What It Takes: Sprinting to the top in athletics - with Shanti Pereira

In the first part of a series 'What It Takes', where CNA journalists spend time with people to see what goes into becoming a top performer in their field, Matthew Mohan trains with sprint queen Shanti Pereira.

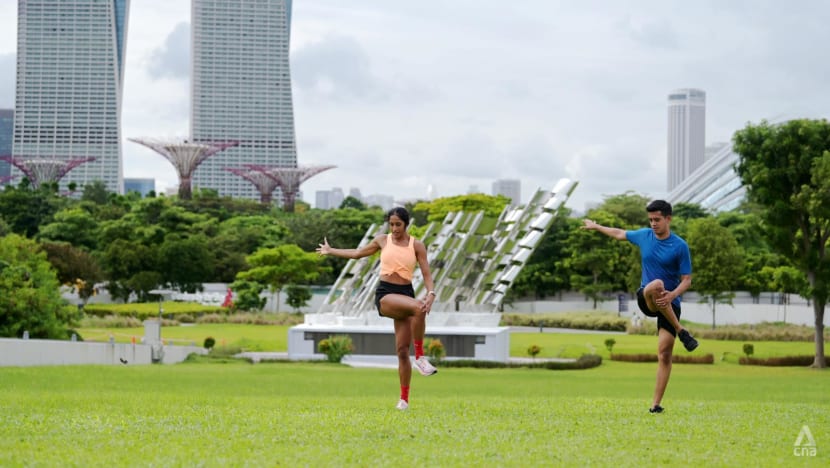

CNA's Matthew Mohan during a training session with sprinter Shanti Pereira. (Photo: CNA/Marcus Mark Ramos)

SINGAPORE: I crumple onto the bed after a long hot shower. Everything hurts.

Three sessions into a week-long training stint with Shanti Pereira, the effects were already beginning to show.

My thighs were throbbing, my shins were aching, and my feet were hurting. Even the simple act of bending over to pick something up was a chore.

And I still had two more days to go.

SMALL DETAILS MATTER

When you're at the top of your game, the margins of victory can come down to the finest margins. So fine, that effective use of an elastic band in training can make a difference.

So, while much of my time training with Pereira was, not surprisingly, spent on aerobic exercises, I also found myself learning the importance of things like improving dorsiflexion, or the backward-bending motion of one's foot.

Proper dorsiflexion puts one's foot in an ideal position to absorb the landing and move into the next stride. This reduces the time spent in contact with the ground, allowing one to run faster and more efficiently.

Pereira helps address this by tying the band from her shoelaces to the top of her heel.

"If that will improve the dorsiflexion I have, it already cuts down a lot of time if I can do that with every single step," she explained after a gruelling session at Marina Barrage.

Such methods can make all the difference in the push towards gold-medal glory, especially in sprinting where margins of victory can be in hundredths of a second.

“Once you reach a certain level, there’s more focus on the 1 per cent. A lot of the work has already been done, so we are just trying to find the smallest of details because that could in turn determine reduction of time," Pereira said.

Each of her training sessions serves a particular objective, and each drill serves a specific purpose.

Her coach Luis Cunha typically “loads movements” during these sessions, adding weighted resistance so that Pereira executes her techniques in the correct way. The idea is that this becomes incorporated into her muscle memory when she runs.

One way she does this is by using resistance bands during acceleration drills. When I try them, being pulled back by the extra resistance feels awkward at the beginning, but as the days go on I feel like I am running faster and freer.

My form, however, still needs work, but this is something which needs more than a couple of sessions to fix and a lot more attention to the small details than there is time for.

But coaching isn’t an exact science, Cunha stressed.

There is a lot of research out there when it comes to sprinting, but not all of it is useful. In fact, coaching can be seen to be as much about art as science, he said.

"Every composer starts with the same notes. Every author starts with the same alphabet. All artists start with the same palette of basic colors. All chefs start with the same food ingredients. Then why aren't they all the same? The creative process play an important role," he said.

"Coaching is similar. The coach should not be different than the composer or the artist or a chef. The coach's palette is the human body expressed through movement."

PART OF A FAMILY

2023 was a career-defining year for Pereira as the 27-year-old wrote herself into the history books.

At the Hangzhou Asian Games, she won the women’s 200m final. This was Singapore’s first athletics gold medal since 1974, when Chee Swee Lee won the women’s 400m title. Days before, Pereira ended Singapore’s nearly 50-year wait for a track and field medal at the Asian Games, after she clinched a silver in the 100m.

