40 years after Sentosa cable car accident, survivor still struggles with trauma

The Sentosa cable car accident on Jan 29, 1983, killed seven people and left 13 others stranded above the water.

Mr Jagjit Singh was one of the survivors of the deadly Sentosa cable car accident on Jan 29, 1983. (Photos: CNA/Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

SINGAPORE: On Jan 29, 1983, Mr Jagjit Singh and six family members had just spent a fun-filled day in Sentosa. Dusk was setting, and they were about to return to Mount Faber on the mainland, where Mr Singh's godparents had parked their car.

At the time, the only ways to get to and from Sentosa were by ferry or cable car. The latter would take them straight to Mount Faber. Mr Singh, then an eight-year-old boy, waited with his family at the Carlton Hill station on Sentosa.

The first cable car that rolled in at about 6pm was red and numbered 26. Mr Singh still remembers vividly every detail from that fateful day – and he had a gnawing feeling getting into it.

"My favourite colour happens to be blue, and I just didn't feel comfortable with taking the red cable car that was coming first," he told CNA.

"So I told my godparents, 'Can we just take the blue one?' They said no, because we were rushing to go to a temple. I hope they had listened to me, because by the time the blue one came, I felt like the accident would have happened (before we could board)."

Mr Singh's cable car was one of 15 cars travelling between Sentosa and the mainland when the derrick of oil drilling vessel Eniwetok struck the ropeway at 6.06pm as it was being towed out to open sea.

The impact dislodged two cars, plunging them into the water 55m below. One of the cars was empty, but five passengers in the other car were killed.

Mr Singh's car swung so violently, making at least one somersault, that its doors gave way, flinging out three of its seven passengers. Mr Singh's godfather and grandmother died, but the third passenger – his cousin, who was just two years old – miraculously survived.

Mr Singh saw everything. The now 47-year-old has been diagnosed with anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

"It plays in my head every single day. There's not one day I can say that passes without me thinking about the incident, or it coming back as flashbacks," he said of the incident.

"I get flashbacks every single day. There are a lot of factors that trigger these emotions. Sometimes they are related to scenic places. If I happen to pass by the cable car tower, while going on the bridge to Sentosa, my head will always turn to the right.

"When I'm coming out I will turn to the left. It's automatically like second nature. You just turn to see the spot where the accident happened."

SELF-BLAME

Mr Singh still blames himself for what happened to his family, pointing out that they only brought him on a trip to Sentosa because he was having problems at school.

Growing up, Mr Singh was given away to his godparents, whom he said loved and pampered him a lot. And when he first went to primary school, he had trouble adjusting to a more regimented life, when teachers back then enforced discipline with what he called an "iron rod concept".

Mr Singh said he had a better time in Primary 2, noting that his teacher was "very nice". But this changed when he switched schools in Primary 3. Mr Singh recounted how he would recoil when an imposing teacher regularly went up on stage and yelled for students' attention.

"He was a very stoutly built, big-sized person and he would go up on stage and use the words 'sekolah sedia' (school, at attention). I would freak out because I couldn't get used to the loud shouting and all that," he said.

"So, I started to run away from school. It became like a routine every day – when the teacher shouts, I would leave the school and run. That became a problem for the teachers because they were accountable for my safety and everything."

In the next few weeks, Mr Singh's form teacher called up his godparents and suggested that they take him on an excursion, believing that the change in environment could help ease his problems.

"That was the first time I went to Sentosa and took the cable car. That was the first and the last time."

Mr Singh said he enjoyed his visit to the island. They started at 10am, joyriding the monorail and sightseeing at Fort Siloso. Their final stop was to get some ice cream. The shop only had enough left for Mr Singh's godfather. So his godfather gave it to him.

On the cable car ride back to the mainland, Mr Singh sat between his godparents, facing against the direction of travel. His grandmother and aunt sat across from them, separated by a central pole. In between the two women were his aunt's two children.

As the cable car headed towards the mainland and passed the first supporting tower, Mr Singh felt the first jolt.

The cable car then started to swing so violently that Mr Singh's grandmother stood and started to pray loudly, clinging to the centre pole. Mr Singh looked out and saw the cable car behind them swinging precariously. It was one of the cars that would eventually fall to the water below.

"I was basically in a state of shock. I had no idea what happened, what was going on and the severity of the incident," he said.

In less than 30 seconds, Mr Singh felt a second, stronger jolt. This time, Mr Singh's godfather stood and grabbed one of Mr Singh's cousins, who was two years old. The cable car oscillated wildly, somersaulting and flinging its doors open.

