Singapore tables law outlining how workers can file workplace discrimination claims

Workplace discrimination claims can be sensitive and socially divisive, and preserving harmony is a priority in dispute resolution, said the Manpower Ministry.

More employees have returned to the office in the post-pandemic era. (File photo: iStock)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: A draft law outlining how workers can file discrimination claims under the new Workplace Fairness Act was tabled by Minister of State for Manpower Dinesh Vasu Dash in parliament on Tuesday (Oct 14).

The Bill follows a previous one on the landmark anti-discrimination law, which was about what the law will cover and what employers are expected to comply with.

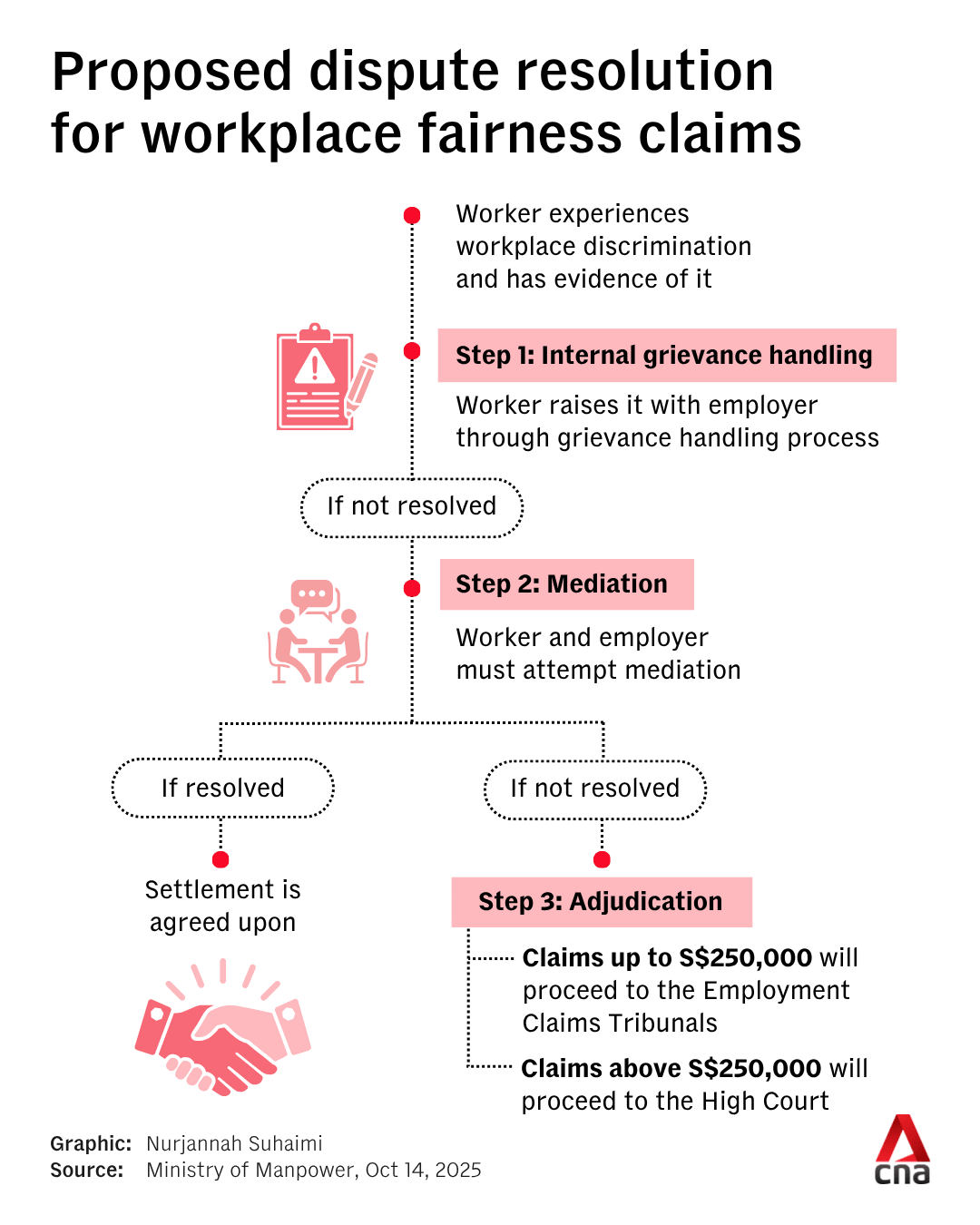

The latest Bill focuses on the dispute resolution process by proposing a dispute resolution framework that aims to help parties find “amicable, quick and just” resolution, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) said at a briefing on the draft law.

