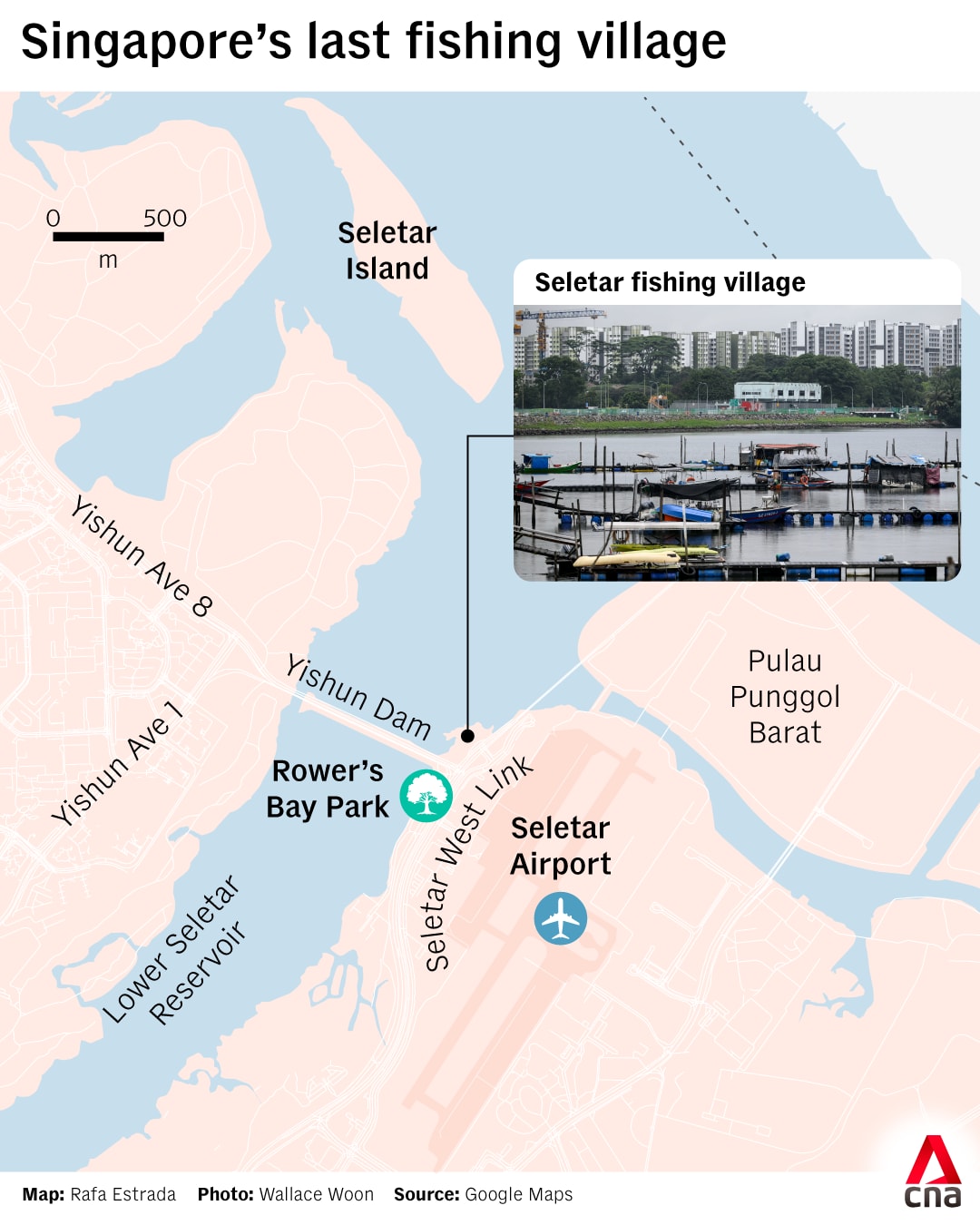

IN FOCUS: In Singapore’s last fishing village, tradition resists urbanisation – for now

Members of a quiet coastal community in the country’s northeast say they have been “waiting indefinitely” to be pushed out.

A man walks out along the jetty at the Seletar fishing village on Sep 1, 2025. (Photo: CNA/Wallace Woon)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Carrying a bucket of freshly caught prawns, Toh Eng Loo makes his way down a long jetty, boots thumping against the wooden planks with every step.

