Indonesia Elections 2024: Presidential candidates’ climate pledges vague, possibly counter-productive, activists say

Indonesia’s presidential hopefuls have backed the goal of net-zero emissions by 2060. But some of their proposals could do more harm than good to the environment, experts caution.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

JAKARTA: One has pledged “climate justice”, another wants to make Indonesia a “superpower” in biofuels and renewable energy, while the other believes in making remote villages across the vast archipelago energy self-reliant.

All three candidates vying for Indonesia’s top job have promised to fight climate change and cut carbon emissions ahead of the country's presidential and legislative elections on Feb 14.

But their vague proposals and lack of ambition have disappointed environmentalists, who want Indonesia’s targets to be raised beyond what sitting president Joko Widodo has put in place.

“No one is giving a clear and concrete outline on how to address the environmental issues Indonesia is currently facing. No one is setting the ambitious target needed to handle the climate crisis,” Mr Leonard Simanjuntak, the Indonesia director of environmental group Greenpeace, told CNA.

Besides being out of line with efforts to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, some plans announced by the candidates may, in fact, do more harm than good to the environment, experts said.

Under Mr Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, Indonesia has pledged to cut its emissions by nearly 32 per cent on its own, or by 43.2 per cent with international support by 2030. These targets, announced in 2022, are slightly higher than its earlier Paris Agreement pledge.