Mr Singh's godfather fell out of the car, but not before he threw Mr Singh's cousin to his grandmother. The grandmother held onto the child, but she too lost her footing. Both of them fell out.

"The impact was so bad that I sustained injuries in my head – I'm not sure to what extent. My godmother had a broken left arm, and her spine was badly injured also," Mr Singh said, his voice breaking.

Mr Singh remembers blacking out and only regaining consciousness hours later on the floor, noticing that the sky had fallen dark and the cable car was banged up.

"When they fell, for 25 years I would say I had no idea what happened to them and everything, because I was (above in the cable car)," he added.

"But when I did my own research and stuff like that, there's a lot of things I found out which I do not want to talk about."

What happened that day

The commission of inquiry investigating the accident found that of all the contributory causes of the accident, the failure of the towing mechanism on one of the tugboats was "particularly significant", in that it triggered the sequence of events that led to the accident.

"If the mechanism had not failed, the planned manoeuvre to take Eniwetok off berth, move her astern (backwards) and then turn her around, would probably have succeeded," the commission noted in its official report submitted to the President a day after the accident.

"However, even with the towline slipping, the accident could still have been avoided had there been the awareness of the risk of collision with the cableway."

Here's how the events of that fateful day unfolded:

12pm: The port operations centre receives a request to send a pilot to unberth the Eniwetok from the Keppel Harbour oil wharf at 5pm and take it to sea. The request note indicated the ship's name, tonnage, draught and length. A blank entry for the ship's height was not filled in.

4pm: Port of Singapore Authority pilot Adrian Cajetan Baptista was assigned to unberth the Eniwetok. He had a "good record" as a pilot, and had completed 1,140 ship movements with only nine minor reportable incidents.

4.15pm: Baptista arrives at the Eniwetok. There was a general understanding on board that the ship had to leave the wharf by 6pm, or departure would be delayed until the following day. Baptista informed the port operations centre by walkie-talkie that departure was expected to be delayed by half an hour because some documents still needed to be completed.

4.45pm: Baptista made his way to the bridge, or the ship's cockpit. Baptista introduced himself to the ship's captain, Pekka Erkki Joki, and explained his plan for taking the Eniwetok out.

Two tugboats, attached to towlines at the front and rear of the ship, would first pull it away from the berth before turning it 180 degrees anti-clockwise towards open sea.

There was no discussion on the height of the Eniwetok, or the relationship between this height and the height of the adjacent cableway.

There was also no discussion of a tide, which at the time was flowing towards the cableway at between 1 and 2 knots. Baptista stated that he only noticed the cableway as he was boarding the Eniwetok, and that once on board, it had not featured in his mind until the collision.

5.54pm: Baptista advised the port operations centre that the Eniwetok was still not ready to sail because some equipment was still being loaded.

5.55pm: Loading was completed. Baptista instructed the tugboats to stand by, and Joki agreed that unberthing could commence. The first manoeuvre was done, and the ship was now more or less parallel to the wharf. Baptista stated he was aware that the ship was now moving slowly ahead due to the tidal stream.

6.02pm: Joki noticed that the ship's rear was swinging in towards the wharf, causing its helipad to edge closer to a wharf crane. He told Baptista to tell the tugboat at the rear to pull, as the ship was swinging the wrong way. Baptista felt this happened because the tugboat at the rear had kept some tension on the towline to counteract the tide.

Baptista ordered the deckhand on the rear tugboat in Malay to "pull right". There was no response. The ship's rear swung more wildly towards the wharf. Baptista then shouted into his walkie-talkie to "pull hard". Joki rushed across and saw that the towline was in the water. At the same time, the deckhand on the rear tugboat reported: "Pilot, my line in the water."

The deckhand believed that the towline had slipped when he eased the tension on it at the end of the initial pull. He saw the safety catch come off and the towing hook fall and bounce on the supporting structure.

6.06pm: Eniwetok continued to drift towards the cableway due to the tide, with its rear swinging towards the wharf.

Baptista then asked Joki if the ship's propeller was clear, as he wanted to move backwards. Joki replied that it was not. Baptista said this was the main reason why he did not go backwards. Joki denied that this exchange took place.

Baptista stated that he then asked Joki to drop an anchor, and that Joki turned to a Caucasian man who gave a "thumbs down" sign. Joki denied this. His evidence was supported by two other people and accepted by the commission of inquiry.

