‘Does it need to be so loud?’: Indonesia’s earsplitting sound horeg trucks leave communities divided

Business is booming for mobile entertainment trucks called sound horegs in East Java. But as near-130 decibel levels shatter safety limits and cause houses to crack and tempers to flare, they’ve been labelled “sinful” by some local authorities.

A man in a monster costume dances to music played by a sound horeg truck at a parade in Jeru village, Malang, East Java, Indonesia on Aug 30, 2025. (Photo: CNA/Wisnu Agung Prasetyo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

MALANG, East Java: As a convoy of about 30 trucks rolled into the tiny farming village of Jeru in East Java’s Malang regency last month, residents began streaming out of their homes with a mix of anticipation and apprehension on their faces.

The trucks, with sound systems stacked higher than rooftops and festooned with strobe lights, lasers and LED panels, were so wide they could barely squeeze through Jeru’s winding roads. They were so tall they came perilously close to clipping overhead power lines.

The convoy soon got Jeru’s celebration of Indonesia’s Independence Day underway with the thump of drumbeats and wobble of basslines that grew louder with each passing minute.

Jeru’s residents had spent more than a year raising nearly 1 billion rupiah (US$60,000) to hire the mobile entertainment vehicles, known locally as sound horeg (pronounced “hor-uh-g”).

“This is what we wait for all year,” said Adi, 19, excitedly as he danced with his friends. “Our village is quiet and boring, but for one night every year, it’s alive.”

Each truck was kitted with a diesel generator big enough to light 10 small houses, powering sound systems that can reach more than 130 decibels - roughly the volume of a jackhammer or an ambulance siren.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), people can listen safely at an average of 80 decibels for up to 40 hours a week. If they turn the volume up to 90 decibels, they can only listen safely for up to four hours a week. Eighty decibels is about the volume of a doorbell, while 90 decibels is the equivalent of a shouted conversation, according to the WHO.

In Jeru, the convoy peaked at 127 decibels, going by a decibel meter CNA used.

Besides being loud enough to damage one’s eardrums, such volumes have been known on occasion to crack windows, chip wall plaster and shake roof tiles loose.

This has stirred tensions between enthusiasts and detractors that sometimes erupt into fights, underscoring the deep divide the phenomenon has created within communities in East and Central Java, where sound horegs are popular.

This has prompted the authorities to step in. On Jul 14, Indonesia’s most influential Islamic body, the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), issued an edict declaring sound horegs haram, or sinful.

The council cited both physical harm caused by the speakers’ deafening volume and moral concerns, noting that the events often feature rowdy, sometimes drunken, crowds and dancers in revealing outfits which it deemed inappropriate.

In the weeks that followed, some cities in East and Central Java moved to ban sound horegs altogether, citing the edict and growing public unease.

Yet in the rural heartlands, where these trucks remain a rare form of entertainment, they continue to operate legally.

The authorities in East Java province have tried to strike a middle ground. A regulation was introduced on Aug 6, setting a 120 decibel limit for when these sound horeg trucks are stationary, such as during a concert, and 80 decibels for when they are on the move, like in a parade.

But with volume caps still exceeding what health experts and many locals deem acceptable - and with enforcement still patchy - sound horegs continue to spark controversy.

BIGGER SPEAKERS, MORE EXCITED CROWDS

People in Jeru and other parts of East Java have staged parades and carnivals for generations to commemorate their village founding, give thanks for bountiful harvests or celebrate the country’s independence.

Because they needed a mobile sound system for parades, people began using pick-up trucks in the 1980s and 1990s to ferry around speakers powered by a small car battery.

“Eventually, the speakers got bigger and sound (produced) got louder, which got the performers and the crowd more excited,” David Stefan Laksamana, a second-generation sound systems provider, told CNA.

This triggered a race for louder, larger and more dazzling mobile entertainment vehicles.

By the early 2000s, the speaker rigs got so large that sound system providers like David began ditching pick-ups in favour of dump trucks capable of hauling tonnes of equipment.

Around the same time, people started calling these trucks sound horeg, which means “trembling" in some Javanese dialects, said David.

“Perhaps, (for some people) loud sounds can trigger their adrenaline. They love that trembling sensation in their body,” David said.

But the “real reason” for dialling up the volume, he reckoned, is because “there is competition between residents (of different villages), a competition between organisers to see who can stage the loudest (carnivals)”.

Muzahidin, another sound horeg provider, said inter-village rivalries are putting pressure on sound providers to be bigger and louder.

“Personally, I don’t think the sound needs to be that loud. The speakers will break, as will all these lights and electronics if we keep pushing (the volume) to the max,” he told CNA.

“But what can we do? The organisers will complain if we’re not loud enough.”

And it pays to be the loudest.

Muzahidin’s company, Brewog Sound, for example, has become something of a household name in his East Javan home city of Kediri and Malang, with loyal fans eagerly awaiting when one of its 10 horeg trucks is scheduled to appear.

“We are booked solid until the end of the year. Some of my guys have been on the road for three months straight,” he said, adding that he has been landing gigs as far as hundreds of kilometres from Kediri.

David’s company, Blizzard, which is based in Malang regency and operates six trucks, is also fully booked months in advance. “Sometimes, organisers will put a downpayment for next year’s gig after this year’s event ends,” he said.

Both Brewog and Blizzard charge 25 to 35 million rupiah per truck for a one-night event. With each truck performing up to three gigs a week, they can quickly recuperate the 1 billion rupiah investment needed to build and outfit one of these behemoths.

But competition is getting fiercer, said David, who is also chairman of a Malang sound system providers’ association.

“In Malang alone, there are at least 1,200 sound horeg trucks registered with our association,” he said.

“But there is room to expand. Central Java is starting to include sound horeg as part of their festivities and I believe other provinces will follow.”

