victim's relationship with the perpetrator is also important, so that we know the facts and circumstances that led to the incident."

Officers are also trained to pay close attention to victims' emotions so they are not re-traumatised during interviews, she added.

INTERVIEWING VICTIMS

Back at the Police Cantonment Complex, the interview between ASP Chiu and Clarissa, the fictitious victim, is about to begin.

Either male or female officers could be assigned to interview victims, depending on manpower availability. But if the victim prefers to be interviewed by an officer of the same gender, arrangements will be made.

Before starting the interview, ASP Chiu offers Clarissa bottled water and a jacket. Victims always get cold in this room, she says. The victim can also ask questions or go for toilet breaks at any time.

"The interview will take quite a while, because we need to ask you questions in detail," ASP Chiu tells Clarissa in a steady and soothing voice, gently patting Clarissa on her arm.

"Along the way, some of the questions may be intrusive and you might feel slightly uncomfortable with the questions. But do bear with us, because these are necessary for us to verify. So I hope you do not mind."

If a victim is not comfortable sharing certain details, ASP Chiu said she will reassure them that the investigation is confidential. She added that officers are trained to ask questions tactfully.

"My personal experience is helping the victims to recount what happened to them, especially sexual assault cases, is difficult and painful. It's actually very traumatising and emotional for them because they have to relive the incident over again, just to share their account with you," she said.

"I cannot say that I understand their situation. But I do seek to acknowledge their feelings and experiences by lending a listening ear, and assuring them that the investigation is fair and we will deliver justice."

ASP Chiu explained that officers who deal with sexual crimes go through a victim management course conducted by the Home Team School of Criminal Investigation. Specialists from the Police Psychological Services Department also teach officers victim care techniques.

"Sometimes, victims just want a listening ear. So, we would do that most of the time, because we would want to try to understand their concerns and worries in this investigation process, and then we will address them accordingly as well," she added.

Nevertheless, ASP Chiu said some victims still find it tough recounting the assault. She recalled her first intra-familial case of sexual crime, involving a man who sexually assaulted his daughters.

"I faced a lot of challenges in getting the victim to recount, and this time round we're not just talking about one victim," she said.

This is a challenge that ASP Mohammad Amin Majid, who is in charge of a team of five investigators in the SSCB, has faced before.

In one of his cases, a female victim had been sexually assaulted by her father since she was three years old, but withheld certain details in the initial interview.

"It was very difficult for her to open up, because at the back of her head, if she opens up about what has happened, she knows she's going to tear her family apart," the 33-year-old said.

Building a relationship with the victim is important, said ASP Amin. It took constant communication, patience and a few days before the victim finally opened up.

"I applaud her courage. That goes to all victims of sexual crime who actually take the first step forward to report a case to the police or the relevant authorities, despite them going through a traumatic experience," he said.

Officers also have to deal with their own feelings.

"I have to remind myself to remain composed, impartial and of course objective in my investigation, as much as there are a lot of emotions involved in the cases," ASP Chiu said.

MEDICAL EXAMINATION

Clarissa eventually reveals she had been with "John", the alleged perpetrator, the night before in his home. She woke up realising she had been raped, but discovered that he had left the house. She called the police.

The next step for Clarissa is to undergo a medical examination in the same complex, where she will be attended to by doctors from public hospitals.

This is part of a one-stop concept that allows victims who have been interviewed to undergo forensic and medical examinations in the same place. Previously, they would be escorted to a hospital by officers.

"It actually brings about convenience and privacy to the victim," ASP Chiu said.

The medical examination area is a rather small room on the same floor. It has a reception section with a table and chair, and a larger space with medical equipment and an examination table.

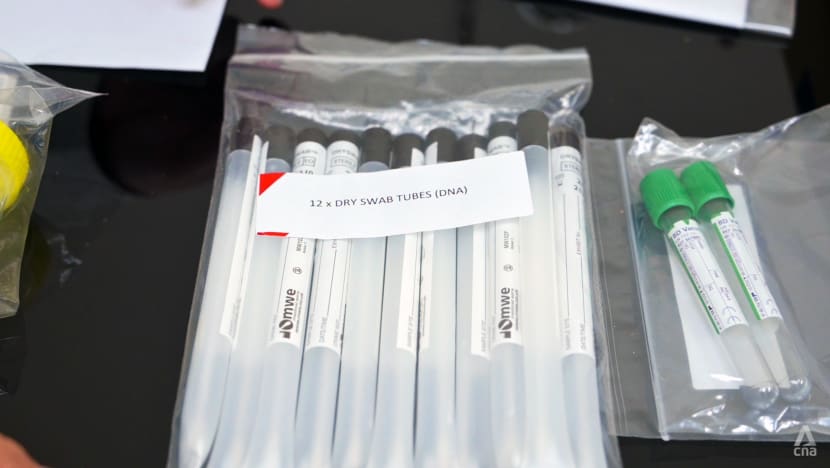

On the table is a sexual assault examination kit, more commonly known as a rape kit, containing brown envelopes and tubes of various sizes. It is used to collect physical evidence from victims who have been assaulted within the last 72 hours.