Baptista decided to go ahead on the ship's main engine to avert a collision between its rear and the wharf, ordering "hard-to-starboard, dead slow ahead". This meant the ship would turn starboard, or to the right.

But this movement increased the swing of the ship's rear to the wharf, and Baptista realised his mistake. He then ordered "hard-to-port", or a movement to the left. An assistant dockmaster warned Baptista on his walkie-talkie: "Pilot your stern (rear) is falling on the wharf."

On the wharf, a worker noticed that the top of the ship's oil derrick appeared to be getting close to the cableway, and used his walkie-talkie to alert Baptista. Shortly afterwards, the assistant dockmaster shouted "pilot go astern (backwards), pilot go astern" over the walkie-talkie.

Joki said that Baptista then ordered an anchor be dropped. Joki, concerned that things were going awry, put the engine to "full astern" and shouted over a PA system to "drop any anchor".

Close to 6.07pm: From the wharf came shouts of "cable car, cable car". Baptista ran out and looked up, seeing the top of the derrick hitting the cableway wires. Shortly afterwards, two cable cars plunged into the sea.

Joki then rushed out and saw "cars dropping, falling down" and a "big splash in the water". He also heard people screaming.

Findings

The commission of inquiry found Eniwetok's captain Joki and Port of Singapore Authority pilot Baptista to be "grossly negligent" and their conduct to be the "dominant cause" of the accident.

The commission highlighted that breaches of statutory duties and the negligence of other parties, including the Port of Singapore Authority, Keppel Shipyard Limited and Eniwetok's chief officer Robert Thomas Mahon, contributed to the accident.

