Fiji's plans to uproot cyclone-vulnerable communities threaten indigenous identity, say locals

Fiji has developed an ambitious national policy to manage the potential relocation of hundreds of villages due to climate change. But ties to land and culture are delicate challenges for the country to overcome. CNA dives into the dilemma in the second of a three-part series on how Pacific island-nations are fighting climate change, and the lessons they offer.

Sea level rise is a danger for many Fijian communities. (Photo: Jack Board/CNA)

SUVA, FIJI: On the ever-shrinking beach that curls around the ancestral village of Vunisavisavi lies a dramatic symbol of both hope and turmoil.

An enormous banyan tree has been toppled in recent years. Powerful winds and waves wrenched its roots out of sandy foundations, leaving its broad trunk lying prone.

Children climb and play on the tree. It has become a vantage point for young ones to scan the open water on the horizon.

It also neatly forms a physical barrier between the ocean - a growing source of danger - and the village, an increasingly insecure refuge.

Locals here say it was planted more than half a century ago. Yet, even in its fallen state, roots exposed to the salt and spray, the tree lives.

As climate change threatens to uproot communities here, the banyan is a metaphor for their fight to remain in place.

Vunisavisavi is a village on edge. It was one of many in Fiji earmarked to be possibly relocated to a new place within the country due to the worsening threats posed by the fast-warming planet, including devastating regular tropical cyclones.

In 2017, the government identified 830 potentially vulnerable communities and a further 48 communities that might urgently need planned relocation.

It has led the Fijian government to develop what might be the world’s most extensive, dedicated set of national guidelines to usher in an era where internal displacement is an unavoidable reality.

It is a policy - called the Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for Planned Relocation - that the world will be watching, as nations everywhere increasingly face the same challenges.

Nearly nine million people in 88 countries and territories were living in displacement due to disasters at the end of 2023, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.

The SOP was approved by the current Fiji government last year, and it aims to lay out the requirements for communities before they can be relocated.

It is a “living document”, with “a human-centred and human rights approach”, the guidelines state. The document outlines the various stages and phases of identifying risks, consulting communities, managing land, balancing cultural considerations, funding and evaluations.

Key components of the guidelines centre on the need for initial public consultations and community hearings, transparent decision making, grievance redress mechanisms and options for partial relocations.

Relocating these communities is a hugely complex and emotional process, which the SOP aims to manage.

These are moves often beset by sadness - a feeling that something is lost during the process. Community ties are a powerful force in Fiji and it is climate change threatening to undermine them.

“When a community relocates, it is not simply about moving to a new place, to a new house,” Mr Sitiveni Rabuka, the prime minister of Fiji and minister responsible for Climate Change wrote in the SOP document’s foreword.

“When a community relocates, they take with them their culture, their history, and their expectations for a better life. Therefore, a decision taken to relocate should never be taken lightly.”

Every time another disaster strikes this island nation, there is a risk of even more villages being added to the relocation roster, and an increasing likelihood of unique local identities being lost, according to locals and experts.

LOOKING FOR BETTER DAYS

Fiji is experiencing climate impacts at a greater pace and intensity than many other parts of the world. Ocean heat in the region is increasing by up to three times the global average, while sea level rise is also threatening low-lying islands and coastal communities.