During the exam, victims are asked to take their clothes off while standing on a piece of brown paper, to collect trace evidence like pubic hair.

If the victim is still wearing the same clothes as during the assault, these will be taken by investigators and kept in separate envelopes. Extra clothing like disposable undergarments is provided to the victim.

Doctors then swab the victim in various genital areas and may take urine or blood samples for DNA and toxicology tests. These samples and clothing are sent to the Health Sciences Authority for analysis.

Once the doctors are done, the room will be thoroughly cleaned to remove any traces that could contaminate the next medical examination.

THE HUNT IS ON

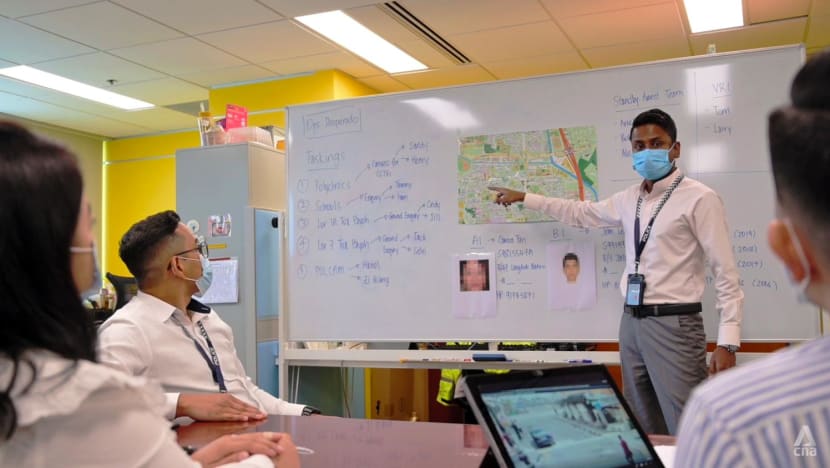

In another briefing room on the 17th floor, the hunt for John is on.

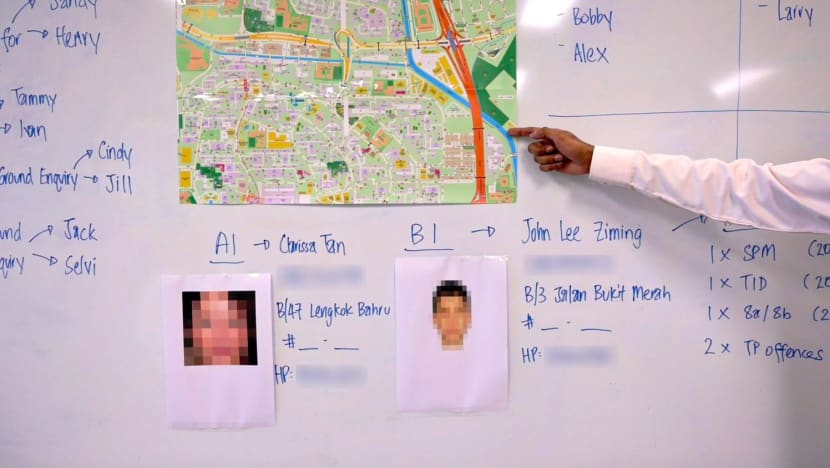

ASP Amin and ASP Chiu gather with other colleagues from the SSCB. The room is messy with makeshift cubicles, and a giant whiteboard stands in the middle. Details about John have been scribbled on it, including his mobile number, address and NRIC number.

As the leader, ASP Amin takes charge of the briefing. He speaks in a firm and sharp voice, assigning tasks to officers.

One team will scour the coffee shops that John frequents. Another will look out for police cameras and private CCTVs in the vicinity, to trace John's route before and after the incident. A separate team will be on standby to move in for the arrest.

John also has a history of drug offences, so officers should be armed, a team member points out. ASP Amin agrees: "I do not know whether he knows that we are looking for him. But just be on guard."

