5 key issues to watch out for in Baku’s COP29 global climate change talks

United Nations-led climate talks in Azerbaijan will be critical for promoting momentum across a wide range of green policy areas.

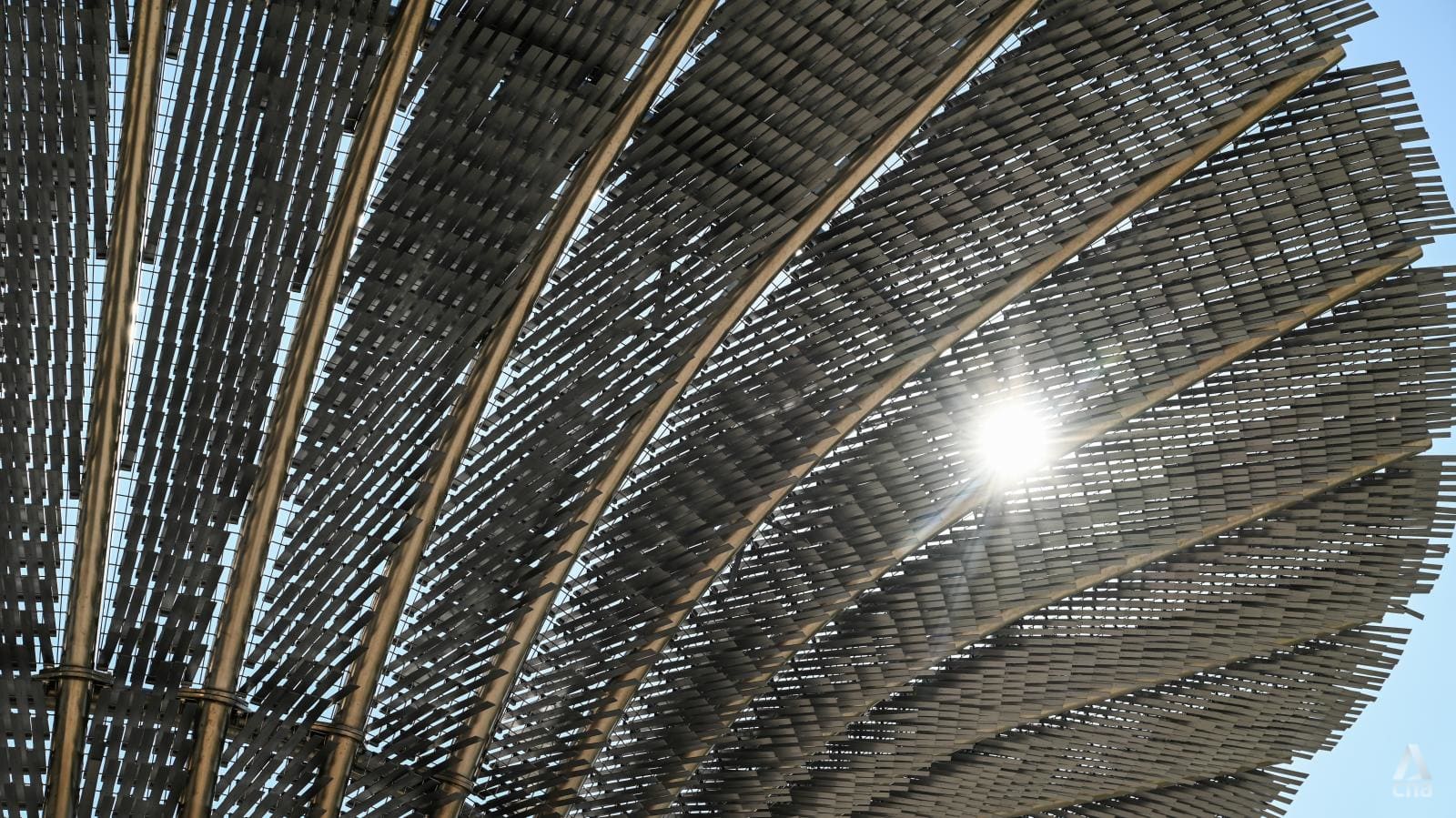

Baku is a city built on the wealth generated from fossil fuels. (Photo: CNA/Jack Board)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BAKU: Azerbaijan will be the centre of the climate change universe over the next fortnight, as it plays host to the 2024 United Nations (UN) Conference of Parties (COP29), another critical juncture for progress on key issues.

