Cubicles as homes: Can Hong Kong solve its housing issues?

Only 7 per cent of developed land in Hong Kong is allocated for residential use, with more than 220,000 people living in cage homes and waiting an average of six years for a public housing unit.

Ms Au, 67, has lived in a cage home for nine years. Her diabetes has worsened since she moved in. (Photo: CNA/Chow Yin Shing)

HONG KONG: The kitchen walls are damp with grime and wires tangle haphazardly across a paint-peeled ceiling. Ventilation fans, caked with dust, turn weakly in Hong Kong’s humid summer.

But no amount of wind can mask the heavy sense of resignation in this Mongkok cage home.

"I can’t sleep without the fan, because I can’t open the window. You just need to endure all these when you are living in this kind of place,” said a 75-year-old resident who only wanted to be known as Mr Lau.

He is among about 15 residents packed into a narrow fourth-floor apartment, each to a cubicle.

Everything he owns – clothes, a rice cooker, food – is crammed into shelves above a thin mattress.

A few pods down is a 67-year-old woman who also wanted to be known only by her surname, Au.

“As long as there is some space in the house, the landlord will take every inch to sub-divide a room. He literally used up all the space here. In fact, he divided our kitchen into four rooms,” she told CNA.

The space is not just small - it can get dirty and poses both a health and fire hazard, said Ms Au, who has lived there for nine years.

"The environment is so bad that I can't even describe it. If the place gets too dirty, rats and cockroaches can come up,” she said.

The flights of steps leading up to her home have also become problematic for the diabetic, whose condition is worsening.

But Hong Kong's low-income have no choice but to live in such conditions: It is the only affordable option in a city of high property prices.

They don't exactly come cheap either, setting them back by HK$2,500 (US$318) a month.

It's a reality that more than 220,000 people in Hong Kong wake up to each day, while waiting for an average of six years for a public housing unit.

HOUSING NOW A PRIORITY

Only 7 per cent of developed land in Hong Kong is allocated for residential use.

Last year, Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office Director Xia Baolong urged the government to scrap these homes by 2049.

Chinese president Xi Jinping renewed this call in July when he visited Hong Kong for the 25th anniversary of the city’s handover to the mainland.

Hong Kong’s new chief executive John Lee has made housing a key priority, appointing two task forces to look into housing and land supply issues.

They are due to submit their first report within 100 days of the new term - which falls on Saturday (Oct 8).

An existing short-term solution to Hong Kong’s housing crisis lies in a 2018 government initiative: Transitional housing.

It is catered to low-income residents living in inadequate environments, like subdivided flats or cage homes.

Under the scheme, public and private developers can convert their old facilities into public housing.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) can also tap on a HK$11 billion (US$1.4 billion) fund to build and run these projects.

As of August, the government has identified land to shore up 21,996 transitional housing units, of which 5,418 are already in operation.

These units range from 152 sq ft to more than 300 sq ft, depending on the size of the household.

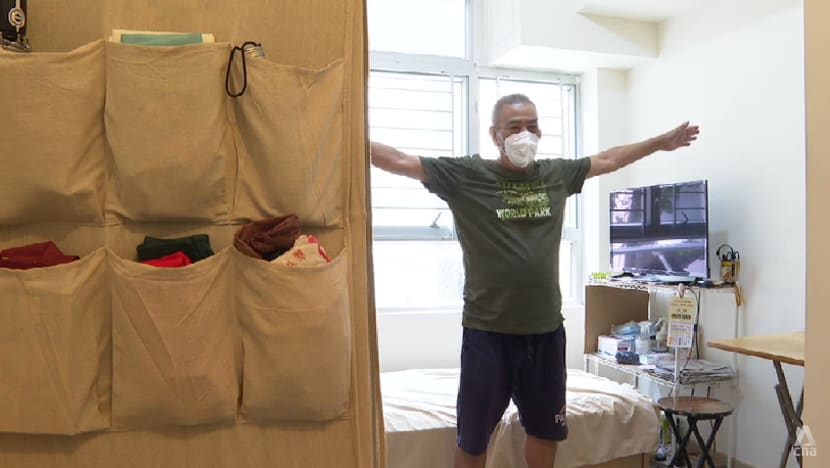

Mr Tsao Shin Fu’s household is among 140 in a transitional housing project called Ying Wa Street Social Housing.

