IN FOCUS: How the ease of getting prescription drugs from Telegram, multiple doctors can fuel addiction

Narratives about drug addiction in Singapore tend to focus on illegal substances. Less attention is paid to prescription medication - but addiction to it should be taken as seriously, as CNA learns.

Obtaining prescription drugs from unlicensed sources, whether a friend or an online platform, is not a new phenomenon. (Animated illustration: Rafa Estrada)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

- A paper in the Singapore Medical Journal in 2022 stated that misuse of prescription medicine was common, with prevalence "comparable" to the use of recreational drugs or novel psychoactive substances

- Taking medicine obtained from unlicensed sellers comes with risks - as does taking more than the amount prescribed by licensed sources like doctors

- One may be inclined to perceive prescription drugs as less harmful than illicit drugs, which could further enable addiction, according to counsellors

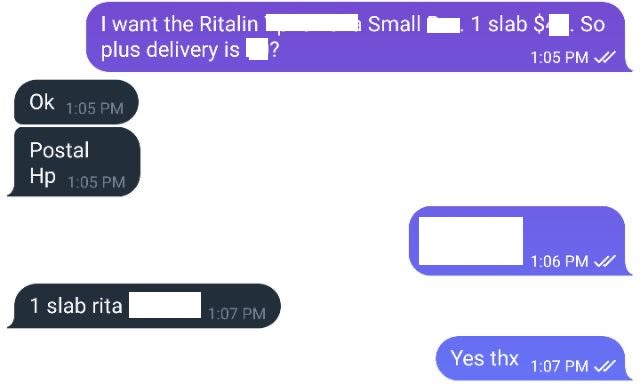

SINGAPORE: It was the most hassle-free online shopping experience.

In less than a minute, I confirmed an order for a slab of supposed "Ritalin" – a brand name for the methylphenidate stimulant used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The seller on Telegram only required my mobile number and postal code. They repeated the order and the deal was sealed.

Later that same day, I collected the package in a public car park and paid in cash. The exchange, once again, took less than a minute.

I didn't need a prescription to get a prescription drug.

After receiving a tip-off early about a channel on the Telegram messaging service selling prescription medication, I spent time just lurking and monitoring it.

Among the bevvy of medicines it claimed to sell were Ritalin, Xanax for anxiety and pain relievers like tramadol and codeine. There were photos of the products along with screenshots of reviews from customers.

The items listed in the Telegram channel are “therapeutic products”, otherwise known as pharmaceuticals. They are regulated by Singapore's Health Sciences Authority (HSA) under the Health Products Act and its regulations, including the Health Products (Therapeutic Products) Regulations 2016.

The legislation targets only sellers and suppliers. Nothing in it penalises buyers.

EASE OF ACCESS OVER COST

Obtaining prescription drugs from unlicensed sources, whether a friend or an online platform, is not a new phenomenon.

In November 2023, three men were hospitalised after suffering adverse reactions to unregistered medicines which they took to improve alertness. The drugs were bought from friends and an illegal seller.

Previous reports have highlighted seemingly enduring practices among youth who misuse “brain boosting” drugs like Ritalin and modafinil.

A Straits Times article in 2013 reported that some students faked ADHD symptoms to get Ritalin to help improve their concentration, with one claiming the practice had been going on for “at least a decade”.

In 2017, the broadsheet reported that students as young as 16 were turning to online platforms, including Telegram, to buy modafinil.

Prescription medications hawked on Telegram appeared to be much more expensive than their licensed counterparts being sold in clinics and hospitals.

In the Telegram channel I joined, a single 10mg Ritalin pill cost a whopping eight times more than it would from a private clinic in Singapore.

A similar product – dubbed a "small" version of Ritalin by the channel – was cheaper but still two-and-a-half times pricier than a 10mg Ritalin pill from a private clinic.

I couldn't understand why such prices didn’t put off buyers. But then I realised the relative simplicity and speed of procuring a prescription drug – at least from this channel – easily outweighed all else.

If someone wants to misuse such drugs and is willing to buy from an unlicensed source regardless of cost, virtually nothing is stopping them from turning to Telegram, a street peddler, a friend or any accessible avenue for that matter.

Prescription medication on e-commerce and social media sites

It is prohibited to sell any prescription medication, including medicines with addictive potential (MAPs), on local e-commerce and social media platforms, said a spokesperson for HSA.

