Indonesia’s textbook rewrite delayed to November as critics double down on call to scrap project

The books are meant to become Indonesia’s historical reference for students across all education levels there but critics warn that it sanitises the nation’s past.

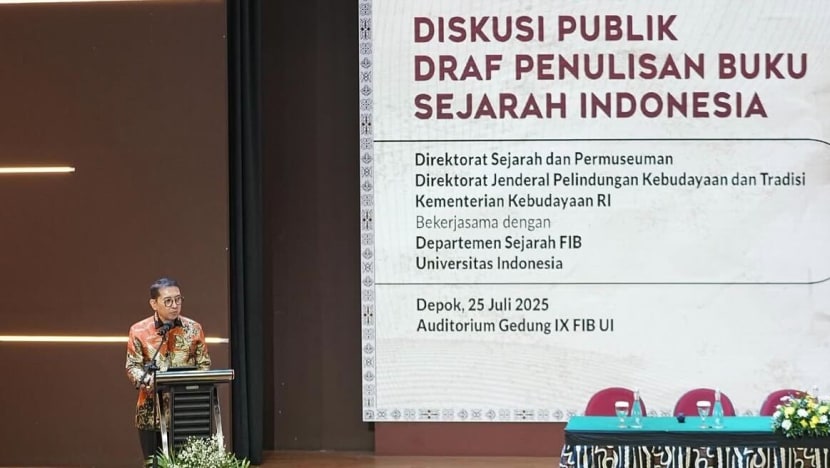

Indonesian Culture Minister Fadli Zon speaks at a public forum on the national history book project at the University of Indonesia in Jakarta. (Photo: Instagram/@fadlizon)

JAKARTA: The Indonesian government has postponed the launch of its controversial national history book project by about three months, though critics still call for it to be scrapped entirely.

Initially slated to be launched this Sunday (Aug 17) - which is Indonesia’s Independence Day - the 10-volume book is now slated to be released on Nov 10 to coincide with the country’s National Heroes Day.

The day commemorates the Battle of Surabaya - a fierce conflict in 1945 between Indonesian nationalists and British forces.

The history rewrite project has been widely criticised by historians and human rights activists for “sanitising the nation’s past” and omitting major human rights violations.

According to local media, the books are meant to become the country’s historical reference for students across all education levels there.

“Our plan is to still launch the book this year … because this is part of a series of events to celebrate 80 years of Indonesian independence,” Culture Minister Fadli Zon was quoted as saying by Jakarta Post on Aug 10.

Fadli, who is part of President Prabowo Subianto’s Gerindra Party, said that the postponement would give more time to “perfect the draft”, adding that it may require two or three more rounds of public discussions before publication.

According to Fadli, these public discussions and forums have been conducted openly at four local universities: University of Indonesia in Jakarta, the State University of Padang in West Sumatra, Lambung Mangkurat University in Kalimantan and the State University of Makassar in Sulawesi.

“We will continue (these public discussions) with other history enthusiasts and historians,” he said, as reported by Tempo.

These discussions at universities have been ongoing since late July, according to Jakarta Post, which the minister said has generated “various interesting suggestions” that would enrich the work.

Last month, Fadli reportedly dismissed claims that the history rewrite project was being rushed, adding that his ministry’s goal of completing the 10-volume book series by August this year is realistic.

“If people say it’s rushed, I don’t think that’s true. Everyone involved is a professional in their field so the timeline makes sense,” he was quoted as saying by Tempo at an online public discussion of the book’s draft on Jul 28.

An official from the Culture Ministry told Jakarta Post on the same day that the books are currently in the “editing stage by volume editors”.

“Hopefully, public input from these forums can help fill in any remaining gaps before it moves on to the general editor for final refinement,” said Restu Gunawan, the ministry’s director general for the protection of culture and tradition.

According to Fadli, the books are being written by 112 historians from 34 universities across Indonesia, including professors and veteran historians.

Speaking to reporters last month, the culture minister said that the project should have been produced much earlier.

“If we don’t write our own history, our youth may end up knowing more about the history of America or Europe than about Indonesia,” he said, describing the project as an intellectual gift to mark 80 years of Indonesia’s independence.

Among those who have urged the government not to rush the history rewrite project was Speaker of the House of Representatives Puan Maharani, who is also the daughter of Indonesia’s fifth president Megawati Soekarnoputri.

“Don’t be hasty, let’s re-examine the historical facts,” Puan earlier told parliament on Jul 3, as reported by Tempo.

According to the Jakarta Post, the 10-volume book will include everything from the latest archaeological findings on early civilisations in the archipelago up to the end of former president Joko Widodo’s second term in October last year.

Fadli had also sought to reassure the public that the history books “are not hiding anything” amid concerns of past human rights abuses that may be whitewashed.

Speaking at a parliamentary hearing last month, the culture minister had acknowledged the sexual violence which occurred during the 1998 riots in Indonesia but questioned the use of the term "mass rape", which he said "needs to be proven".

FRESH CALLS TO SCRAP THE HISTORY REWRITE

Meanwhile, there continue to be fresh calls for the project to be scrapped, with some activists claiming that it is an attempt by the government to “manipulate history”.

“We stand by our initial stance to reject the project, not just because of its lack of transparency but also for its attempt to manipulate history, especially the part that today’s administration does not seem to accept,” Dimas Bagus Arya, coordinator of the Commission for Missing Persons and Victims of Violence in Indonesia, told Jakarta Post on Monday.

He described the project as the “government’s attempt to sanitise the past”.

Echoing this, Marzuki Darusman, a human rights advocate representing the Indonesian Historical Transparency Alliance consisting of dozens of activists and historians, has also reiterated calls for the government to scrap the project.

“We accept this postponement only as a step towards the project’s complete cancellation by the government,” he said, as quoted by Jakarta Post.

Fadli, a close ally of Prabowo, came under fire for his remarks that the mass rapes were “all hearsay” and “rumours” in June.

Marzuki, who also led the 1998 fact-finding team established by former President BJ Habibie to investigate the mass rapes, said the government is aiming to “set history straight” according to its own version rather than uncover past crimes.

“This project continues to be problematic regardless of what the substance is because a state can never have a final say on history,” he added.

The unrest in Indonesia in 1998 arose from economic turmoil and mounting anger at former President Suharto’s authoritarian rule.

Chinese-Indonesians were targeted in riots that broke out in various cities in May that year, days before Suharto resigned.

According to media outlet Nikkei Asia, a 30-page draft outline of the rewrite project that has circulated online only included two out of 17 cases of gross human rights violations recognised by Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights,

Some of the omitted cases include events involving President Prabowo, according to Nikkei Asia.

Prabowo, a former general, was accused of orchestrating the kidnapping and forced disappearance of 22 activists critical of Suharto between 1997 and 1998, including 13 who are still missing today.

In a 2014 interview with Al Jazeera during Indonesia’s presidential race then which he eventually lost, Prabowo had admitted he helped abduct activists during the final years of Suharto’s regime, saying that he was acting under orders and that the kidnappings were legal at the time.

He was dismissed from the Indonesian military in August 1998 after evidence showed he had ordered the kidnappings. However, the current president has always denied that he was involved in the activists’ disappearances.