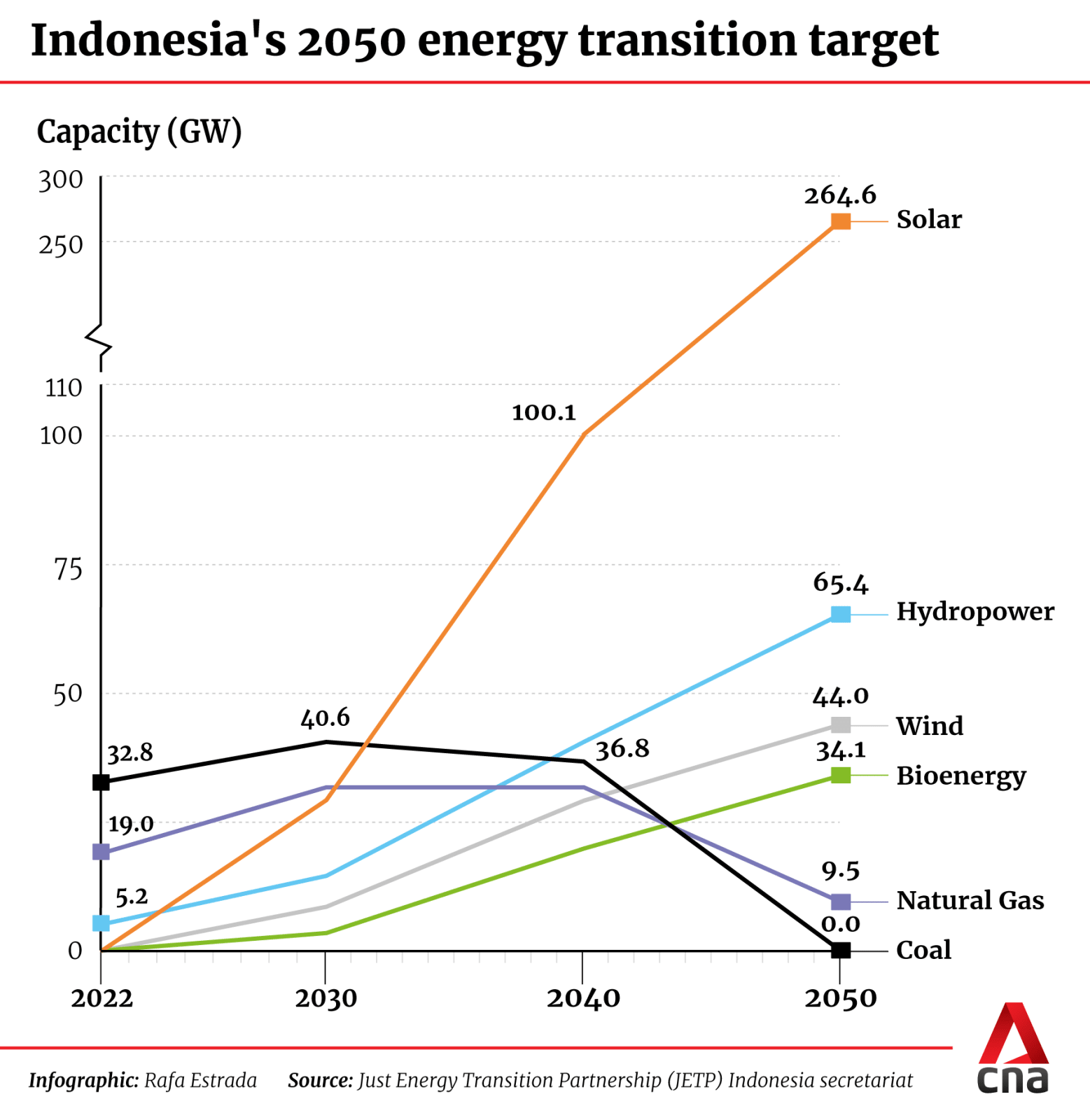

Indonesia has also pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060 or earlier, which means it will absorb as much carbon as it emits. It plans to do so by retiring all its coal-fired power plants by 2050 and deploying more clean energy sources like solar farms and wind turbines.

The country – Southeast Asia’s largest economy and the world’s largest coal exporter – currently derives 57 per cent of its energy from coal, which is the dirtiest fossil fuel. Indonesia's energy sector emitted 600 million tonnes of carbon-dioxide in 2021.

How Mr Widodo’s successor continues to steer Indonesia’s energy transition will have a far-reaching impact.

REACHING NET-ZERO

All three candidates – former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan, defence minister Prabowo Subianto and former Central Java governor Ganjar Pranowo – have said they will remain committed to the goals set by Jokowi if they become Indonesia’s next president.

.png?itok=icPRlxJi)

However, their plans to achieve these goals differ.

Mr Anies and his vice-presidential running mate Muhaimin Iskandar plan to closely monitor the carbon emitted by factories, smelters and power plants. They have pledged to retire coal power plants, especially those in Java and Bali, early.

Although they have promised to increase the share of renewables in Indonesia’s energy mix, they have not specified a target. Indonesia’s current goal is for renewables to make up 23 per cent of its electricity mix by 2025, up from 14 per cent in 2021, according to the International Energy Agency.

They have also promised incentives to encourage communities to participate in clean electricity generation, which could be on-grid or off-grid.

Their two rival teams have also announced net-zero targets.

In addition, Mr Ganjar Pranowo and his vice-presidential pick, Mr Mahfud MD, have set a target for renewables in Indonesia’s energy mix – 30 per cent by 2029.

The Ganjar-Mahfud plan to achieve this involves thousands of “energy self-reliant villages” across Indonesia. These villages will generate their electricity solely or partially from the sources available in their regions, which could range from geothermal and solar, to natural gas and hydropower.

Although some climate activists agree with a focus on community-based clean energy programmes over large-scale projects, Mr Leonard said the Ganjar-Mahfud team’s “energy self-reliant villages” plan is, in itself, not enough to get Indonesia to net-zero.

“The big consumers of electricity are in the big cities,” he said. “We need a more ambitious strategy because we are heading to a climate catastrophe.”

SOVEREIGNTY THE FOCUS FOR PRABOWO-GIBRAN

Mr Prabowo Subianto and his running mate, Mr Gibran Rakabuming Raka, have affirmed climate targets made under Jokowi’s administration, including early retirement of coal power plants.