Stepping into a zinc-roofed shed to get some respite from the afternoon sun, he meets one of his regulars, who promptly asks in Teochew dialect: “Ah Loo, tomorrow I want 10kg, can or not?”

The 62-year-old fisherman is the son of a caretaker – one of three looking after four piers lined with boats, jutting out and over the water from a quiet, fenced sanctuary in Singapore’s northeast.

In this space of around four basketball courts, there is no fresh water supply; the 30 or so occupants collect rainwater to use. Electricity comes from generators and solar panels. Toilets are charming cubicles with holes, to do one’s business directly into tides ebbing in and out of the Johor Strait.

This is Singapore’s last kampung-style fishing village of its kind. And the survival of the place, its people and their peculiar way of life is not guaranteed.

The rustic enclave nestles in mangrove trees in a corner of the Seletar area, with public housing blocks looming in the distance and vehicles whizzing along the adjacent Yishun Dam.

That busy stretch serves Yishun and Sembawang residents looking to connect to major expressways, and it has symbolised the urban sprawl threatening to encroach on the fishing village for years now.

Since 2003, successive development masterplans have marked out the site as a landing point for a bridge parallel to the dam. And in 2019, the village community started making preparations to exit, Mr Toh told CNA in Mandarin.

“The authorities had already begun coming down and taking measurements and making arrangements,” he said. “But after COVID-19, the plans changed.”

“Since then we haven’t heard any updates. So we are now just waiting indefinitely.”

RESETTLED AND SETTLED

The Seletar village comprises people who once stayed in kampung-style fishing settlements scattered around northeastern Singapore.

When Yishun Dam was built in 1983, it created what is now known as Lower Seletar Reservoir, and forced some of those communities to move. Others came from Punggol, where kampungs and jetties made way for Housing Board flats; or along the Sembawang shoreline.

The village used to be located a little closer to the sea, before moving to its current location about 15 years ago.

That shift was prompted by, again, a bridge: The Seletar North Link connecting the mainland to Pulau Punggol Barat was constructed over where the village once sat.

Urban studies researcher Diganta Das from the Nanyang Technological University (NTU) traced the gradual resettlement of fishing communities to the start of Singapore’s urban development and economic pragmatism.

The Seletar fishing village is in fact a place of business, with no one actually living there. Mr Toh and other fishermen – all mostly in their late 50s to 60s – sometimes sell their seasonal catches at markets or the lone fishery port in Singapore.

The bulk of their customers, however, are long-time friends, relatives and regulars who for decades have been heading down to the village to directly purchase fresh fish, prawn, crabs and the like.

Prawns go for about S$25 (US$19) per kg here. In markets around Singapore, it could be around S$38 for a similar amount, due to additional overheads like transport, fishermen told CNA.

Painting contractor Peter Ong swings by every week or two to buy seafood from his fisherman friend, who he’s known since kampung days before the 1980s.

“The prawns they catch here are so fresh as they are usually caught on that morning itself,” said the 62-year-old, as he showed off a 20kg haul in two styrofoam boxes. “If I want to eat good prawns, I don’t go to the market, I just come here.”

Also operating out of the village are private boaters who fish not for commercial reasons but leisure and their own consumption.

Mr Herman Onn, a lift engineer who owns a vessel docked there, spends at least eight hours fishing every weekend, sometimes pulling all-nighters. For the 60-year-old, sharing his catch with friends is an act of harking back to the sense of community of his kampung days.

“Maybe I give you some fish, then you give me maybe S$10 to cover my petrol or other costs, that’s all … One person want to eat so many fish for what?” he laughed, adding that neither family nor friends take it for granted that they will regularly get fish from him.

Then there’s retiree Tan Hua Keng, who has parked his boat at the Seletar fishing village for 14 years. He drives there in his lorry every other day to water his plants.

“I have nothing to do anyway. This place is quite cooling actually, and there’s free parking,” said the 71-year-old former odd job worker. “We come here to relax and gather with our friends and chit chat.”

The Maritime & Port Authority (MPA), which licenses jetty operations at the village, told CNA the ports there “were designated to accommodate craft owners relocated from various Singapore’s offshore islands”.

Arrangements are “subject to periodic review” and “there are no plans to expand berthing capacity there”, said a spokesperson.

Besides the fishermen and boat owners, there are former kampung buddies just looking to hang out and pass time at the village. Mostly everyone is a pensioner. “No youths come here,” said Mr Toh, the caretaker’s son.

