Poland faces strain on resources as it grapples with sustaining aid for Ukrainian refugees

Millions have fled Ukraine since the outbreak of the war with Russia, with many heading over to neighbouring Poland.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

WARSAW: Russia's invasion of Ukraine has led to what has been called Europe's biggest refugee crisis of the 21st century.

Millions have fled the country, with many heading over to seek refuge in neighbouring Poland.

But with no signs of the war ending soon, Poland's own capacity to sustain aid for refugees is slowly thinning.

The war hit the two-year mark recently. Russian President Vladimir Putin had first sent his army into Ukraine on Feb 24, 2022.

SCHOOLING IN A FOREIGN LAND

Close to half of the Ukrainian children who fled to Poland currently attend local schools, such as Szkoła Podstawowa nr 361 in Warsaw.

Children of Ukrainian refugees can attend school for free in Poland, though some opt for online classes to keep up with the Ukrainian curriculum instead.

In Poland, the students get to pick up the local language, meet other children, and also understand Polish culture.

One such student, Yelyzaveta Sedelnikova, told CNA that it was tough at the beginning as she did not speak a single word of Polish.

“Later, when I started to learn Polish and improved my language skills, I could talk to my friends and teachers in Polish, and now I feel comfortable,” she said.

Out of about 850 students at the school, more than a hundred of them are Ukrainian.

New classrooms were built to take them in, and Ukrainian teachers who escaped the war were also recruited to help them through the transition.

The school’s director Tomasz Remiszewski told CNA the Ukrainian community has made a big impact.

“We wanted to integrate these kids both ways — Polish with Ukrainians (and) Ukrainians with Polish — to share their points of view, to teach each other (and) to show their roots,” he said.

ADAPTING TO ANOTHER LIFE

Since the invasion two years ago, more than 6 million refugees have fled Ukraine.

About a million settled in Poland, which responded by providing various forms of support, including family benefits.

Ms Liudmyla Chumachenko took her son Yan, 13, and crossed the border with just a suitcase in hand when the war broke out.

"We got help when we just crossed the border. It was a one-time assistance of 300 zloty (US$75),” Ms Chumachenko told CNA.

“But then when we came here, we started to get 500 zloty per month since I have a young child. Starting January, it's increased to 800 zloty per month. That’s really good money."

Ms Chumachenko misses her husband and elder son, who both stayed behind to fight in the army.

She is making a new life for herself and Yan in Warsaw, and the duo have been living with their Polish host for nearly two years now.

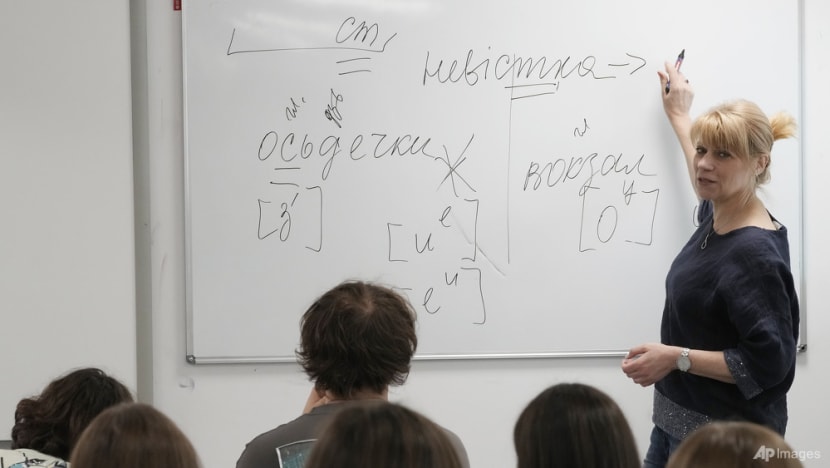

"Before the full-scale invasion, I was working as a teacher's assistant at a kindergarten, and I want to get the same job. But first of all, I have to learn Polish,” she told CNA.

There are special schools designated for adults by the Polish government, she said.

“We can visit these classes to learn Polish and then get a job, so I am doing that.”

As they adapt to life in Poland, Ms Chumachenko and her son Yan’s desire to go back home to Ukraine is slowly ebbing.

"I want to stay here. I don't want to go back and see lonely abandoned houses in ruins after the bombings,” Yan told CNA.

“I want to see my father, grandmother, brother and cat again. I want to bring all of them here to Poland."

THINNING RESOURCES

At the start of the war in 2022, Ukrainians fleeing Russia's attacks were welcomed in Poland with open arms.

With no signs of the war ending soon, however, Poland's capacity to sustain aid for refugees is under strain, with Ukrainians requiring housing, jobs and education.

In a refugee centre in Warsaw’s city centre run by the Uniters Foundation volunteer group, queues of those seeking help are long and donations increasingly scarce.

Elderly Ukrainians who cannot find jobs especially find themselves in limbo.

Uniters Foundation co-founder Viktoriia Batryn told CNA: "If you are 65-plus years old and you don't know the language, you cannot work here. So how can you live your normal life when you are just sitting and waiting? What next?

“All these people are hoping to go back, but a lot of them lost everything, like home."