“Workplace discrimination claims can be sensitive and socially divisive. The tripartite partners agree that preserving workplace harmony must remain a priority when designing the dispute resolution process,” MOM said.

In January, lawmakers unanimously supported the first Bill that enacted the Workplace Fairness Act and established age, nationality, sex, race and disability as areas where workers are protected against discrimination.

Employers who break the law can be ordered to attend educational workshops and pay financial penalties.

Parliament is expected to debate the second Bill in November. If it is passed into law, the Workplace Fairness Act is expected to come into effect in 2027.

MEDIATION AND TIME BARS

MOM said the proposed dispute resolution process encourages parties to resolve disputes amicably among themselves.

Under the draft law, the first step for a worker who has experienced workplace discrimination is to raise this with the employer.

The matter is expected to go through the company’s grievance handling process, which the Workplace Fairness Act requires companies to have.

If the matter is not resolved internally, both parties should try mediation as a second step before seeking adjudication as a last resort, said MOM.

Jobseekers who have encountered discrimination during recruitment are not required to go through the company’s internal grievance process before attempting mediation. They can approach the Tripartite Alliance for Fair and Progressive Employment Practices (TAFEP) for assistance instead.

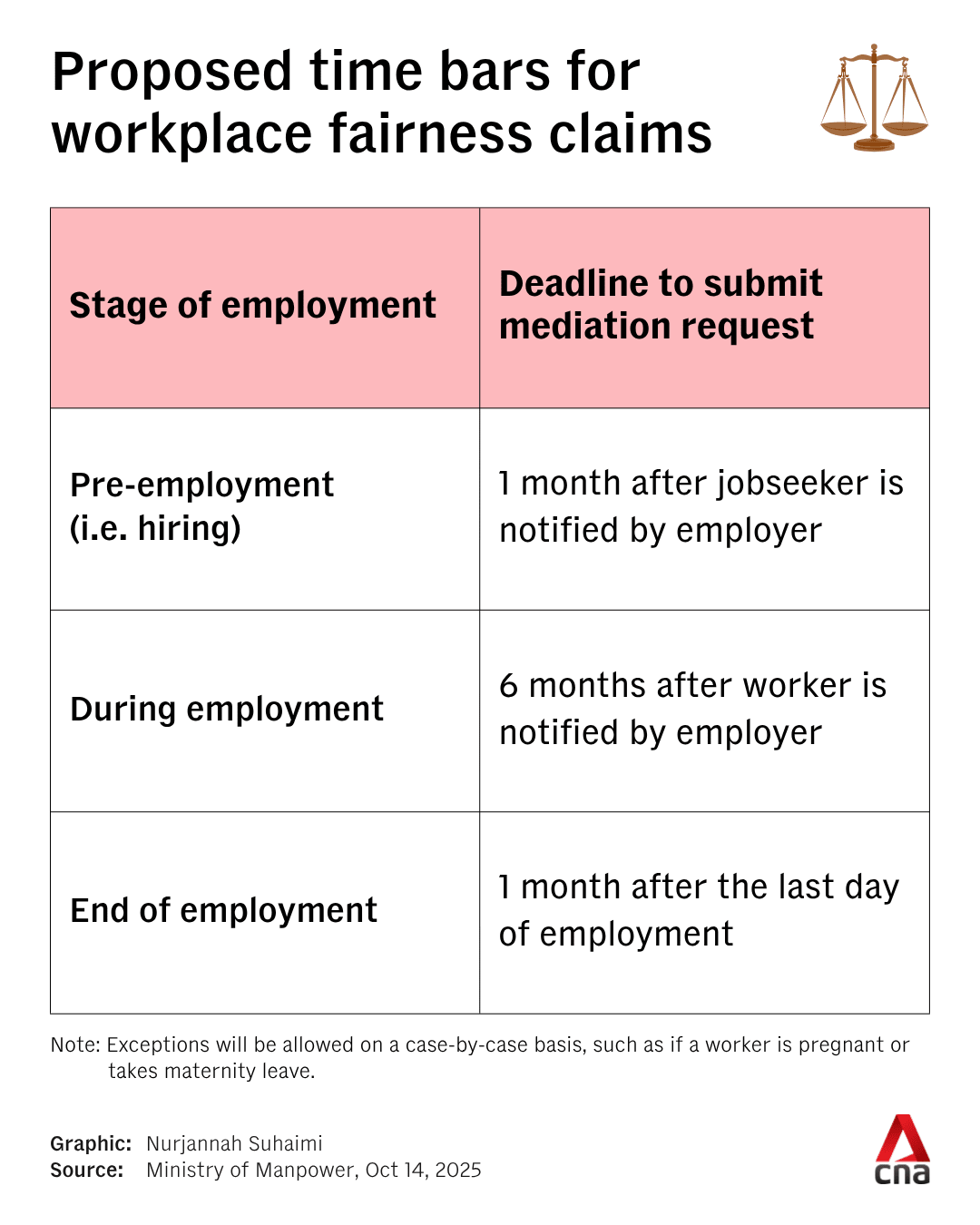

Workers must follow “time bars”, which are stipulated time limits within which they must make the workplace fairness claim.

“The time bars will encourage individuals to come forward in a timely manner, before evidence degrades, while providing employers with some certainty that incidents will not be dredged up,” said MOM.

Time bars are counted from the employer’s date of notice to the worker about the disputed decision. They differ depending on the stage of employment.

In the pre-employment or hiring phase, the deadline is one month from the employer’s date of notice.

When a worker is in employment, the deadline is six months from the employer’s date of notice.

For these stages, exceptions will be allowed on a case-by-case basis, such as if the claimant is pregnant or takes maternity leave. If no notice was given, the time bar will be counted from the date of “deemed notice”, said MOM.

When employment has ended, the deadline is one month after the worker’s last day of employment.

Asked about the expected timeline for resolving workplace fairness disputes, the ministry said it was difficult to say for now.