RISKY HELICOPTER RESCUE

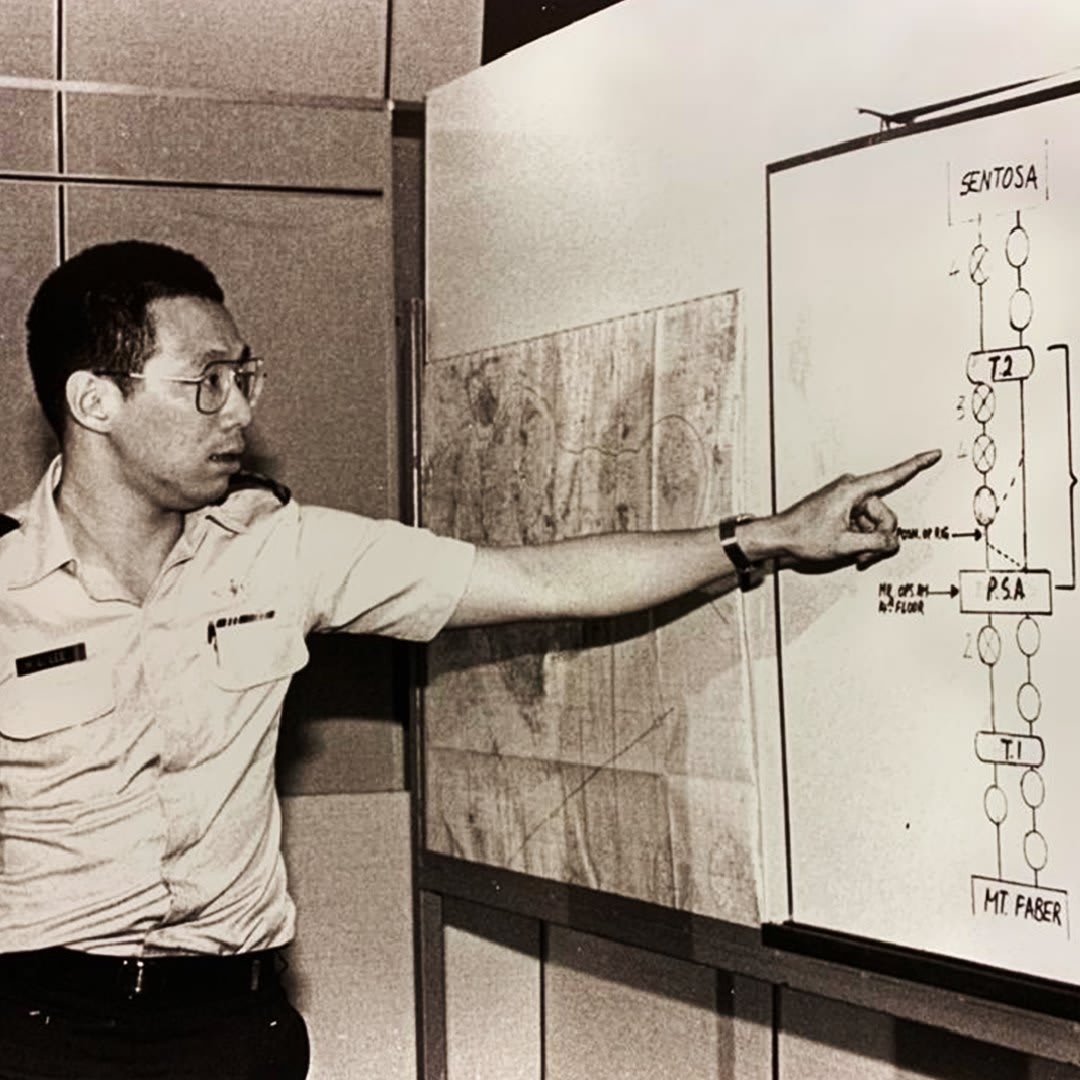

Behind the scenes, a rescue planning team headed by then-Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) Colonel Lee Hsien Loong – now Singapore's Prime Minister – came up with three options.

The first was to use tall equipment to reach the stranded passengers – a fire brigade snorkel ladder for the cars over land and a floating crane for those over water. This option was dropped because the ladder and the crane were not tall enough.

The second option was for SAF commandos to crawl along the cables and secure the cars that were in danger of falling. They would also climb into the cars, attach pulleys to the cables, and lower stranded passengers down to safety.

This option was thought to be feasible but difficult to execute. It was eventually decided that this would be the back-up plan if the third option failed, a Singapore infopedia article about the incident said.

This third option was for military helicopters to lower winchmen to the cable cars. These winchmen would then haul up stranded passengers into the helicopter.

Despite concerns about night flying conditions as well as the potential for downdraft from the helicopters’ rotor blades to further rock the cable cars, this option was given the green light.

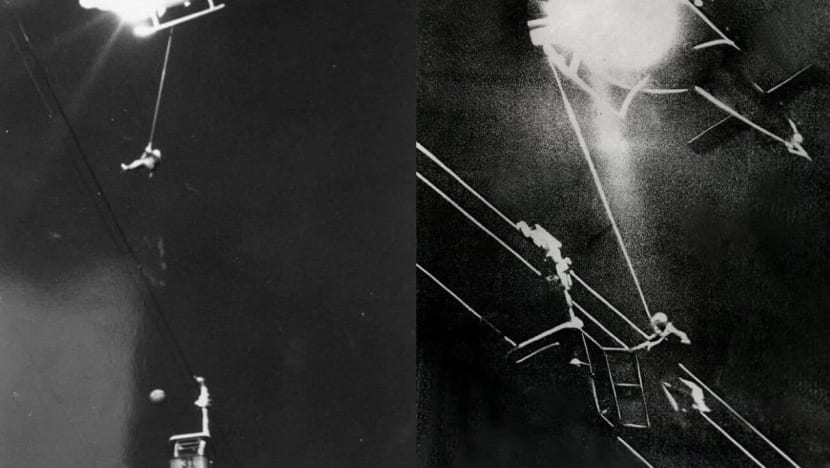

Following a successful practice run using an empty cable car, rescue operations started at 12.45am using two Bell 212 helicopters, each with a crew of four.

One helicopter rescued six people from the two cars over land. The other helicopter rescued seven people trapped in the two cars over water.

The helicopter that rescued the passengers – including Mr Singh – over water was flown by Australian naval officer Geoff Ledger, who was coincidentally in Singapore to help build up the Republic of Singapore Air Force's (RSAF) search and rescue capabilities.

"He did not have to fly this mission, but he did, piloting one of the helicopters. It was a risky operation, at night under windy conditions, but fortunately the rescue succeeded," Mr Lee said in an address to Australia's parliament during an official visit in 2016.

CNA was unable to reach Mr Ledger for comment, including through his social media account. But he told TODAY in 2016 that he chose to take part in the rescue operation as he was proud to be serving his country in Singapore.

“It was a torturous time. The only area I had as a hover reference was one of the wires, and I was listening to my winch operator telling me how close I was getting to the cables,” he said.

A Royal Australian Navy Facebook post in 2016 detailed how Mr Ledger flew in up to 15-knot winds, as the downwash from his rotor blades buffeted the cable car and his winchman, RSAF's Selvanathan Selvarajoo.

"The winchmen were swinging around in darkness about 60 metres above the water trying to find the door handle to get into the cable cars," the post said, quoting Mr Ledger.