The COP is the supreme decision-making body of the UN when it comes to assessing progress in dealing with climate change.

World leaders, government negotiators, global financiers and industry heavyweights will begin talks in the capital Baku early next week, the latest round of high-level climate conversations to try and slow down temperature rise and transition the world’s economy to something greener and more sustainable.

Beyond the lofty overarching goals, focus will be honed in particular on mobilising the eye-watering amounts of public and private money needed to stave off climate calamity.

From the host’s perspective, the intention of the summit will be to “enhance ambition and enable action”, according to COP29 President-Designate Mukhtar Babayev.

There will be obstacles and sticking points. In the background, regional conflicts in Europe and the Middle East again threaten to undermine a multilateral system that is wholly dependent on consensus.

Negotiators will be on the clock - the summit starts on Nov 11 and is meant to close on Nov 22 - while in the background, scientists continue to warn that the planet’s vital signs are in bad shape and time for marked progress is imperative.

While attendance at COP29 is not expected to reach the 100,000 over delegates that were seen at COP28 in Dubai last year, this edition still looms as an important moment in climate talks.

Here are five key issues to pay attention to when COP29 commences.

1. SHOW US THE MONEY

Azerbaijan’s COP leadership is unabashed in its desire to make finance the central pillar of the talks. Its summit agenda is centred around money.

“Whether we like it or not, finance will be at the core of this year's climate negotiations,” COP29 CEO Elnur Soltanov told CNA. “Finance cannot be understood in abstract terms. Finance is there to enable action.”

Perhaps of most importance will be the negotiations around the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). This financial framework is designed to replace the US$100 billion in climate finance that developed economies had pledged in 2009 to provide to poorer nations every year by 2020.

By and large, those funds have not been delivered, prompting an attempt to overhaul an import pathway for finances to reach the countries that need climate support most.

That original pledged amount was arbitrary and not connected to actual needs of other countries but it had become a benchmark collective commitment.

Its effectiveness was widely questioned - especially by developing nations - whose needs have increased year on year, “highlighting the need for a more robust and effective financial mechanism”, according to the World Economic Forum.

Lead negotiators on the NCQG have said that the funding needs are in the trillions of dollars every year.

“We need enablers, we need means of implementation. We have finance, technology and capacity-building, and finance definitely is the most important thing out there,” Mr Soltanov said.

Who will give money, in what form and how much - in transparent and accessible ways - will all be negotiated further in Baku, amid calls for an escalation in urgency from the UN.

Growing the Loss and Damage Fun which was operationalised in Dubai for countries bearing the worst of climate impacts, will also be a key focus.

US$700 million was pledged to the fund last year but various research estimates that developing countries actually need hundreds of billions of dollars annually to properly address the loss and damage issue.

There are still issues surrounding how the World Bank hosts the fund, the integrity of the board and arrangements to ensure money is easily accessible.

Additionally, there will be a push to close the wide gap on funding for adaptation, the ability for countries to handle and live with climate impacts. It is an area long overlooked compared with funding for climate mitigation efforts and the World Bank is aiming to equalise the money going into both areas in 2024.

A 2021 report by Climate Policy Initiative found that only 10 per cent of climate financing was directed to adaptation.

“International climate finance must grow up, step up, and scale up, to meet this moment,” said Mr Simon Stiell, the executive secretary of UN Climate Change in a speech at an event hosted by the Brookings Institute, a Washington DC-based non-profit organisation, last month.

“In times like these, there is a temptation to turn inward. So let's instead choose the game-changer path ahead – the one that recognises that bigger and better climate finance is entirely in every nation's interests, and can deliver results everywhere,” he said.

2. TEMPERATURES OUT OF HAND

The planet is in worse shape than 12 months ago, scientists say.

Global temperatures have continued to increase, with surface and ocean temperatures both hitting record highs. Average temperatures made the 12 months between September 2023 and August 2024 the hottest year-long period ever, 1.64 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Agreement is aimed to keep temperatures within 1.5 degrees Celsius above these levels.