The Tripartite Alliance for Dispute Management has an eight-week estimate for existing types of employment disputes, which include salary-related and wrongful dismissal claims.

But these types of claims are generally simpler than what is expected to come from allegations of workplace discrimination, said MOM.

ADJUDICATION AND CLAIM AMOUNTS

If a case moves to adjudication, the Employment Claims Tribunals (ECT) will hear workplace fairness claims involving amounts up to S$250,000 (US$192,000).

The S$250,000 threshold is pegged to the limit for civil claims heard at the District Courts, MOM said.

Workplace fairness claims above this threshold will be heard at the High Court, like other civil claims.

The ECT’s existing claims threshold for salary-related and wrongful dismissal claims is lower, set at S$30,000 for cases with union-assisted mediation.

MOM said the higher threshold for workplace fairness claims does not imply that they are expected to reach significantly higher amounts than other employment claims.

Rather, the intent is to ensure that the “vast majority” of Workplace Fairness Act claims are heard by the ECT.

“Given the sensitive nature of discrimination claims and the importance of preserving workplace harmony, most (Workplace Fairness Act) claims should be heard in the less adversarial ECT setting, with simplified procedures that workers can navigate without the need for legal representation,” said MOM.

Few claims are expected to reach the upper limit of the ECT, and claimants will need to quantify and justify the compensation they seek, the ministry added.

For claims involving discrimination at the pre-employment stage, there will be a S$5,000 limit on compensation.

This was a recommendation made by the Tripartite Committee on Workplace Fairness, considering that there is no employment relationship between the jobseeker and the company.

The tripartite partners will explore how to educate workers and employers on the appropriate compensation amounts for different contexts, to prevent claim inflation.

What happens at the Employment Claims Tribunals

The ECT was established in 2017. According to MOM, it offers a dispute resolution process that is quick, just and easy to understand.

Currently, the ECT hears salary-related and wrongful dismissal disputes. The maximum claim amount for such cases is set at S$20,000, or S$30,000 if the case has gone through tripartite or other union-assisted mediation.

The Workplace Fairness Act will involve expanding the ECT’s monetary jurisdiction only for workplace fairness claims, to S$250,000.