The pair’s climate and environment proposals are generally focused on Indonesia’s sovereignty, such as self-sufficiency in energy, food and water. They believe Indonesia has the potential to become the world’s “superpower” in biofuels and renewable energy.

“By increasing our biofuel production, we can reduce (oil) imports, increase the production of our palm oil and it is more environmentally friendly,” Mr Gibran said on Jan 21 during a vice-presidential debate on environment, energy and food security.

The pair also want to promote the use of bioplastics, which are made from biomass sources like vegetable oils and fats. Bioplastics have been touted as an eco-friendly substitute for plastic, but experts caution they are not a real solution as they can be composted only in carefully controlled conditions. If bioplastics end up in landfills, they could cause environmental harm, as plastics do.

Boosting Indonesia’s biofuel production could also mean more deforestation, benefiting big palm oil companies at the expense of the environment, noted Mr Anggi Putra Prayoga, a campaign manager at Forest Watch Indonesia.

“(The plan) will harm Indonesia’s natural forests,” Mr Anggi told CNA.

Indonesia produced 18.4 million tonnes of palm oil in 2022, according to the Indonesian Palm Oil Association (GAPKI), 47 per cent of which was used to produce biodiesel.

Meanwhile, Indonesia’s fuel consumption was 69.7 million tonnes in 2022, which means millions of hectares of forests would have to be converted into oil palm plantations if the country wishes to boost its biofuel output.

The country is already the world’s largest producer of palm oil and, according to the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture, has 16.8 million hectares of land used for oil palm cultivation.

Although there has been a downward trend in deforestation since 2018, Indonesia is still losing about 100,000 ha of forest and peatland a year, Greenpeace Indonesia recently noted. Indonesia has the world's third-largest area of rainforest, after the Amazon and Africa's Congo Basin, which is home to many threatened plants and animals.

The current government’s plan is for Indonesia’s forestry sector to be a carbon sink absorbing more carbon than it releases by 2030. But in an analysis released in December, Greenpeace Indonesia found that in areas already allocated for industrial uses, tens of millions of hectares of natural forest are at risk because of the lack of strict regulations to protect them.

DOWNSIDES TO DOWNSTREAMING

Both the Prabowo-Gibran and Ganjar-Mahfud tickets have promised to continue the country’s drive to be a key player in the production of batteries for electric vehicles.

Indonesia holds the world’s largest nickel reserve with an estimated 21 million tonnes and Jokowi has been ramping up the mining and processing of nickel ore during his tenure to meet global demand.

Both pairs have promised to expand Jokowi’s downstreaming policy, processing minerals at home rather than exporting them in their raw form, to other sectors.

But activists note that Jokowi’s downstreaming policy has led to the establishment of dozens of coal-fired power plants to feed power-hungry smelters and mining operations, not to mention widespread deforestation and pollution.

“Downstreaming is producing carbon on a massive scale,” said Mr Fanny Tri Jambore, a campaign manager at the non-profit group, Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi).

The Anies-Muhaimin team, on the other hand, has promised to balance economic development and environmental protection in its manifesto. They pledged to bring “climate justice” by protecting vulnerable but underdeveloped communities against the impacts of climate change.

But they have provided no further details on turning this idea into actionable policies, activists said.

Mr Leonard of Greenpeace said Indonesia needs a leader who can deliver on promises to tackle climate change.

“The world is watching whether Indonesia can meet its own goals delivered during COP, particularly as so many countries are providing or promising grants and loans for Indonesia to meet those goals,” he said, referring to the annual climate talks called Conference of the Parties that review how nations are implementing their targets.

Under the Just Energy Transition Partnership, nine countries – members of the Group of Seven (G7) plus Denmark and Norway – have pledged to lend US$20 billion for Indonesia’s decarbonisation efforts.

“We need (Indonesia’s next leader) to have more ambitious and concrete plans on environmental protection and transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy. We need more than rhetoric,” said Mr Leonard.