It’s a big improvement for the 77-year-old, who used to live in a cage home in Mongkok.

“I was always bitten by lice during my five years in a cage home at Mongkok," he said. "(The space) was slightly bigger than two feet. As I lived on the upper shelf, I couldn’t stand up. I even had to eat my dinner on the bed.

“My home right now is much bigger and more comfortable. I can do some exercises after I wake up in the morning and also at night.”

There are windows with an outdoor drying rack next to his single bed, where he can hang his clothes. A few steps away is a kitchenette, and an ensuite bathroom. It’s clean and private - luxuries he couldn’t afford in the past.

The Lee administration wants to build more of such houses, faster. But it's not that simple.

AN IMPERFECT SOLUTION

Among the issues is who takes responsibility for constructing these transitional homes, said Ms Sze Lai Shan, deputy director of local NGO Society for Community Organisation (SoCO), which manages such housing projects.

“NGOs take up the responsibility of building the transitional homes. But since the government can work with the Housing Department, Housing Society and Urban Renewal Authority, they should be responsible for construction,” she said.

“Afterwards, the NGOs can take up the operation and management roles.”

The two-year tenancy limit under the scheme brings another set of problems. Some projects allow residents to renew their lease - but this is not guaranteed.

“It will take a very long time to be allocated a public housing unit, especially for applicants who are single men. That can take more than 10 years. So, we hope the government allows extension(s),” Ms Sze added.

Mr Tsao lives in relative comfort now, but the uncertainty of his future remains.

“I’ve been waiting for a public housing unit for three years. I don't know when I can get it. If I can’t get it after two years, I’ll probably sleep under the bridge. It would be miserable if I were to move back to the cage home," he said.

Mr Tsao's concerns are part of reasons why many end up on the streets.

Data from the Social Welfare Department shows there were 1,580 registered street sleepers between 2020 and 2021 - a 22 per cent increase from between 2018 and 2019.

The most common reasons for people ending up homeless include the inability to pay rent due to unemployment, and failure to find affordable accommodation.

Street sleepers are among the city’s most vulnerable groups. Once off the social ladder, it is hard to climb back up.

“They have very weak social capital so when they encounter difficulties, there is no network that can support them. And since they are isolated and marginalised, they are less familiar with social resources or welfare system,” said Ms Yeung Tsz-Ning, the head of programmes at NGO ImpactHK.

She added that the government needs to consolidate efforts across its housing, welfare and health bureaus to tackle the crisis.

ImpactHK conducts weekly night walks across the city, where volunteers and social workers give out food, water and hygiene products.

It’s a simple affair, but for the homeless, it’s usually a chance to get the help they need.

ALTERNATIVE MODELS

ImpactHK has a shelter for the homeless, as well as co-living apartments which serve as an alternative to the government-funded transitional housing projects.

Under this programme, ImpactHK matches clients to a three- to five-bedroom apartment. Residents pay rent for their own rooms and share a living room and kitchen.

They cater to residents who fall between the cracks, like 35-year-old Ah Chiu.

He doesn’t fit the bill for the government’s scheme, which requires applicants to have lived in a subdivided unit, waited for public rental housing for at least three years, and be employed among other criteria.

Ah Chiu just applied for public housing two months ago and has never lived in a subdivided flat.

While he is happy to have a roof over his head, he wants to become more independent.

"I hope that after one year of staying here, I can learn to take care of myself. ImpactHK’s original intention is to help us when we encounter difficulties. They don’t wish to see everyone depending on NGOs,” he said.

With the demand for transitional housing on the rise, ImpactHK's Ms Yeung urged the government to make its policy more inclusive.

The first step? Redefining what it means to have a home, she said.

“Transitional housing offers the homeless a stable, safe space to live. They don’t have to be on 'survival mode' or worry about theft or food. With stability, they can re-plan their lives.”

Additional reporting by Jojo Chan.