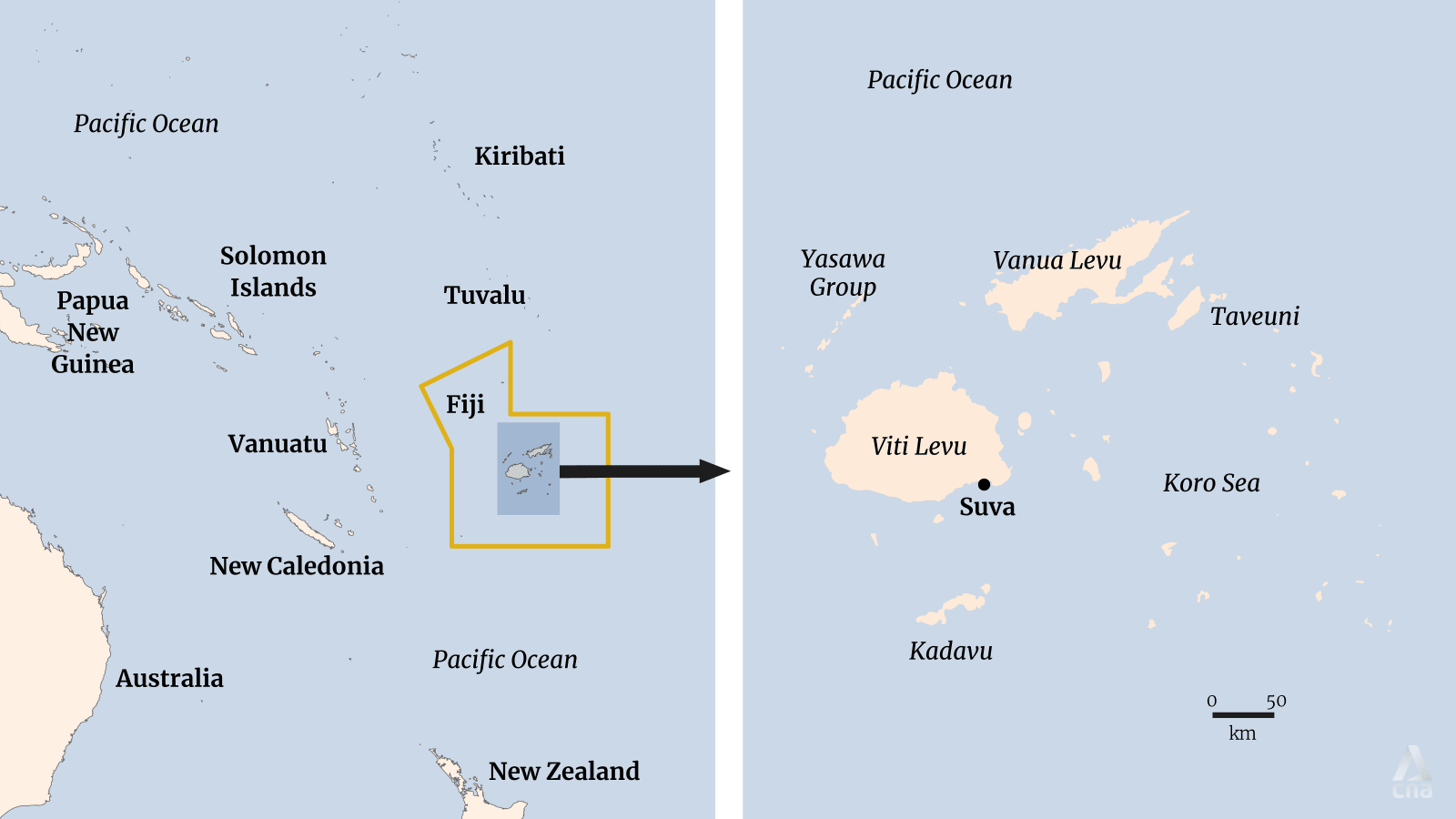

The country comprises 382 islands and islets, with a population of just under one million people. It is regularly impacted by tropical cyclones - in 2016 Cyclone Winston killed 44 people and caused US$1.4b in damage.

Four years later, in December 2020, Cyclone Yasa was a category 5 cyclone that destroyed about 8,000 homes and caused some US$250m in damage to infrastructure, livelihoods and agriculture.

Even today, communities are still rebuilding from that storm event. A few hours drive from Vunisavisavi, the village of Cogea still carries the physical and emotional scars that Yasa dealt out.

This part of Fiji, on the isolated southern coast of the country’s second largest island, Vanua Levu, is normally idyllic.

Freshwater streams flow gently towards the sea, shaded by rich, tall canopies of dense lowland rainforest. The sea is a striking blue, shallow and enriched by vast coral reef systems. Local villages that dot the shorelines and mountain sides are immaculately kept and ordered.

Mostly, small rippling waves gnaw at the sandy shorelines. But the waves have grown violent in the past. And they will be again. The locals here have seen it.