The claim limits for salary-related and wrongful dismissal cases will not change. MOM said that these limits have operated well to cover most claims and involve clear calculations, such as of the amount of salary or notice pay owed.

“Overall, the different claim limits reflect the distinct nature of these dispute types,” said the ministry.

Currently, legal representation is not allowed at the ECT. This is also intended to be the case for workplace fairness claims.

Time bars currently exist for salary-related and wrongful dismissal claims, and are also being proposed for workplace fairness claims.

For salary-related claims, the deadline for filing a claim is within one year from the dispute if employed, or within six months from the last day of work if no longer employed.

For wrongful dismissal claims, the deadline for filing a claim is within two months from the date of confinement for pregnant employees, and within one month from the last day of work for other claimants.

FEATURES OF WORKPLACE FAIRNESS HEARINGS

Workplace fairness claims at both the ECT and High Court will be heard in private. Hearings will be closed to the media and other members of the public.

MOM said private hearings will preserve workplace and social harmony by minimising the inflammation of social tensions and public resentment against parties, especially when a case is ongoing.

Private hearings will also allow parties to share their honest views and focus on the ongoing case, without third parties present who may misrepresent or sensationalise the dispute, said the ministry.

However, this does not mean that gag orders will be imposed or that judgments will not be published. If the state takes enforcement action against errant employers, these will also continue to be public.

Both the ECT and High Court will adopt a “judge-led” approach, where the judge takes a proactive role in managing the case, said MOM.

This will include “guiding parties to define or narrow the key issues, filtering out irrelevant matters, and focusing on the evidence required”.

Judges can also take steps to move the case forward efficiently by making procedural orders on their own initiative, without formal applications from the parties.

This helps parties without legal training to navigate the claims process smoothly, said MOM.

Legal representation is not allowed at the ECT for all types of claims. Workers and employers can seek support from their respective unions, such as advice on their rights and obligations.

Asked about the rationale for this, MOM said that having no legal representation helps to ensure a “level playing field” between workers and employers.

The “judge-led” process also facilitates the ECT’s “quick and just” approach that does not involve any party incurring legal costs, said MOM.

This has worked well so far, and the experience has been that legal representation is not required for the types of disputes the ECT currently handles, the ministry said.

Even though legal representation before the ECT is not allowed, parties can seek legal advice outside of the ECT if there is a need to do so, added MOM. They can also seek union representation.

Workers’ union representatives can represent worker members in unionised companies in mediation and ECT hearings, for workplace fairness claims up to S$250,000.

Employers’ union representatives can represent employer members in mediation and ECT hearings for claims between S$30,000 and S$250,000, and only when the worker filing the claim can be represented by a union.

Union members in non-unionised companies can tap on tripartite mediation advisors, who are typically experienced industrial relations practitioners, said MOM.

Legal representation is allowed for workplace fairness claims at the High Court.

MOM said there are also safeguards against frivolous claims at both the ECT and High Court.

Judges can strike out claims at their own initiative, and companies can also apply to strike out claims.

Workers who pursue claims that are frivolous or vexatious can be ordered to pay costs, face restrictions on further proceedings or be investigated for abusing court processes.

To prepare for implementation of the Workplace Fairness Act, MOM encouraged employers to take stock of their human resource practices in line with existing Tripartite Guidelines on Fair Employment Practices.

There will be a new handbook to help workers and employers understand and apply the law, while TAFEP will also continue outreach and education efforts, the ministry said.

LABOUR MOVEMENT WELCOMES MOVE

In a statement, National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) Assistant Secretary-General Patrick Tay welcomed the proposed law, calling it a "fair, accessible and expeditious claims process for workers".

He said the S$250,000 threshold for workplace fairness claims at the ECT opened the door for more workers – including professionals, managers and executives – to access an affordable and expeditious claims process that does not require legal representation.

"This ensures that workers' grievances on discrimination can be resolved affordably, quickly, and in private, while safeguarding workplace harmony," he said.

NTUC will equip union leaders and industrial relations officers to guide and support members through workplace fairness claims when the law comes into force, Mr Tay added.

The labour movement will also continue working upstream with companies to strengthen human resource practices to address discriminatory practices on the ground, and will gather feedback from workers to share with tripartite partners.