Codeine-containing cough medicines, sedatives and opioid painkillers are considered MAPs. These can only be supplied by a doctor or a pharmacist, as they contain “potent ingredients which could lead to serious adverse effects if taken without medical supervision”.

Over the past five years, approximately 7 per cent of seizures of MAPs were from sales via messaging apps, added HSA's spokesperson.

Most were seized through enforcement action on the ground.

From 2019 to 2023, the number of online listings of MAPs “remained low”. Eight listings of codeine tablets were removed from local e-commerce platforms from January to November 2023, while no listings were detected for sedatives and opioid painkillers during the same period.

From 2019 to 2023, HSA prosecuted 38 people for selling or importing MAPs illegally. Of these, three sellers sold MAPs via Telegram, while none sold on local e-commerce platforms. The convicted individuals were sentenced to between two and 30 weeks’ imprisonment.

Anyone who illegally sells and supplies prescription medicines can be fined up to S$50,000 and/or jailed for up to two years under the Health Products Act.

PHYSICIANS A "COMMON SOURCE"

Licensed sellers and suppliers can also be a source of misused drugs.

In 2022, the Singapore Medical Council processed 39 complaints regarding excessive and/or inappropriate prescription of drugs. Of these, 15 were complaints received that year itself.

In comparison, the council received a total of 29 such complaints from 2017 to 2021.

The statutory board under the Ministry of Health governs and regulates the professional conduct and ethics of registered medical practitioners.

According to an October 2022 paper in the Singapore Medical Journal, a survey of 1,000 individuals aged 21 and above in Singapore found that misuse of prescription medicine was common, “with prevalence comparable to the use of recreational drugs or novel psychoactive substances”.

The survey, conducted back in 2015, also found that a “common source” of misused drugs was physicians.

And this hasn’t seemed to change in recent times, according to addiction counsellors who spoke to CNA.

Mr Andy Leach, director of addictions services at Visions by Promises, has seen clients who visited “eight to 10" doctors for the same medication.

The practice is called “doctor shopping”.

“None of these doctors have any way of communicating with each other as to what’s been prescribed. That’s incredibly dangerous because basically, people can overdose,” he said.

Echoing the sentiment, Mr Suresh Anantha, principal counsellor at the National Addictions Management Service with the Institute of Mental Health, said: “Patients abusing prescription drugs might present to their physicians as seeking help for health issues and illnesses. They might even visit various physicians to obtain multiple dosages of the prescription drugs.”

This contributes to the challenge of detecting patients who misuse prescription drugs, he noted.

With practising doctors, the Singapore Medical Council has guidelines governing various medication prescriptions.

For example, benzodiazepines – a class of depressant drugs that can be highly addictive – are supposed to be prescribed for either intermittent use or short-term relief between two to four weeks.

Doctors are also required to limit chronic benzodiazepine prescriptions where possible. When repeatedly prescribed, doctors must clearly document their justification along with a comprehensive assessment of the patient, their diagnosis and their psychosocial history.

CNA has contacted the Health Ministry about their stance on “doctor shopping” and whether there are measures against such behaviour across the public and private sectors.

At Visions, the addictions treatment arm of Promises Healthcare, the prescription drugs that Mr Leach’s clients tend to be in recovery for include codeine, benzodiazepines like Valium and Xanax, painkillers like Lyrica and tramadol, and sleeping pills.

Mr Leach estimated that 33 per cent of the clinic's outpatients were receiving treatment for an addiction to prescription medication.

“From what I’ve seen ... whether it’s prescription medication or any other form of addiction, it’s been escalated by the pandemic,” he shared.

"The element is the lack of stimulation ... people being in close quarters with (each other), family tensions, stresses. It's very stressful to stay locked up in a house or an apartment consistently, (with the) lack of connection, lack of the ability to go and do your normal things."

Asked why she had co-authored the Singapore Medical Journal paper on the misuse of prescription medicine, Dr Chan Wui Ling said the team wanted to study its significance in the Asia-Pacific region. Most published data on the topic was about Western countries.

“Generally, we have encountered patients with addiction issues during our clinical work, but there is no published data on prevalence rates,” added the senior consultant in the emergency department of Khoo Teck Puat Hospital.