ASP Chiu chimes in – based on her interview with Clarissa, John was wearing a blue T-shirt and dark-coloured pants when he left the house. ASP Amin tells field investigation officer Station Inspector (SI) Li Junqi to take note.

SI Li, 36, has been with the SSCB for slightly more than two years. His task in this case is to trawl through CCTV footage in search of John.

"Of course, we don't have footage for an incident that happened behind closed doors, but we look for footage before and after the alleged incident to look more into the behaviour and demeanour of the involved parties," SI Li told CNA.

This includes details like whether the victim was distressed or injured before or after the incident, or whether the accused was acting suspiciously or showed signs of having been in a dispute.

The footage can also corroborate where the incident took place, and help officers uncover the facts and circumstances of a case, especially when they are working with conflicting accounts and little evidence.

SI Li remembers one case where a man picked up a drunk woman by the roadside and sexually assaulted her at a nearby HDB block. They were not known to each other.

Officers found the suspect's vehicle on police camera and CCTV footage and traced it to his residence. They set up an ambush at the car park and arrested him.

Officers may also speak to the victim's family members and friends, as well as potential eyewitnesses who were near the incident's location at the time.

"Even though we don't have CCTV footage, we will also tap on forensic evidence, such as having the victim and accused undergo forensic medical examination for traces of DNA and also injuries," SI Li said.

"What is crucial is also both their accounts – whether they are corroborative to the case."

When officers have traced the suspect, it is up to them when to move in. "All serious sexual offences are arrestable offences under the Criminal Procedure Code," SI Li said. "Depending on facts and circumstances, it is based on our discretion to go for the arrest."

ACCUSED BROUGHT IN

Officers soon find John and bring him in. Suspects may be subjected to a medical examination – and may receive medical treatment or be taken to a hospital if necessary – before sitting through a video-recorded interview.

Since September 2018, interviews with those accused of serious sexual crimes must be video recorded. This helps the courts decide on allegations that could be raised about how the interview was conducted. The requirement will eventually apply to all suspects.

This interview room looks nothing like the room where the victim was interviewed.

It is much smaller, with grey soundproofing material lining the walls and a screen separating the suspect from police officers. A bulbous camera hangs above, piping live images to a screen near the door.

John is seated before two officers, his right hand cuffed to a metal bar. The officers tell him they are investigating a case of rape, and ask if he has any issues with a video-recorded interview – he says no. The officers then ask if he has eaten or is under any medication.

As the interview progresses, it becomes clear that John is trying to paint a picture of consensual sex.

He says he asked Clarissa in the living room if she wanted to have sex, but stopped when she said no. When they moved to the bedroom, John says Clarissa started touching him.

"She took off her own clothes," he says. "Then I think we had the feeling, so we decided to move into sex."

RETURNING TO THE SCENE

With a conflicting narrative developing, the police have to return to the incident scene and try to find additional evidence.

This is the job of Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) Muhammad Jamil Agus Rizal, 33.

The senior investigating officer, who has been with the SSCB for about two years, said evidence from the scene is gathered and can be produced in court to contradict or support the accounts of those involved in the case.

In John's bedroom, DSP Jamil slips on gloves and shoe covers. He checks a dustbin, where he discovers a used condom. This has to be seized, he tells a pair of crime scene specialists.

As John has not returned home since the incident with Clarissa, the scene is relatively untouched. On his bed, his blanket and underwear lie in a heap. Used pieces of tissue are scattered on the floor. An unused condom packet is under the bed.

The crime scene specialists use white placards to number the evidence before taking photos. John's underwear is wrapped in a piece of brown paper and placed in a tamper-proof evidence bag. This and other evidence will be sent to the Health Sciences Authority for analysis.

Officers also seize John's laptop. Digital evidence like this could show the communication between the victim and accused in the lead up to the incident, as well as photos and videos related to the incident.

The investigation goes into far more minute details. One of the crime scene specialists shines a white light on the bed and points out specks of fibre that did not match the colour of the bedsheet. These could be from Clarissa's clothing.

Specialists may also use a blue light to reveal biological fluid stains and swab the area to get a sample.

"What investigating officers look for at crime scenes will depend on the facts and circumstances of the case," DSP Jamil said. "It could be pieces of clothing, it could be DNA evidence, such as biological fluids. It could be condoms, sex toys or lubricants."

Depending on the case, the victim or accused could be brought back to the scene to help police uncover more evidence.