DUTY TO COMMUNITY

The other custodians of the village include 55-year-old Kelanasari Eeban, who started overseeing one of three compounds after his uncle died a few years ago.

Members of the community told CNA the third and last caretaker was a Chinese man in his 80s, hard of hearing and without any children.

Mr Toh’s 88-year-old father Toh Teck Yee is in ill health but still a registered caretaker, even if it’s his son looking after their assigned area.

That involves ensuring the upkeep and maintenance of both the land and the jetty. For the latter, professional engineers are hired – on the caretakers’ own dime of about S$800 – to annually certify the safety of the structures.

The Singapore Land Authority (SLA) also charges a fee for a Temporary Occupation License (TOL) for use of the village space, such as storing fishing equipment.

“Each year, it was S$800 plus GST (goods and services tax), in the early 1980s,” said Mr Toh. “Nowadays, it’s easily over $2,000.”

CNA understands the TOL fee is assessed by the authority, and based on factors like land area, location, usage and market rates.

Boatmen and fishermen at the village pay up to S$60 monthly to the caretakers, who lamented the “loss-making endeavour” of running the place.

“My dad has been making a loss for many decades already,” said Mr Toh, who took over his father’s boat in the 1990s when the senior Mr Toh retired.

“Nowadays, every year you collect about S$10,000 in revenue from docking fees from the boat owners. It barely covers everything … Yet, we remain here doing this as it is our duty to society.”

He shared that when a fishing community in Changi were being resettled years ago, the authorities suggested shifting some of the boats up to the Seletar village, to be placed under the charge of his father.

“But my father did not take up that offer, as all along he oversaw this place just as a duty to his community. It was never to make any profit,” said Mr Toh.

In any case, fishing is becoming less viable as a career, against the rising cost of living, he noted.

“A lot of fishermen … go out and drive Grab or drive taxis to earn a living, after putting out their nets each day,” he said. “Just a minority of us are full-time fishermen. It’s simply not sustainable to make a living.”

A PRIVATE THIRD PLACE

Passers-by and explorers encountering the Seletar fishing village will find that the community’s privacy is jealously guarded.

To get to the jetties, one has to pass fenced premises manned by security, before meeting a gate for each compound with signs warning against unauthorised intrusion.

The Singapore Police Force told CNA that fences were installed on the perimeter in September 2019, both to deter unlawful entry into and exit from Singapore via the sea, as well as prevent criminal activities such as the smuggling of illicit or prohibited items.

“Everybody who comes in and goes out must be registered; either owning a boat there or whom we’ve been informed beforehand of their arrival,” said a security guard who asked to stay anonymous. “There are some members of the public who will cycle over and try to come in and see the place, but I have to follow the rules and turn them away.”

Unfamiliar faces would instantly register in the small community of regulars.

“It’s basically a private place ... Just like a private property, you don't just let anybody come into your house right?” said a 55-year-old boater, who didn’t want to be named. He said there were instances in the past where people entered and stole things from the boats.

Safety is another issue: Should a visitor fall or get hurt on the jetties, members of the community are not keen on being blamed or worse, made liable.

Still, they can do little about the increasing attention being drawn to their abode, in part due to the development of the surrounding area – namely, new roads around Yishun Dam in 2015 and Seletar Aerospace Park being built up.

The 55-year-old boatman also said the surrounding mangroves were slowly dying, and that more coastal trash has been drifting in.

Mr Lee Jek Suen, 50, business development lead at social enterprise Green Nudge, said his organisation holds regular beach clean-ups at Yishun Dam, among other places.

His group’s efforts have helped the occupants of the village, which he said he has never attempted to visit because he doesn’t want to intrude.

“It seems like a pretty laidback place,” said Mr Lee. “It kind of feels like a part of Singapore that is going to disappear.”

A CHANCE OF PRESERVATION?

Under the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s (URA) latest draft masterplan released in June, a new bridge over the Seletar fishing village – and parallel to Yishun Dam – remains part of considerations.

In response to CNA’s queries, URA said the rationale was to “support any potential increase in vehicular traffic from future development”.

“Agencies regularly review our plans, and more details will be shared in future, should it be assessed that development of the road is required,” a spokesperson added.