FROM TREATMENT TO ADDICTION

Such a patient might resemble T, a recovering addict who spoke to CNA on condition of anonymity.

The woman, now in her 50s, once kept a “rotating list” of clinics to visit every month and estimates having been to at least 30 different ones to get medication.

Like many others, her addiction began with a legitimate prescription. At 23, she was prescribed benzodiazepines, a class of drugs often given to treat anxiety. Hers was so severe that she used to collapse from panic attacks.

With what she described as a history of addiction in her family, it wasn’t long before she was hooked - and further enabled by how easy it seemed to get benzodiazepines from doctors.

Let’s put it this way, I could get whatever I needed. They would give it to me, even though it was way over the amount of what I should be taking."

Then came tramadol – a strong opioid painkiller which T was prescribed 15 years ago, after suffering three slipped discs in her lower spine.

Beyond numbing the physical pain, it “shut everything down”, she said, including the pain from past trauma in her life.

She was instructed to take one 50mg capsule, thrice a day – but was soon popping more than 10 times the prescribed amount.

Her tramadol supply always came from “legitimate sources”: After all, she had genuine scans of her slipped discs and was skinny and fragile in appearance, thanks to her full-blown addiction at the time.

"I think when any doctor saw someone like me, I was very much an actress where I was being very manipulative (to get the medication I needed),” she explained.

Mr Leach pointed out that people cross the line into addiction when their original, presenting problems seem to be dissipating – yet they become “unable” to stop taking the drugs due to withdrawal symptoms.

And their initial problems, such as pain or anxiety, tend to come back worse as they wean themselves off the medication.

“The other thing that can happen is that you find yourself taking more (of the medication) because you develop a tolerance,” he added.

“MAKES MORE SENSE TO STOP SUPPLY"

T never purchased her benzodiazepines or tramadol via online channels. She didn’t want to risk getting “something that could be deadly” – and she also assumed buying from such places was illegal.

Reflecting on her addiction spanning over two decades, she believes penalising buyers – including those like her who turn to “legitimate sources” – would have “100 per cent” helped to end the nightmare.

“There were days where I’d sit there and think, ‘I can just get an extra whatever and feel better today and I don’t have to feel like this.’

"It definitely fuels the addiction because you know you can get these things,” she recalled.

“If there were laws where I was cut off and I knew I would never be able to get these things (easily) … it would maybe save a lot of people from getting into the situation that I did.”

When asked, HSA did not specify why there was no legislation penalising those who buy prescription drugs from unlicensed sources.

Seasoned litigator Christopher Chong, who has defended hospitals and medical practitioners in medical negligence suits, did not have insight into the rationale behind the legislation either. But he suspects it could be due to enforcement difficulties against individual buyers.

The senior partner at Dentons Rodyk and Davidson noted that while there was no defence or reason for an individual to possess Class A narcotics, there can be a valid reason for possessing a prescription medication.

“It then makes more sense and (is) also more efficacious to try to stop the supply of the medication at the source.”

Mr Shashi Nathan, a partner at Withers KhattarWong heading the criminal litigation practice, added that the key exception might be when someone cannot provide “a reasonable explanation” for buying prescription drugs in bulk.

“It could well lead to a separate investigation (on) whether you are buying for the purposes of resupply. That would make you a seller,” he said.

PRESCRIPTION DRUG ADDICTION "MORE DANGEROUS"?

Under the Health Products Act, anyone who illegally sells and supplies prescription medicines can be fined up to S$50,000, jailed for up to two years, or both.

But it isn’t simply an absence of penalty for buyers or the ease of getting prescription drugs that could enable addiction to them.

Counsellors also pointed out that Singapore’s zero-tolerance approach against drugs, with its focus on illicit substances, may inadvertently shape the perception of what is “more acceptable”.

“One might perceive prescription drugs as being less harmful than illicit drugs because they are available at clinics and thus not illegal. Nor will they be subjected to criminal prosecution for using it,” explained Mr Anantha from IMH.

“Or (they may perceive) that these drugs are not harmful because they are prescribed by physicians for legitimate health problems, such as pain, insomnia and anxiety.”