"Where possible, we are very mindful of the victims' emotions, and we do not want to re-traumatise the victims as far as we can," DSP Jamil said.

"But it may be necessary ... so that police can have a better appreciation of what actually happened. This is especially important for cases where there are no direct evidence, witnesses or CCTV footage. This is not uncommon for sexual crimes."

In cases involving intra-familial sexual abuse, a crime scene visit by the accused could quickly turn ugly, and SI Li said officers must handle the case "with extra care and sensitivity".

"When we do have the accused meeting the family members, it's always more emotional," he added. "We have to ensure that the situation is under control. We must remain firm and calm in handling them."

Another challenge in processing sexual crime scenes is how long later a report is lodged.

"For cases that are reported some time after it happened, it will be a challenge for the police to gather direct evidence," DSP Jamil explained, pointing out that evidence like DNA as well as drugs and alcohol in the body degrade quickly.

"Therefore, there is a need to preserve the scene as soon as possible, and ideally, for the victims to step forward and report the crime early."

But even if a sexual crime was reported late and the scene has been cleaned up, the police could still go back.

"Depending on what the victims or the accused tell us, there may still be value for us to visit the crime scene," DSP Jamil added. "We will do our best to look for evidence that may still be related to the case."

PREPARING FOR PROSECUTION

ASP Amin said the police will investigate every sexual crime case regardless of how late it was reported, as he acknowledged the trauma that victims could go through in the immediate aftermath of the incident.

"It does not matter (when the incident was reported)," he said. "We will still investigate the case wholly. We will look at other evidence as well as the versions from the victim and accused."

For cases that have little objective evidence, ASP Amin said the police will rely on comprehensive accounts from those involved in the case, and work with the Attorney-General's Chambers (AGC) to decide if the case can be prosecuted.

"We will lump all these accounts together and look at a case wholly and objectively," he said, adding that for the prosecution to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt, the victim's testimony needs to be "unusually convincing".

"From the victim's account, we can really verify that it is because of this, this has happened or whatsoever. It's not just words against words; we go into detail."

Ultimately, ASP Amin said the branch looks at cases wholly and objectively with no bias "at all".

"Sometimes when we run a case, there is no wrong answer. It's open to opinions and open to how people think about it. Even the deputy head or the head of the branch will give guidance as to whether this case can be prosecuted or not," he added.

The police will then discuss their decision with AGC, while prosecutors can interview the victims to understand their version of events and run through the facts again.

If AGC is confident that the case can withstand the courts' scrutiny, the accused will be prosecuted. And if the accused does not plead guilty, ASP Amin and his colleagues must start preparing for trial.