"They did not know what to expect once they opened the doors. Some of the passengers could have been hysterical. They knew some were injured and had two children to look after.

"In fact, one eight-year-old boy did become hysterical and refused to leave the cable car. He changed his mind after being smacked by his aunt."

GETTING SLAPPED

That boy was Mr Singh.

After coming to, he realised that everyone left inside the cable car were calm and completely silent. His godmother sat with him on the floor in one corner. She had used her scarf to tie themselves together.

Mr Singh was hopeful that his three family members had survived the fall.

"All I could see from that angle sitting on the floor was just shining lights from below. There were a lot of thoughts going through my head," he said, his voice trailing off.

Mr Singh said he kept telling himself that someone would have seen the accident and called the police, adding that he waited until about 3am for the rescue.

At that time, he saw a helicopter hover beside the cable car. Someone forced the doors open and shone a light inside. Mr Singh thought this was the moment he was waiting for, but the chopper flew away.

Mr Singh did not realise that above, the second helicopter piloted by Mr Ledger was preparing to lower Mr Selvarajoo. Because of the gusts, Mr Singh recounted Mr Selvarajoo swinging from side to side as he inched towards the car.

Mr Singh said Mr Selvarajoo tried to hold the doors open, but they kept flinging in the wind until they smashed into his left thumb. He heard Mr Selvarajoo saying "ouch", then saw the winchman eventually use a hammer to jam the doors open.

Mr Selvarajoo took Mr Singh's other cousin first because he was the youngest. When Mr Selvarajoo came back for Mr Singh and tried to put him in a harness, he refused.

"It's not because I was scared or whatsoever. It's because I already lost my godfather and grandmother, and I didn't want to lose my godma," Mr Singh said, highlighting that he was not afraid of dying then.

"So, I wanted her to go up first or we go together. My aunty ... she basically slapped me in that state I was in. After that I was just numb, and the guy slowly pushed me to the door and brought me up to the helicopter."

As Mr Singh was winched up, he stared below at the cable car's roof. This scene became etched in his mind and soon returned to him in regular flashbacks – seeing himself being pulled up from that battered red car.

The entire rescue operation finished at about 3.45am. All 13 people rescued from the two cable cars were airlifted to Singapore General Hospital.

SINKING IN

For Mr Singh, the flight to the hospital was quiet too. Besides his cousin and aunt, Mr Singh remembers who else were on board: Two pilots, the winchman and a bespectacled doctor in a white T-shirt.

The helicopter landed on a helipad at the hospital, and Mr Singh was put in a wheelchair. He was rushed to a holding area, where the media took flash photographs and desperate family members waited.

Mr Singh remembers a policeman offering him a chocolate biscuit and Milo beverage to dip the biscuit in. He glumly turned them down.

"I didn't eat anything because the helicopter didn't come back with my godmother. Only when I saw my godmother then I felt at ease."

When Mr Singh woke up in the children's ward later that day, he found out that his two-year-old cousin had survived the fall into the water and was in the intensive care unit. But when he asked about his godfather, answers from family members were less forthcoming.

They initially told him that his godfather was in another ward, hesitant to tell him the devastating news. Mr Singh said it slowly sunk in.

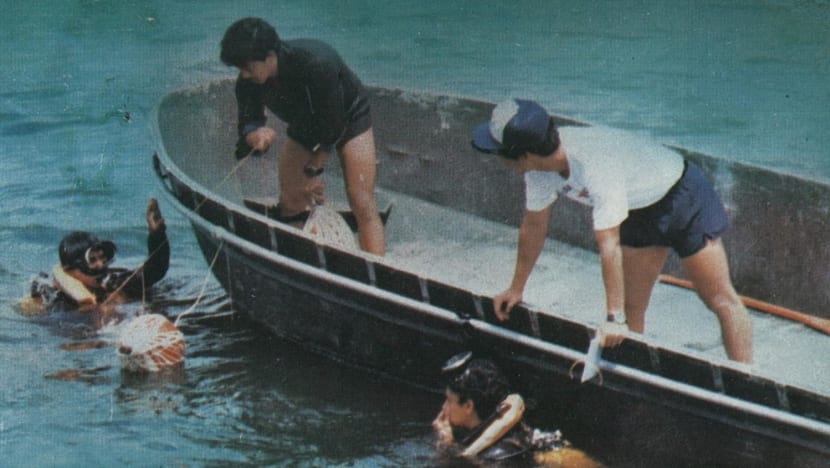

Shortly after the two cable cars plunged into the water, port workers had jumped into their boats and tried to rescue those who were underwater.