In August, Pereira became the first Singaporean to make a World Championships semi-finals after a stellar showing in the 200m.

Pereira notched a sprint double at the Asian Athletics Championships in July and also became the first Singaporean woman to win both the 100m and 200m events at the same edition of the SEA Games in May.

The big meet for her this year will be the Paris Olympics, where she has already met the 200m qualifying mark.

She hasn’t accomplished it alone though.

Pereira has attributed much of her success to the support of her boyfriend, her family and her coach. And as I trained with Pereira over a week at the beginning of the year, I saw how vital Cunha’s contribution has been.

A sprinter who competed at the 1988, 1992, 1996 Olympics, Cunha is meticulous in his approach.

He often unfolds a deck chair at the side of the track, but during the time I spent training with him, it was hardly utilised.

Cunha was nearly always on his feet. Observing, instructing, motivating. He paid painstaking attention as his athletes trained, stepping in to correct them if movements were executed wrongly.

But this isn’t a dictatorship. It is a democracy.

Over the course of the week I saw the rapport Cunha has with his training group of athletes. They respect him, he respects them, but there was always room for good-natured fun.

“I believe in humour allowing you to work better. This is true in any environment of work. In this case, the athletes need to do things which are very hard,” he said.

“You need to feel that in your work environment (and) training group, you have connections, you have friends, you have relationships. I believe with that it is much easier to do the things you need to do.”

This is a sentiment which Pereira shares.

"What we do is very hard. It's very taxing on your body, very taxing on your mind. You have to have some ... element to make it bearable, manageable," she said.

"If you're in your head all the time for all the workouts, then it can be extremely draining. As you do this more and more often, it becomes way more intense. So you need some sort of humour ... It's just a very fun environment to be in while doing something very serious which is nice."

A former lecturer at the University of Lisbon’s Faculty of Human Kinetics, Cunha is passionate about what he does.

Over the course of the week, he shared tidbits on the mechanics of running, the science which goes into sprinting, as well as the various tools in his arsenal to improve athletes.

He can go on and on, Pereira told me with a laugh.

Generally, Pereira’s sessions can be divided into the umbrella of the “metabolic” and “neuromuscular”, the Portuguese coach explained.

The metabolic sessions involve speed and endurance, with an exercise time of between 15 seconds to 1 minute and a rest time between of 90 seconds to 20 minutes.

These sessions could be on various surfaces such as grass, the track, the slopes and even on the stairs. On the other hand, neuromuscular exercises involve a combination of speed and strength, with a focus on either one or both.

It is important that athletes understand why they do what they do, Cunha said.

“I have my principles. If you want people to follow (you), to have the motivation to follow, to have the belief in you, in the process, you have to explain things,” he said.

“Just telling them to do the things without explanation … I don’t think that’s the best way to work. The athletes need to buy what you are selling, they need to believe in you.”

Pereira's training group consists of a number of national athletes including fellow sprinter Elizabeth-Ann Tan, 400m hurdles national record holder Calvin Quek and 400m national record holder Zubin Muncherji.

"When you have people running with you, it's a great push, you want to be better than each other. There's a competitive spirit in what we're doing every day," said Pereira.

"But it's also just (about) forming a nice little ... family."

I experience the warmth of the group as well as they welcomed me to their sessions, and gave me tips as I struggled along.

THINKING BIG PICTURE

While much of the attention in Pereira's training is on finessing many small things which can add up to make big differences, that does not come at the expense of the core physical techniques.

A sprint can be divided into acceleration, maximum velocity as well as speed endurance, Cunha explained. And for our first session of the week at Kallang Practice Track, the focus was on the first two phases.

With Pereira in her "general preparation" phase in the week I joined her, the focus was more on volume than intensity.

If I needed any reminder of how out of depth I was, all it took were the warm-ups during that session. Introduced to a whole gamut of stretching exercises, I floundered spectacularly.

The fire hydrant, designed to warm up one’s hips and activate the glutes, saw giggles from Pereira as she witnessed my hapless attempts at balancing.

On the punishing Marina Barrage slope days later, I was put through interval training.

The lung-busting workout involves 3 sets of 5 reps where we stride uphill within the allocated time. For Pereira, this starts with a rep of 15 seconds, then 30 seconds, and then eventually 45 seconds.