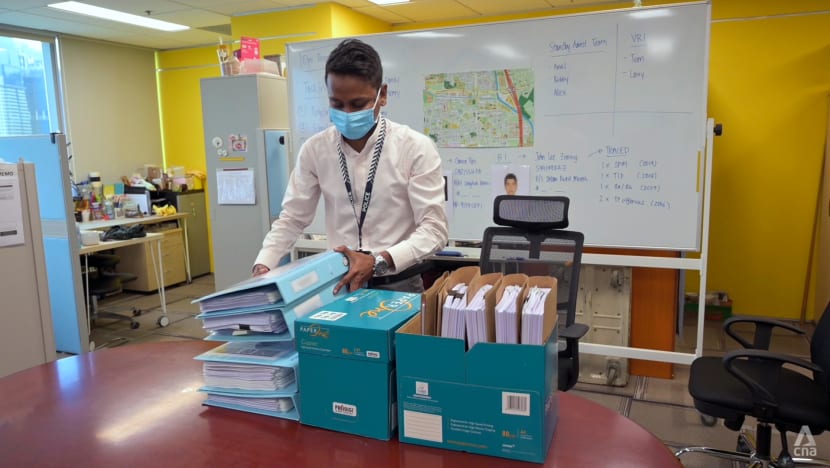

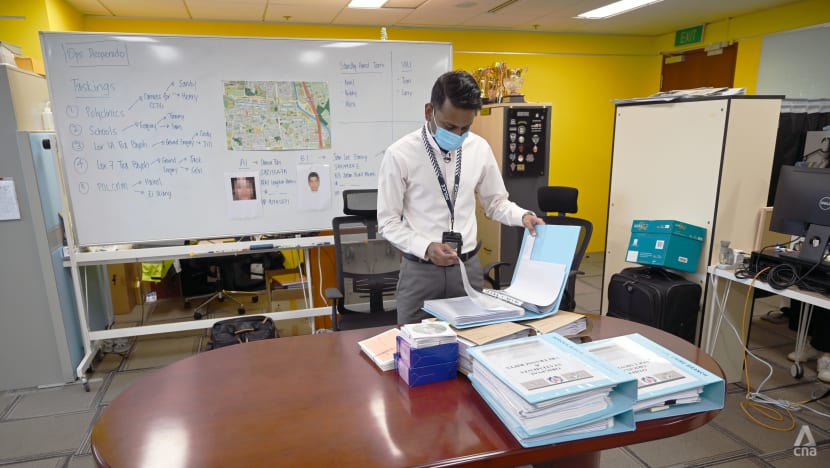

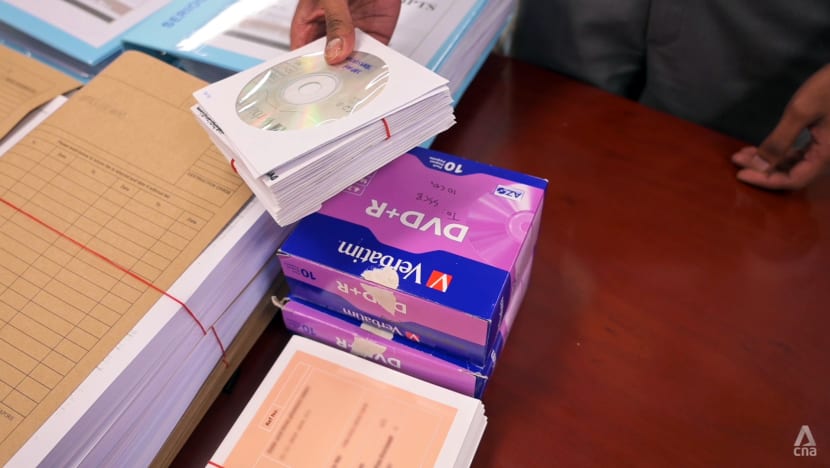

Back at the briefing room, ASP Amin walks in lugging a large suitcase filled with boxes of files, folders, photographs and computer discs. This overwhelming bundle, called the case for prosecution, is only for one case, he says.

The bundle contains hundreds of pages of conditioned statements from victims and witnesses, a list of exhibits, as well as a list of witnesses. The discs contain video-recorded interviews of the accused and CCTV footage.

Conditioned statements are original statements repackaged to a particular format. These statements will be vetted by prosecutors and signed by those who gave them. Only conditioned statements can be tendered in the High Court, ASP Amin said.

Before the trial, investigating officers will introduce prosecutors to witnesses and give a breakdown and timeline of what to expect. Witnesses are served with subpoenas to ensure they attend the trial.

Victims and witnesses will also go on familiarisation visits to the court to mentally prepare them for the actual trial.

"As you can see, it's not an overnight thing. It's a lot of effort put in and the trial may even drag on," ASP Amin said, explaining that the evidence needs to be put forth and this depends on when different parties testify or get cross-examined.

Some trials can run for three to six years if the accused chooses to appeal. "The cases are long drawn in court not because we sitting on the case," he added.

Despite that, ASP Amin believes the effort put in is worthwhile, as he described the satisfaction of getting a conviction and hopefully closure for the victims.

"To be honest, it's really worthwhile because we really make a difference," he said. "It's not that we just do our job. We will also look after the victim as well."

MIXED BAG OF FEELINGS

Still, these feelings of achievement are often tinged with those of shock and sadness, and the SSCB officers have their own way of dealing with them.

"It's not easy being an investigator here," ASP Amin said, adding that he was "appalled" when investigating intra-familial cases. "Because you really see and handle the taboo kind of cases."

SI Li said the cases he encountered while with the branch were largely different from anything he has witnessed in his 13 years in the force.

"They may be more unthinkable and also maybe shocking to society in general. It may involve close family members, and the victims may be a close party in the family," he said.

SI Li, who recently became a father, acknowledged that he was personally affected when he brought an accused to his home and saw how distraught he was that he had disappointed his mother.

"Sometimes, the victim is not just the victim specifically. But the ones who get hurt can be the entire family as well," he said.

ASP Amin said he tries not bring his work back home, pointing out that it could be "unhealthy" if officers dwell on what victims went through.

Instead, when there is a particularly traumatising case, officers of the branch check in on one another and make themselves emotionally available for each other.

"We are human beings; we will definitely get affected by their stories," DSP Jamil said. "But ultimately, we are police officers and our job is to investigate and find out the truth."