Member of Parliament and heritage advocate Cai Yinzhou said that from the government's planning perspective, land development is largely to prioritise the needs of the population. He also sits on a government parliamentary committee for national development.

“Traffic on the Yishun Dam carriageway can get quite crowded,” said Mr Cai, noting a need for road expansion in the area.

Residential and commercial developments in the surroundings are probably on the agenda as well, said other observers.

But some believe that even if the bridge and other developments are built, the fishing community could remain where it is.

“The dam's location adjacent to Lower Seletar Reservoir and its close proximity to Seletar Airport makes extensive redevelopment of the area unlikely,” said urban policy and governance researcher Woo Jun Jie from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

While there may be some short-term impact on the fishermen's activities due to construction work, the site is likely to remain preserved as a green space, he said.

Mr Stanley Cheah and Ms Amanda Cheong, founders of the Hidden Heritage Collective consultancy, said any development at the village – which they referred to as “definitely the last of its kind at this scale” – could be subject to height limitations due to the proximity to Seletar Airport.

They also pointed to the nearby Seletar Aerospace Park as a possible example to follow, where many colonial buildings have been conserved while at the same time repurposed for new functions.

Similar calls have been made to retain the Seletar fishing village for educational or recreational purposes, such as by blending it with the upcoming Khatib Bongsu nature park.

Mr Ng Wee Liang, a National University of Singapore undergraduate who posts heritage content on social media, noted that the village doesn’t take up much land area, and could provide a relatively untouched nature respite for nearby residents.

Citing social enterprise City Sprouts, which has made farming more accessible and attractive to the layman, Mr Ng said something similar could be done with the village, with a focus on fishing.

“The land will also be put in better use socially and economically, as compared to its restrictive access now,” he added.

Heritage blogger Jerome Lim, who runs The Long and Winding Road, was a little less sanguine, saying: “Even if the place can somehow be kept, its charm would eventually be lost.”

LAST OF ITS KIND?

Mr Ho Yong Min, founder of The Urbanist Singapore content platform, said there are “practical realities” that cannot be ignored – such as constraints in land-scarce Singapore, and how spaces like the Seletar fishing village are “not always formalised or built with long-term safety in mind”.

Yet preserving such spaces is what helps Singaporeans appreciate the diversity of the country’s heritage, which goes beyond shophouses and monuments, said the heritage educator.

The fishing village, in particular, “reminds us that our nation’s story is not only urban and modern, but also shaped by everyday communities who depended on the sea”, said Mr Ho.

But he also said heritage and development should not be seen as an either-or.

“The real question is not whether to keep or demolish, but how to integrate such spaces meaningfully into our future landscape, whether through adaptive reuse, selective preservation or creative interpretation.”

Mr Cai, the MP, described the activity at the fishing village as a throwback to practices, knowledge and traditions of coastal communities in the past.

"In terms of alternatives in the northeastern section, we have a jetty at Halus. But that serves a more commercial purpose, while this one is more of a community," he said.

Mr Cai said that even if the authorities allocate a new space for the Seletar fishing community, its members – most of them seniors – may find it difficult to move.

"There's also the question whether there are any younger fishermen who are interested to continue," he added.

As a fisherman at Seletar, who has plied his trade for 40 years, told CNA: “I’m a rare breed.”

“Nowadays, young people don’t want to do this kind of job,” said the 63-year-old, who introduced himself as Mr Bah Lak. “Most want to work in the office with aircon.”

For now, despite lingering uncertainty and the sense that any day could bring notice, Mr Bah and the dozens of other weather-beaten fishermen and boatmen continue to go about their routines.

They are a picture of calm and serenity, like the village that represents possibly their last physical anchor to the only lifestyle they have known.

“If the government says leave, then we’ll just leave,” said Mr Tan, the retiree.

From there, the options are to either find another place to moor their boats, or call time altogether.

In the area, there is the modern Punggol Marina, which would cost easily 10 times as much to dock, Mr Tan noted, concluding: “If there’s nowhere else to go, then I will just scrap the boat.”

If and when his time at Seletar comes to an end, Mr Toh, the caretaker’s son, is likely to move his operations to the Lorong Halus Jetty in Pasir Ris – so long as he can continue fishing.

“I was born in a kampung … I think in the 1970s, when I was about 14 and I hadn’t even gone to National Service, I already started fishing,” he said.

“I really like this place, but if they really want to chase us away, then there’s nothing I can do. That’s the way life is.”