They pulled out Mr Singh's cousin, who was unconscious. They also retrieved three bodies, including Mr Singh's grandmother and godfather. Naval divers subsequently recovered another four bodies from a sunken cable car.

A local media report described how Mr Singh's godmother, injured and sedated, was permitted to see her husband for the final time before he was cremated, in line with Sikh custom. She left crying in an ambulance.

HEALING PROCESS

Mr Singh had trouble coming to terms with the incident amid feelings of loss and self-blame, some which still linger today. He told CNA that he has over the years tried different types of medication and therapy, but nothing seemed to work.

"I think I've left no stone unturned, every single avenue that you can help from. You can't get help for this," he said.

Mr Singh said the first two years following the incident were particularly "devastating" for his godmother, but she persevered with a "strong will", putting on a brave front and caring for him until she died in 1996.

"I just know that my godmother never blamed me for it, and I love my godmum until now even though she's not alive anymore," he said, his voice tinged with emotion.

"Basically, I was her hope and she was my hope to live. Without my godmother I wouldn't have survived."

Nevertheless, Mr Singh's religious faith and a newfound passion pushed him through. A teacher introduced him to the events industry, and for the past 20 years he ran his own events company, doubling up as an emcee, disc jockey and comedian.

Mr Singh also organises an open mic stand-up comedy show where he gives performers who have been turned down elsewhere their chance in the spotlight.

"Now, the only thing that motivates me to live on, to be very honest with you, is my passion for what I do, which is the open mic," he said.

"When I see other Singaporeans coming in who are not given a chance anywhere else ... it gives me more pleasure in helping people succeed."

FINDING CLOSURE

The day after the collision, then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew ordered an official inquiry into the causes of the accident.

A commission found that the accident was due to an unfortunate combination of factors that would not have caused the tragedy if they had not coincided that day.

Investigations revealed that the accident occurred because the Eniwetok, which was being towed out to sea, had broken loose from its tugboats.

The commission identified the failure of the towing mechanism as the trigger but named a few parties as being responsible for the accident, due to gross negligence.

They included the ship’s captain and chief officer, as well as the Port of Singapore Authority-appointed pilot.

Subsequently, ships taller than 52m were barred from entering Keppel Harbour, while laser height sensors and stringent entry procedures for ships between 48m and 52m in height were implemented.

The cable car system, judged to be sound and operable, was absolved of blame. It resumed operations in August 1983, after months of tests and repairs.

Mr Singh said the official findings have not given him closure. Instead, he copes by trying to learn more about the incident, through keeping extensive records like video footage and newspaper clippings, and chatting with those involved.

Mr Singh yearns to revisit the scenes of his rescue, like that point in mid-air where he was winched up to the helicopter, or at the hospital helipad where his legs finally touched the ground. He has tried to charter a helicopter to take him to these spots, but to no avail.

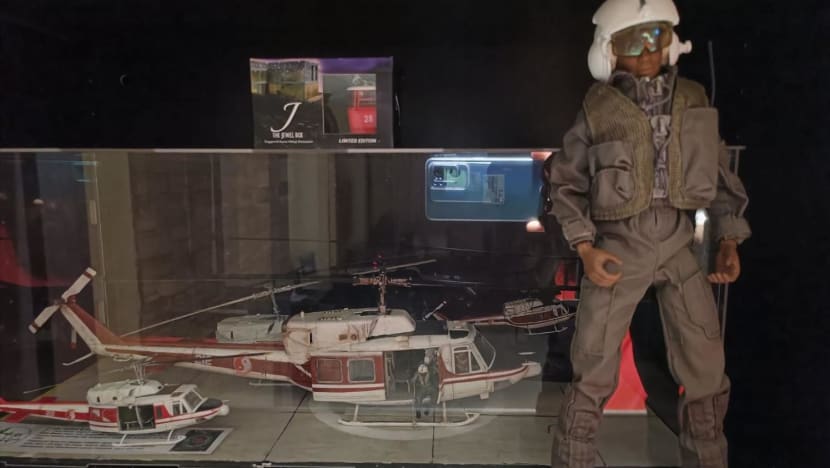

For now, Mr Singh keeps in a plastic case various-sized models of the same Bell 212 helicopter that saved him, complete with its crew members and equipment.

"When I see these things, it reminds me where I came from, and it makes me become more grateful for what I have now," he added.

"And that's the way that, unknowingly, might be healing me."