As secondary schools tighten smartphone use, parents say students can still outsmart the rules

Some parents say students already hide devices or bring dummy phones, while teachers point to limited manpower for policing usage.

Secondary 2 students in a mathematics lesson in their subject-level class. (File photo: CNA/Raydza Rahman)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: When his younger daughter began showing signs of smartphone addiction, Mr Aylwin Lam, 48, spent months attempting to wean her off her device.

It was not easy – the Primary 5 student would sometimes fly into a rage when asked to put her phone away. Her school had already raised concerns to Mr Lam about her experiencing issues with her classmates and displaying other behavioural problems.

But with persistent effort from Mr Lam and his wife, their daughter gradually reduced her smartphone usage, cutting her daily YouTube sessions from two to three hours down to just 15 minutes.

“It was quite scary because you don’t realise it until it’s too late … Since I personally experienced it, I hope that all parents should really ban handphone usage for their kids,” said Mr Lam, who also has a daughter in Secondary 1.

Mr Lam's experience underlines why many parents are welcoming the Ministry of Education's (MOE) latest move on Nov 30 to further restrict smartphone and smartwatch use in schools.

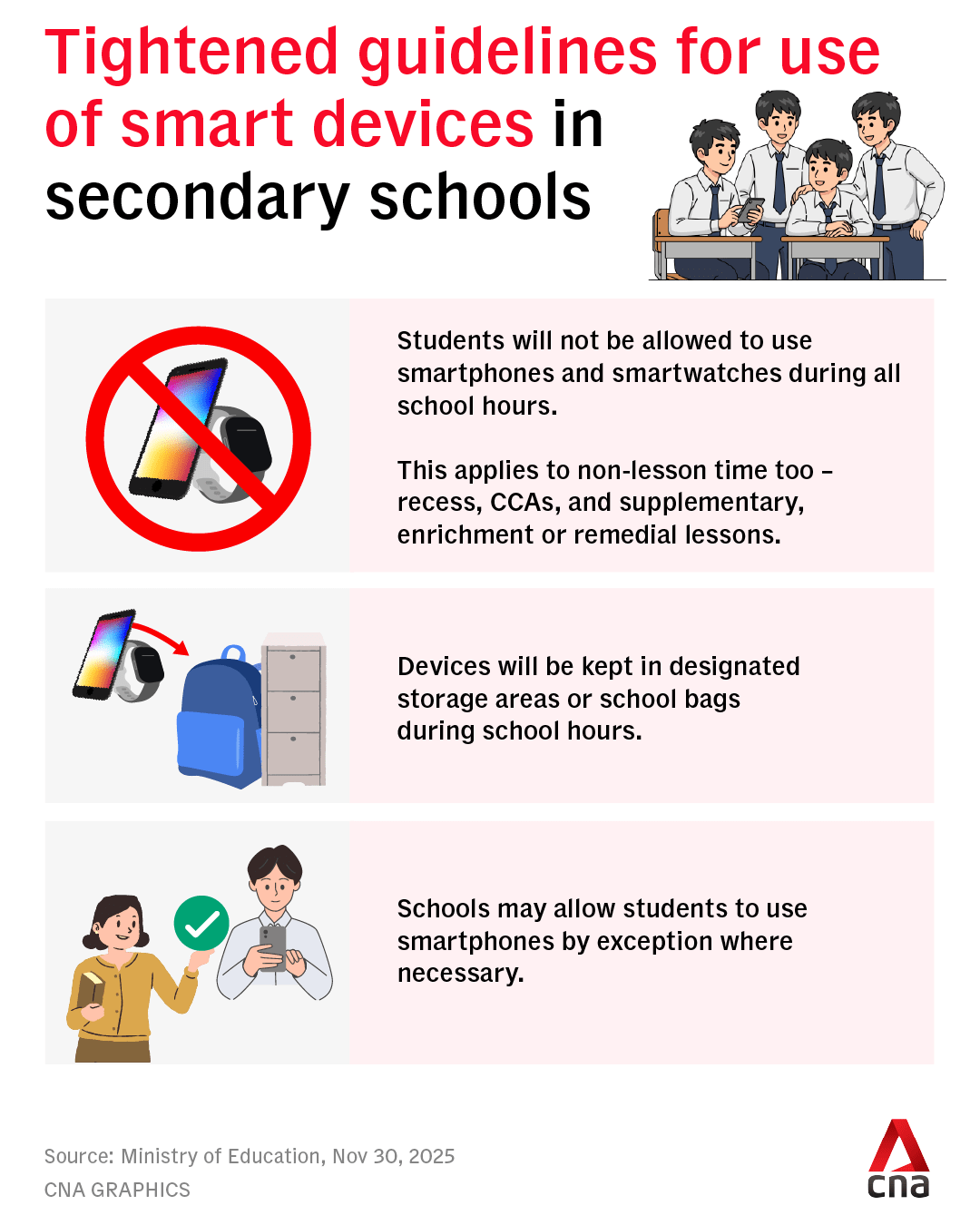

From Jan 2026, secondary school students will not be allowed to use such devices during school hours, including non-lesson time such as recess, co-curricular activities, as well as supplementary, enrichment or remedial lessons. Devices must be kept in designated storage areas or in students' school bags.

The same guidelines already apply to primary schools as they were rolled out at the start of 2025 to cultivate healthier screen use habits.

Parents and teachers CNA spoke to largely supported extending these rules to secondary schools, with some saying the move was long overdue. But many questioned whether schools would be able to enforce the guidelines consistently.

STUDENTS WILL FIND WAYS AROUND THE RULES

For instance, Mr Lam noted that the guidelines allow students to keep their phones in their bags, but he disagrees with this approach.

"Schools should have students put their phones in a locker, which is a better way to guarantee that they will not be able to use their phones during breaks," said Mr Lam.