In Cogea, a village of 138 people a few kilometres inland from the coast, Cyclone Yasa brought devastating flooding. The settlement is encircled by water, which has become prone to fast rises when the weather takes a turn.

Mr Rusiate Senicevuga, the village’s headman, built his home to be cyclone-proof. He underestimated the power of Yasa.

“In the morning when we woke up, we were speechless. I was shocked. The house I relied on for our safety during cyclones was gone,” he said.

“Some villagers who were living in tents were supposed to be there for three months only. Because of the extent of what happened to them, some were still in tents for two years.”

Landslides pummelled the mountain areas around the village, which was partially submerged, with multiple houses destroyed. Crops that local people rely on to survive were decimated, adding to regular food security concerns as agriculture and fishing efforts fail more often.

“We continue to be reminded of what Cyclone Yasa took away from us. A lot has changed for us. We are very scared because of those experiences,” he said.

Climate Conversations: What's the impact of climate change on the Pacific islands?

Cogea’s residents are slated to be relocated due to the ongoing threat of inundation. Fear overcomes many of them whenever the clouds turn dark these days,” Mr Senicevuga admitted.

A nearby site, almost within view of their existing village, has been earmarked for the move. But despite the anxiety of staying in place, moving has also caused division.

“Our original foundation is very sentimental and special to us. This is where our ancestors lived. It is not an easy thing for me to see the young people agree to this relocation,” said Ms Silina Tinai, a village elder.

“I am worried about the future generation of Cogea. There will be change here. Not only today but every day and every year ahead. For me, it pains me that we are about to leave this village,” she said.

This sentiment is common across the country. Deep cultural roots bond people to the land of their ancestors.

But for Mr Senicevuga, the community will never find peace of mind until they move to higher ground. The realities of climate change demand it, irrespective of the powerful ties to the past. For now, they are stuck in limbo waiting for funds to fully construct their new homes.

A moving date remains unclear.

“In my opinion, at least for my family, what they experienced during Cyclone Yasa will never be erased from their memory. The only better days for the future generation will be at the new site,” he said.

DOMESTIC REFUGEES

Critics of the relocation guidelines as they currently exist say culture is an overlooked factor behind official decision making.

The SOP strives to ensure that community social and cultural structures “are not dismantled as these bind the community together and is their social safety net in times of hardship”.

That means, for example, ensuring that communal spaces are maintained and the hierarchical order that exists within traditional villages is respected.

But there is conflict between indigenous knowledge and sensitivity and government bureaucracy trying to manage the practicalities of urgent and expensive projects, according to Mr Simione Sevudredre, the founder of Sau-Vaka Cultural Consultancy.

“For stakeholders, for governments, who are engaged in relocating communities due to climate change, it is very easy to overlook the spiritual intangible dimensions, because these are the invisible threads that anchor and bind our community to a place,” he said.

“Our indigenous spirituality is very old. It's tied and pegged to the land. And relocation is not an easy thing to do overnight. Because the ways of living, values and ethics have been derived from nature, from the environment, and from us, as humans, as custodians.”

These values can manifest physically in everyday life, through the worship of ancestors’ graves, in social hierarchies and respect to elders, or in the inherent knowledge about where and how to grow or find food.

Mr Isoa Talemaibua, the permanent secretary for Fiji’s Ministry of Rural and Maritime Development, the office charged with overseeing the SOP, said the relocation task force has been focused on a consultative approach and “getting people to buy in”.

“Through the consultations, there are people who say no. We've been finding it difficult for some,” he said.

“It's a painful process - people leaving behind what they've been attached to for years, or generations and generations. And most of them cry over their land. It's a form of attachment that really touches their mind, soul and body. So, it's a painful jump for all of us.

“But we need to convince them for the betterment of everyone. Climate change is real. It has affected few in the past but now it seems to affect the whole of Fiji, due to sea level rise and other associated issues.”

He said the department hopes to improve on its ability to handle delicate matters going forward. “We are just getting into it. There may be teething problems,” he said. Finding the necessary finances to streamline the guidelines and make them as effective as possible is still a challenge.