Heat records were broken in 19 countries, including Laos and Cambodia.

Concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane - a much more powerful pollutant in terms of heat contribution - are at all-time high levels in the atmosphere as fossil fuel production has continued to rise.

Climate change has also been strongly linked to intensified droughts, hurricanes and flood events across the world in 2024.

In the six months following COP28 last year, the damage estimates from extreme weather cost US$41 billion globally, highlighting the need for collective action on solutions, adaptation funding and improved mitigation efforts at COP29.

3. BYE BYE TO FOSSIL FUELS?

Central to Azerbaijan’s presidency of COP29 will be to lead the world’s shift away from a fossil-fuel powered future.

But oil and gas are the very resources that have driven the country’s prosperity for generations. And the modern-day reliance on them continues; those sectors account for an estimated 90 per cent of its exports and half of total gross domestic product.

Just this year, Azerbaijan president Ilham Aliyev said that oil was a “gift from God”.

For three consecutive years, an oil-producing nation has led the summit, following the United Arab Emirates last year and Egypt in 2022.

Last year, for the first time, the final COP agreement included wording about fossil fuels, calling for "transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner".

“30 years to get to the beginning of the end for fossil fuels”, the European Union noted at the time, referring to the three decades of COP summits, started in 1995.

The statement was a reflection of the steep opposition and lobbying that had derailed efforts to wean off the polluting fuels at previous meetings.

But there was no declared “phase out” or “phase down” of fossil fuels decided in Dubai, leaving the world’s polluters carte blanche to continue their operations.

The same arguments over phrasing can be expected to dominate discussions and could once again stymie the final agreement between nations in Baku.

4. THE SHADOW OF WAR

In the year since the Dubai summit, war has intensified and spread in the Middle East. Conflicts are ongoing in Ukraine, Sudan and Myanmar.

Given the COP process is reliant on cooperation between countries and requires consensus to make a formal declaration, the breakdown in trust is seen as a strong impediment to planet-saving action.

“Usually, climate negotiations have been insulated. But, this level of tension is unprecedented in modern times,” said Dr Jennifer Allan, a senior lecturer in international relations at Cardiff University.

“Resources are going to defence budgets and attention is anywhere but climate.”

These clashes have other impacts, beyond government-to-government relations. They are significant contributors to emissions - military operations in Gaza are estimated to have contributed substantial greenhouse gas emissions.

Including future rebuilding efforts, the conflict could end up causing the equivalent of 61 million tonnes of CO2 - more than the annual emissions of 135 individual nations, according to researchers from the United Kingdom and United States.

Conflict and climate change are also tightly entwined phenomena, feeding each other. As one gets worse, the other is prone to intensify as well.

“You have specifically a double burden. So countries affected by conflict are also, to a large degree, highly exposed to climate change, making life for the population incredibly difficult,” said Mr Florian Krampe, director of studies, peace and development at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Baku organisers have called for COP29 to be a “truce COP” and coincide with a one-month global ceasefire, while it will also emphasise peace as a significant theme for the first time.

5. WRAPPING UP CARBON RULES

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement has been a lingering issue for nearly a decade now.

It covers the rules and frameworks for international carbon markets, which can be used by countries to meet emissions-reductions targets and make achieving those goals cheaper.

At COP29, facilitators are hoping to finalise the mechanisms that can then lead to the buying and selling of carbon credits under a set framework.

For instance, highly polluting countries could purchase credits - permissions to emit more than otherwise permitted - from countries that have gained extra credits from measures such as restoring their rainforests.

Some of these initiatives are already underway in pilot form or through regional or bilateral agreements.

Singapore has signed bilateral carbon offset trading agreements with both Papua New Guinea and Ghana.

For the first time, delegation heads will be involved in Article 6 talks directly, an indication of the emphasis on finally concluding negotiations on this matter, which have been ongoing since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015.

Right now globally, there is a lack of rigour and centralised multilateral frameworks on how carbon markets work. That has stifled the flow of money into them and given rise to schemes that do not drive real emissions reductions, akin to greenwashing.

Negotiations are complex, technical and political. Issues such as unclear methodologies for counting credits, reporting rules and the risks of double counting credits have all combined to slow down progress on this key article.