Authorities have previously imposed more stringent measures to curb the abuse of a prescription drug. In 2006, buprenorphine, the active ingredient in Subutex, was made a Class A Controlled Drug under the First Schedule of the Misuse of Drugs Act. This means the importation, distribution, possession and consumption of Subutex was made an offence unless specifically exempted by relevant authorities.

Subutex had been approved for use in 2000 by the Ministry of Health and introduced in 2002 as a substitution treatment for opiate-dependent drug abusers, but drug addicts were found to be abusing it.

Mr Leach believes an addiction to prescription medication is equally if not "sometimes more dangerous" than being hooked on illicit drugs.

For instance, he has seen clients in and outside Singapore for addiction to opioids, which include illegal drugs such as heroin and fentanyl but also prescription painkillers like tramadol.

“An opioid addiction, whether it comes in a pill from a doctor or a street dealer in the form of heroin or fentanyl, is identical in terms of the impact it has on the individual,” he said.

The difference in how we regard each addiction has definitely to do with perception. But in reality, you’re looking at the same problem.”

The brain “doesn’t distinguish” between heroin and prescription opioids, or between drugs that are used medicinally and recreationally. The potential for abuse and developing a substance use disorder is the same for both prescription drugs and illicit drugs, echoed Mr Anantha.

While a legal deterrent may help some recovering addicts, Mr Leach also noted that someone with “active addiction” wouldn’t care.

They would have reached the point where getting the medication is a matter of survival, and can be "very manipulative, intentionally or subconsciously”, to get what they want.

When an active addict doesn’t get their way, they “may come across as depressed or anxious” due to withdrawal, he added.

It is hence "very easy to misdiagnose an addict” and inadvertently prescribe them medication that may enable an ongoing addiction.

AN ADDICTION-CENTRED APPROACH

The fight against the misuse of prescription drugs ultimately boils down to doctors having awareness around addiction, Mr Leach believes.

They must ask the right questions: How long have you been taking this medication? What's it for? Where were you first prescribed it? Who made the initial diagnosis?

“I can tell if someone is seeking medication or whether it’s a genuine need," he said.

"The fact is for anyone in active addiction, it will create problems in their lives. You start seeing unmanageability. It will impact their work, finances, emotional well-being, mental health, family, all areas of life.

"People start to appear more isolated, less connected, more reliant on the medication," he added.

"To a professional eye, someone who works with addiction, it’s pretty obvious what’s going on.”

When Mr Leach refers his clients to psychiatrists within Promises, they spend at least an hour speaking with the client before diagnosing and prescribing. They may also follow up with previous clinicians who have made the same diagnosis.

Medical professionals like Dr Chan, who co-authored the paper in the Singapore Medical Journal, also have several ways to spot possible addiction.

This includes a thorough medical consultation to determine the patient’s reasons and concerns for the doctor’s visit, she said.

Doctors also observe the patient's frequency of medicine use "to suggest possible dependency", and look out for repeated medical visits for similar medication within a short period of time.

Doctors will advise patients on the use of prescribed medication, and warn them of potential side effects and/or risk of dependency, she added.

IN RECOVERY

If T hadn’t sought help when she did, she may not be alive today.

In fact, for a while, she was “almost okay” with death, she admitted. The one saving grace was the thought that her children could one day find her dead if she didn’t stop her addiction, and that they would have to live with that for the rest of their lives.

After about a year in recovery, she is now a “totally different” person. While still on benzodiazepines, she takes it as prescribed – and without the weight of shame.

She recalled going for a swim during an initial period after going cold turkey. After a few laps, she paused to look up at the surrounding trees framing the sky and buildings.

“I just had this feeling inside me. It was the first time I felt this emotion of ‘wow, look how beautiful everything is’," she said.

“It was just such a wonderful feeling, like I could actually appreciate the trees and the smell of fresh air and even the birds.

"Everything just came back to me from when I was young, doing all the things that I used to love.”

As much as the addiction took from her, T believes she needed to go through "all that" to get to where she is today. Life is now easy in ways it never was. It's as simple as waking up in the morning and looking forward to the day, she said.

After all, it was not too long ago that an uncomplicated life meant something different.

One day, you're manipulating doctors with a performance that comes too naturally. The next, you've lost two decades to addiction. It is easy to fool yourself into thinking something is "more acceptable" because it's not illegal.

In my experience, it sometimes takes less than a minute.