A trust fund with an annual allocation of US$5 million used to pay for the relocations has been established and supported by both the New Zealand and German governments but far more will be needed.

The cost of moving one village alone - in the example of Nabavatu in 2021 - was US$2.5 million.

Fiji remains an active voice on the global stage calling for the faster mobilisation of green climate finance from polluting nations to pay for such schemes.

In 2018, the government said the country would need approximately US$4.1 billion over a 10-year period to strengthen its resilience to climate change and in 2022 identified the need for a total investment of US$1.98 billion to achieve its NDC targets and transition to a net zero economy.

Globally, the sums required by climate-vulnerable states are eye watering.

“Experts have estimated that over US$4 trillion will be needed annually by 2030 to manage the impacts of climate change. There needs to be a herculean effort to mobilise financing and investments that are accessible and cost effective in delivering benefits to all,” Mr Rabuka said at global climate talks at COP28 in Dubai late last year.

There are already examples of where relocation has caused problems. Three Fijian villages and two settlements have already been moved, before the adoption of the SOP, with mixed outcomes.

Complaints in those places about social issues arising, a lack of careful planning in the new locations, spiritual detachments and land conflicts are well documented.

The example of Vunidogoloa, the first village to be moved in the country back in 2014, is now a prominent case study of what not to do - villagers were left far from their ancestral hunting grounds, with incomplete infrastructure, which led to social and health issues. These are questions and issues that other countries in the world will be contending with increasingly over the coming decades. Fiji is just the early mover at a national scale.

Mr Sevudredre said learning in this space is crucial to preserving any unique culture and the people tied to it. That can start by listening.

“Perhaps stakeholders need to consider involving the community themselves from the beginning? And asking the right questions about how indigenous knowledge can inform the decisions rather than coming in and making a blanket decision,” he said.

“It’s a shared pathway that must be done in consultation with whichever community. The people, the owners, have the knowledge. They know best. They just need to be heard.

“The clock is ticking if there is no consideration to the unseen, invisible, intangible dimensions. We run the risk of creating more lost people, more unanchored people. We can become like refugees within our own country,” he said.

HOME OF A KING

Vunisavisavi is the home of a king.

It is the land of "Tui Cakau", one of Fiji’s three paramount chiefs, a title passed down through fifteen generations. Today’s descendants are the guardians of sacred land and are fulfilling an age-old promise to protect it.

But the central section of Vunisavisavi village now appears like a wasteland. Water rushes through - from the ocean and the mountains - during storms. Some people have moved their houses already to keep their feet dry.

And although the entire village is meant to be shifted from the shoreline, resistance to that plan is strong.

“This province will not be known if this place is deserted. We are now attending awareness workshops on climate change but for the elders here, their duty to their chief is still more important,” said Ms Mariana Sarawaqa, a village leader.

“They cannot move. Relocation is not part of their plan. We know if we relocate, we will lose our identity permanently,” she said.

Father Ben Salacakau, a clan member of the community, is a vocal advocate against the government’s plan to safeguard villages by moving them. Instead, he wants a greater focus on adapting and defending.

While he acknowledges the scale of the problem across the country, trying to tackle it all at once is not proving sustainable, he said.

“The government has very short-term, quick solutions. I like to say that they operate like a sprinkler. The water is going everywhere but you only get a few drops. Nothing can really make an impact,” he said.

“I think they should work on a viable system, really develop a place to be functioning and self-sustaining and then go to the next one.”

In the shallows in front of Vunisavisavi, young mangroves are slowly rising. The community is doing what it can to build barriers from the waves, and say they hope a sea wall can be constructed sometime in the future.

“I’ve told the children, if you don’t do this, maybe in the next few years, you will not be living here. You will have to move away because this place will be washed away. There will be no more Vunisavisavi. If you don’t act, we will lose this place,” said Ms Sarawaqa.

Like the banyan tree persisting in the face of the elements, so too are these Fijians holding on tightly to their land, their roots taking grip in the soil, trying to persist and grow.

“We will do whatever we can do to keep this place.”