Political Islam: Hijab rules and segregated pools - religion reshapes social norms in Malaysia, Indonesia

In the third of a five-part series on political Islam in Southeast Asia, CNA examines whether regulations on "indecent clothing", betting and other social issues in Malaysia and Indonesia are hurting diversity for the sake of religious and political gains.

A group of students from a public elementary school in Bukittinggi, West Sumatra, Indonesia getting ready for their physical education class at a local stadium. (Photo: CNA/Wisnu Agung Prasetyo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

KUALA LUMPUR/PADANG: It was supposed to be an exciting day for Ms Jenny Hia. After six months of studying remotely because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the teenager finally set foot at Public Vocational School Number 2 in Indonesia’s Padang City in January 2021.

She was hoping she could meet new friends, but all she got were awkward stares from schoolmates and teachers.

The Christian teenager, then 16, was the only girl in school who did not wear the hijab, a Muslim headscarf meant to conceal a woman’s hair and neck and a mandatory garment for all female students at the school.

Over the next few days, Ms Hia was summoned by various school officials about her refusal to wear the item. One teacher even brought four Christian students, all of whom had decided to comply with the public school’s regulation, to put pressure on her to do the same.

But Ms Hia remained steadfast.

“Public schools are supposed to be open to people of all religions. The way we dress should not be according to one religion. Everyone should be able to dress however they want,” she said.

Her family took the case to Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights, putting a much needed spotlight on the plight of religious minorities in West Sumatra.

The case sparked a nationwide debate so fierce, three Indonesian ministries – the ministry of education, the ministry of religion and the ministry of home affairs – issued a joint decree on Feb 3, 2021 barring schools and regional governments from requiring students and teachers to wear “attributes of a specific religion”.

But three months after it was enacted, the Indonesian Supreme Court repealed the decree amid pressure from conservative Muslim groups and the customary council of the Minangkabau people, the biggest ethnic group in West Sumatra.

Three years on, Ms Hia’s case has faded from the limelight. The Supreme Court decision meant that the requirement for all female students to wear the hijab in West Sumatra, as well as other Indonesian provinces, is here to stay.

Her case is just one example of how increasing restrictions in the name of religion are upheaving social norms and liberties in Indonesia and neighbouring Malaysia.

Discrimination towards religious minorities has been on the rise in homogenous Indonesian provinces such as West Sumatra, where 97 per cent of the province’s 5.5 million inhabitants are Muslims.

“West Sumatra has become an icon of conservatism,” Mr Bonar Tigor Naipospos, deputy chairman of not-for-profit organisation Setara Institute for Democracy and Peace, told CNA.

To woo Muslim voters, politicians and public officials have been issuing Syariah-inspired regulations and decrees as well as discriminatory policies and programmes.

In 2005, then-Padang mayor Fauzi Bahar issued a decree mandating all Muslim students in public schools wear Islamic outfits. The same decree also required non-Muslims to “adjust their outfits” to the requirement but left no further explanation.

Schools were left to decide what the provision for non-Muslim students meant. Nearly all public schools in Padang interpreted the decree as requiring all female students, regardless of their faith, to wear the hijab.

“Spaces for non-Muslims to express their non-Muslim identities have indirectly become limited,” said Mr Sudarto, the founder of West Sumatra-based interfaith group, Inter-Community Study Group (Pusaka), adding that it has been happening gradually over decades.

The problem is not unique to West Sumatra.

According to New York-based rights group, Human Rights Watch, there are at least 120 mandatory hijab regulations and decrees issued by regional governments across Indonesia. Meanwhile, there are close to 150,000 schools across Southeast Asia’s largest economy which require students to wear “attributes of a certain religion.”

Ms Hia said after the incident, her school no longer forced her or other Christian students to wear the hijab. She graduated last year.

But what happened at Padang’s Vocational School Number 2 is the exception to the norm.

Activists also warned that the school’s decision not to enforce its policy – which has never been revoked – is fragile, especially as Ms Hia’s case fades from public memory.

RISE OF THE “MORAL POLICE”

In Malaysia, policies on modest clothing, checks on unmarried couples, the closing down of 4D betting shops, and religious “moral policing” by the authorities are making Ms Siti Kasim fear for her country’s future.

The lawyer is worried that the path of “Islamisation” taken by the country’s politicians will slowly and surely change the Malaysian way of life.

Miss Siti Kasim, an outspoken critic of Islamic religious authorities, said that the imposition of religion was becoming more and more rampant in the country, used and promoted by politicians.

“The problem is these people want to enact more laws to control us. Politicians allow this religious sort of morality to be imposed on us and we have to follow them. The governments are putting these laws in place. So, it is part of political Islam,” she said.

Kelantan and Terengganu states, which have shown the strongest support for the Islamist party Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) for decades, have come under the microscope for some of their policies regarding social practices. Critics say they were tantamount to moral policing.

Muslims make up more than 95 per cent of the population in states such as Kelantan and Terengganu, higher than the 63.5 per cent in Malaysia.

In July 2023 for example, an owner of a salon in Kota Bharu - the capital of Kelantan - was fined RM100 (US$ 21.20) for allowing her female worker to cut the hair of a Muslim male customer.

This incident occurred a month after a non-Muslim boutique owner was issued a summons for violating the council's bylaw on "indecent clothing" by wearing shorts in her shop.