Even then, he added, students "can find all sorts of ways to get around the rules".

Mr Kelvin Choo, who has five sons aged 11 to 19, shared similar concerns.

The 60-year-old has noticed that his sons have ready access to their phones during school hours – they often reply instantaneously when he sends them messages.

“The thing is, who’s going to be in charge to ensure that their phones are off or in the locker? It could be a dummy phone and they’re actually using another phone,” he added.

Ms Yvette Lim, whose 12-year-old daughter is entering Secondary 1 next year, said she has heard of parents giving their children dummy phones to surrender so they can keep using their real devices.

“In fact, I have also learnt of parents who encourage their kids, teach them how to work around the school rules in order to use their device,” said Ms Lim.

Several parents also noted that students can bypass restrictions through their personal learning devices, which may allow access to Web versions of WhatsApp, Telegram and other platforms. Personal learning devices are school-prescribed laptops or tablets to aid secondary school students in their learning — only apps approved by the school can be installed.

Ms Michelle Goh, who has one son in Secondary 1, said students sometimes still secretly access messaging apps or games in class through these devices, or even take unnecessary toilet breaks to use their phones.

“It will solve part of the problem, but not the whole problem. It’s a good enough solution for now,” said Ms Goh. “If they secretly change tabs, it’s also very hard to monitor.”

TEACHERS: WE CAN'T BE EVERYWHERE AT ONCE

Secondary school teacher Polly, who has taught for more than 10 years, noted “a sense of growing anxiety” among parents, who often ask for advice on managing their children's screen time amid their work schedules.

“They are worried about addiction, they are worried about obsessive compulsive behaviour regarding devices. They are also worried about what happens when the device is taken from the child … you get a lot of tantrums and anger management issues also arising when phones are confiscated,” she added.

There are also grey areas in the classroom setting. When students forget to bring their personal learning devices to school or fail to charge the devices, some teachers may allow them to use their phones to participate in the lesson, she said.