HOUSE FELT "ABOUT TO COLLAPSE"

The sound horeg trucks, however, are an earsplitting nuisance to some people.

When two sound horeg trucks went past Siti’s house on the outskirts of Malang city in July, “it felt like the whole house was shattering and about to collapse”, said the 56-year-old.

“I immediately got out of the house and begged them to stop because my house was falling apart. But they refused to quiet down and instead called me names,” she said.

“These trucks are just too loud, and they seem to get louder every year,” complained Jeru resident Sutarni, 72, grimacing as she covered her ears with her palms during her village’s Independence Day celebration last month.

Iriana Maharani, an ear, nose and throat doctor from East Java’s Brawijaya University, said that the higher the decibel, the shorter its safe duration becomes.

According to WHO, at 120 decibels, the duration for safe listening is 12 seconds per week. “Beyond that, it is already damaging to the ears,” said Iriana.

The sound horeg parade in Jeru lasted six hours and covered a distance of 4.5km, which is about the average, according to sound horeg operators CNA spoke to.

Complaints about sound horegs have also surfaced in the neighbouring city of Batu, said Abdullah Thohir, chairman of the local chapter of the Indonesian Ulema Council, MUI.

“Our congregation has been complaining about these sound horegs. They were too loud. They damaged people’s hearing and properties. The people involved were also unruly and had no respect for elders who told them to stop,” he told CNA.

“People also complained that some (members) of the crowd were drunk and the dancers were wearing skimpy outfits and danced in ways that were inappropriate. Mind you, these were events held in the middle of crowded neighbourhoods and villages attended by children.”

Abdullah took the matter to the provincial office of the Islamic body.

“It turns out that Batu (chapter of MUI) is not alone. (MUI members from) other cities and regencies are also complaining (about sound horeg),” he said. “After careful consideration, the East Java chapter of the MUI declared sound horeg haram.”

On Jul 16, two days after the MUI edict was issued, police in the city of Malang banned sound horeg or any other high-powered sound system “to preserve order and people’s comfort.” On Jul 20, Batu City police issued a similar ban.

Although sound horeg is no longer allowed in the two cities, the other 36 regencies and municipalities in East Java have resisted outright prohibition, opting instead to limit the trucks’ volume and dimensions.

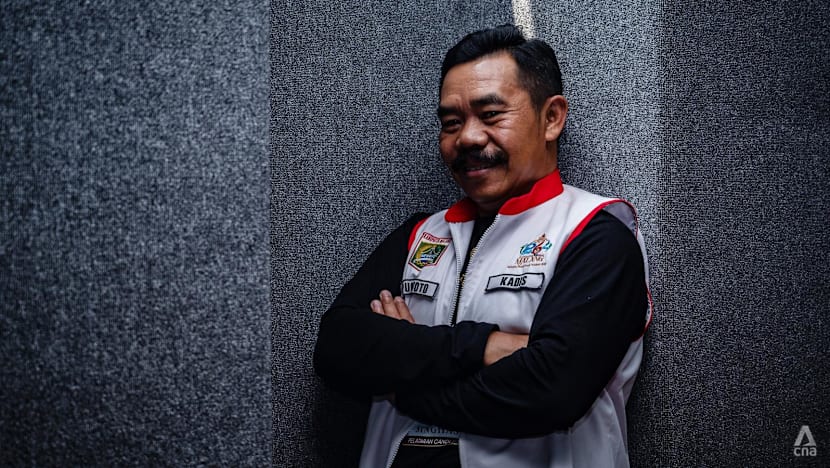

“Just like any events, there are economic activities stimulated by these sound horeg parades,” said Purwoto, chief of the Malang regency’s tourism and culture agency. The regency has a different administration from Malang city.

“The sound rental companies are benefitting (from these events) but so are costume makers, food vendors and parking space owners,” Purwoto said.

“But such parades must not be discotheques on wheels. They must reflect the traditions, norms and cultures observed in Malang.”

FINDING A MIDDLE GROUND

On Aug 6, the East Java government issued a regulation limiting how loud and how big these trucks can get, as well as where and when they can operate.

When the trucks are in a parade and pass residential areas, their volumes must not exceed 80 decibels, the regulation stated. When they are stationary and used in a concert that is away from people’s homes, their volume is capped at 120 decibels.

Operators must also turn off all sound when passing hospitals, places of worship and schools.

Meanwhile, organisers are barred from serving alcohol or featuring “activities which defy religious values and norms.”

Although the province has stopped short of a blanket ban, Abdullah of MUI said the Islamic body views the regulation as “an acceptable middle ground.”

“We are happy that there is now a clear line which people shouldn’t cross. We are also grateful that alcohol, drugs, inappropriate dancing and other activities which are not in line with religious values are banned,” he said.

Operators also support the regulation.

“If you ask me, does it need to be so loud, I would have to say ‘no’. (It’s) the people who hired us (who) insist that we should be as loud as possible,” sound horeg operator David said. “Thanks to this regulation, now we have an excuse not to meet such demands.”

Enforcement, however, has been inconsistent. Although parade volumes are capped at 80 decibels, CNA found most trucks exceeding 100 decibels during the procession in Jeru on Aug 30, with at least two exceeding 120 decibels even while moving.

“The regulation is still new,” said Purwoto. “But in future, they will be tightly monitored for volume and size. Public safety must come first.”

To Iriana the ear, nose and throat doctor, the limits are still too high.

She has already noticed an uptick in patients that coincides with the rise of sound horegs, though no formal studies exist yet.

“There are limits to what our bodies can endure, and those limits shrink as we age,” the doctor warned.

“Some damage may be temporary, but with extremely loud sounds, the damage can be permanent. We need to protect our ears, because nothing can replace the quality of healthy hearing.”