Like any coach, Cunha has a stopwatch hanging from his neck. But he also has an app where he can splice together clips of his athletes to compare their running form and execution.

"As a coach you should focus on what will make the athlete better at their sport, not better at drills or stronger at lifting weights," he said.

"95 per cent of drills have no transfer to skill so what is the attraction? There is so much good evidence and practice today in nonlinear pedagogy to guide us so don't be seduced by the allure of drills. Drills do not equal skills."

I am not spared from his analysis. After one particular sprint, he eyed my gangly run and remarked half in jest that I had given up.

At the same time, Cunha says it is important not to lose sight of the big picture.

"It is easy to get lost yourself in a small meaningless detail and lose sight of the ultimate objective. Instead, you should look for connections, step back and look at the rhythm, tempo, and flow of the movement," he said.

"It is not about individual muscles or small parts of a movement, it is about how everything links, syncs and connects in a coordinated manner to produce smooth flowing and fast movement."

What goes on off the track is equally important as well, emphasised the sprinter. She calls it a "24/7" job.

“A big part of it is definitely the training. The effort that I put in, the timings that I clock and stuff like that. But it’s the rest of the time which is just as important, if not more important,” she said.

“It’s getting your body ready for all these incredibly intense sessions. Being able to do that, to make sure your body recovers properly requires consistency, requires discipline.”

This can boil down to the smallest of things such as the time she eats and the time she sleeps.

Cunha has a general principle for his athletes where they abstain from eating, drinking and using their phones close to sleeping time.

“Just being strict with your routines ... is really, really important. Maybe some people may see that as not a big deal, but to athletes it’s a really big thing,” said Pereira.

When it comes to her diet, the sprinter practises intermittent fasting. She has two meals a day, lunch and dinner. On top of vegetables, much of what she eats is protein-based - chicken, tofu, eggs.

Pereira adds carbohydrates such as pasta in some meals, but only in a maximum of one meal a day to limit her carbohydrate intake. She also tries to cut down on as much sugar as possible.

PLANS A, B and C

Less than two hours before our brutal second session, I received a text from Cunha: “I hope to train at Marina Barrage.”

The text seemed oddly unspecific, I thought to myself. Would we or wouldn’t we train there?

The reason for the uncertainty then became clear.

“It can be tricky, especially when you want to utilise a lot of different venues,” Pereira explained.

“We just always have to be prepared, have a plan B. If plan A doesn’t work out, we go to plan B. If plan B doesn’t work out, we go to plan C. Over the years, we’ve just learnt and adapted to these situations.”

On that day, the rain lashed down in the late afternoon and our session on the slick steps leading to the Singapore Sports Hub had to be cut short. Pereira and her training mates headed to the Singapore Sports Institute gym instead.

Pereira has come to accept this unpredictability.

“There are even cases where we show up, it’s training time but it starts to rain and the lighting warning comes on. There is no choice and we have to delay training and go to another location,” she said.

“(It is about) just accepting that that’s part of the process.”

The overcast sky did eventually clear up on Wednesday, and I was rewarded with a generous dose of vitamin D as I huffed and puffed up the grassy knoll. As Pereira found shade under an umbrella, I gasped for breath.

If I thought sprinting up an incline were bad, Saturday’s training session was the worst. It was a session focused on speed and speed endurance where an inclined non-motorised treadmill left everybody on the floor and gasping for air.

As I recovered, I checked in with Cunha on how I did over the past week.

“You tried your best and yeah, it was okay. But if you ask me if you have enough talent to run a certain time, you need to be prepared for an honest answer from me.”

"It's hard to follow along with the training because it's so specific and it's also so intense," added Pereira.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time with Cunha and Pereira, as well as their openness to share the knowledge that goes into becoming a champion.

"As a coach, you should know what matters and focuses on what matters. One of the elements that really matters most is relationships ... the human element," said Cunha.

"In today's world of instant information and big data it is easy to forget that the numbers, data, measurements are one-dimensional, we coach people who are multidimensional. We should develop trust and working together with the athletes to guide them to grow athletically and personally."

Pereira's dedication to her craft is clear.

From the way she trains to the way she lives her life, this is an athlete determined to go faster. She gives each and every training session her absolute all and despite the relentless physicality of the challenge, Pereira goes about the sessions in good spirits.

While sprinting is not for me, it suits Pereira extremely well, and she isn’t stopping anytime soon.

This is an athlete at the top of her game, ready to take on the world. And my short time with her has shown just how and why.