“While we generally discourage students from using their phones during lessons, in a matter of exigencies sometimes, we have no choice but to allow it,” said the teacher who declined to be named because she was not permitted to speak to the media.

She expects that the new rules are a signal from MOE that there will be stricter enforcement of the no-smartphones policy.

But there are challenges to this, she said. “Teachers can’t be everywhere all at once.”

Students may notice their peers breaking rules, but telling them to stop could invite mockery, she said.

Realistically, there will always be students who try to use their phones outside of the rules, said another former secondary school teacher who left the service this year. “I think it just depends on how much the school wants to enforce it."

There are a few things the school can do aside from installing lockers to store the devices, she said. Teachers and school prefects could be placed on patrol during break times, for example.

But keeping all the phones in one place may not be practical since students have different dismissal times. With schools already facing manpower constraints, sending teaching staff out on patrols may not be feasible, said the teacher, who also did not want to be named.

“Personally, I feel the kids need to understand the rationale. If you just go about policing … if the kids just feel like all the teachers are out to get them, then it will also defeat the purpose.”

Even though students are already not allowed to use their phones during lesson time, some still keep their devices under the table. “Of course, if they don’t take it out and use it, the teacher won’t say anything,” she added.

Nevertheless, some families do not think there will be major adjustments needed, since it is a continuation of the no-smartphone policy adopted by primary schools.

Ms Lim, whose daughter is entering Secondary 1 in 2026, said her child is already familiar with these measures because her primary school is “pretty strict” about the guidelines.

Communicating with her schooling daughter is not a problem. Ms Lim has left messages for her via the school office, or via text messages, knowing that she would read them after school.

“She’s perfectly fine with it because she’s so used to approaching the general office if she has to inform me of certain changes in her schedule for the day,” she added.

MEASURES HELP 'REBALANCE' SCREEN TIME

While some adjustments may be needed, there will be benefits if the measures are consistently and sustainably applied, said Professor Michael Chia, who studies screen time use at the National Institute of Education (NIE) at Nanyang Technological University.

“In any kind of enforcement, teachers should be sustainably supported and they can provide real ground feedback on how best to enforce these new measures. It is important to include students at all levels in this collective effort and garner support from them,” he added.

Further limiting the use of smartphones in schools will help to more consistently “rebalance screen time versus the rest of the time”, said Prof Chia.

“If left untampered, daily life across childhood, adolescence and adulthood, time on screens becomes disproportionately spent online,” he added.

Research on the harmful effects of excessive screen time — especially in childhood and adolescence — is “already quite compelling”.

Essentially, the new measures ensure protected time for children and teens to experience life beyond screens while they are still developing and discovering themselves without the echo chambers of social media that can distort reality, he added.

At the same time, students will be able to focus on in-person learning and social interaction without screens competing for attention.

Parents like Mr Jason Chew, whose two daughters spent a year studying in Australia, also recognise the struggle for students’ attention. He agreed that devices compete directly with real-world interaction — and saw a stark difference in his daughters’ behaviour when phones were more tightly restricted.

Mr Chew saw how South Australia's ban on mobile phones and other personal devices in all public schools from 2023 helped his daughters, who are now aged 12 and 13.

“Over there, my girls were quite used to not really using their phones that much because all the kids are on the same level playing field. They don’t really use it,” he shared.

Since returning to Singapore, however, his daughters often ask for 15 minutes of screen time to reply to friends’ messages immediately after he picks them up from school, instead of chatting with him about their day.

“From a parent’s point of view, that bond is also a bit affected. It becomes like a drug, they need it to fuel their satisfaction.”

With his daughters set to attend two different secondary schools from next year, Mr Chew's main concern is being able to contact them about pickup times. He already uses the built-in functions on their iPhones to limit their screen time – his daughters have to request approval to use their phones.

“Maybe it’s good to just give them a 10-minute digital break for them to just (contact us), and it could be supervised,” he added.