The woman was pictured wearing a baggy t-shirt that covered her shorts.

She had committed an offence under Section 34(2)(b) of the Business and Industrial Trade Bylaws 2019, which states non-Muslim business owners and non-Muslim employees must wear “decent clothes”.

After the incident made headlines, the Minister of Housing and Local Government Nga Kor Ming said that the summons was cancelled following a discussion with the local council.

These bylaws that supposedly emphasise Islamic values were enforced and implemented by the Kota Bharu Municipal Council and also prohibit advertisements that do not cover the modesty of models.

Cinemas have also been banned in Kelantan since 1990 - the year PAS won the state - with various government representatives claiming over the years that cinemas could lead to social ills.

Terengganu, meanwhile, has banned women from competing in gymnastics events because of their non-Syariah compliant outfits. Instead, several of their Muslim women gymnasts were offered places to compete in the Chinese martial arts wushu event at the 2024 Malaysia Games.

“The moral police are pushing the boundaries until they get what they want. The majority of Malays, especially the young, have been indoctrinated to a certain way of thinking,” claimed Ms Siti Kasim.

Permatang Pauh MP Muhammad Fawwaz Muhammad Jan, who is with PAS, protested alcohol being sold openly at a mall in his constituency during the Chinese New Year celebrations last year.

Over the years, other politicians from PAS and religious groups have made headlines for their statements protesting Valentine's Day and Halloween.

In 2016, then-PAS Youth chief Nik Mohamad Abduh Nik Abdul Aziz said that Muslim youths should not celebrate Valentine's Day as it went against the teachings of the Islamic religion.

Even the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (Jakim) has over the years reminded Muslims not to celebrate the occasion as it is not part of Islamic culture.

More recently, Coldplay, Billie Eilish and Blackpink concerts held in Malaysia have not been spared either, with various statements by politicians saying that they would promote social ills such as LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) culture.

In May last year, Mr Nasrudin Hassan - a PAS central working committee member - called for the cancellation of a Coldplay concert in a Facebook post.

“Does the government want to nurture a culture of hedonism and perversion in this country?” asked Mr Nasrudin, adding that the concert would bring no benefit to “religion, race and country”.

The Facebook post was accompanied by images of lead vocalist Chris Martin holding a rainbow flag - which is used to represent the LGBT community - during a performance.

Related:

THE PRICE OF SPEAKING UP

Discriminatory policies in both countries do not stop at clothing or cultural trends.

Several regencies and cities across Indonesia’s West Sumatra also put the ability to read the Islamic holy book Quran – which is written in Arabic – as a requirement to graduate elementary school or enter junior high school.

Mdm Belvan Sihombing, a Christian who came to West Sumatra in 2022, said she was dumbfounded when her son came home from elementary school one day with homework on Islamic studies.

“My son was forced to learn about fiqh,” the mother of two told CNA, referring to the study on Islamic jurisprudence. “I went (to my son’s school) and talked to the teacher. Thank God they listened.”

But not everyone is willing to listen and the backlash for speaking up can be life-threatening.

Ms Hia’s father, Mr Elianu Hia, said he received countless death threats on Facebook and WhatsApp after his daughter’s case became national news.

“Some wanted to kill me. Some wanted to evict me from Padang City. I was worried (about my family’s safety). That was why I thought about moving (from West Sumatra),” said the 54-year-old father of six, adding that the case also affected his air conditioner repair shop, with many of his longtime customers too afraid to do business with him.

Mr Hia said he decided to stay after several government and law enforcement officials came to his house and ensured his family’s safety.

Also receiving death threats was Mdm Zubaidah Djohar, who was born and raised in West Sumatra but has since moved to Jakarta.

The 50-year-old poet and author spoke at an online discussion in 2021 in which she criticised schools, universities and public institutions in West Sumatra for offering scholarships and special enrolment programmes for people who could memorise the Quran.

She felt that the programmes discriminated against non-Muslim candidates who might have more skills and competence than students who could memorise the Quran, known in Islam as hafiz.

During the discussion, Mdm Zubaidah engaged in a heated debate with a local cleric and a member of the Indonesian Council of Ulamas, the country’s most influential Islamic organisation.

“People who felt they were the holiest and most righteous took offence at my criticism. They also took offence that I was wearing headscarves but I still show my hair and neck,” Mdm Zubaidah told CNA.

The poet said she received countless death threats after the discussion. Some conservative Muslims went as far as creating Facebook groups to discuss ways to assassinate her.

“I don’t want to go back to West Sumatra. People there will only listen to the elite few. Their words are worshipped while dissenting opinions are sidelined or even condemned,” she said.

RISE OF INTOLERANCE IN WEST SUMATRA

West Sumatra’s Solok Regency became the first area in Indonesia to issue Syariah-inspired regulations in 2001, requiring students to be able to read the Quran if they wish to graduate.

A year later, the same regency issued a regulation mandating the use of the hijab in schools, public offices and government events.

Both regulations do not mention an exemption for non-Muslims.

Human Rights Watch recorded that since 2001, more than 700 Syariah-inspired regulations and decrees have been passed across Indonesia. In some cases, the regulations were word-for-word copies of the ones issued by Solok Regency.

Mr Hardi Siswan, a politician and member of the Minangkabau customary council said the regulations and policies were simply a reflection of the norms and values observed by the people of West Sumatra and urged non-Muslims and migrants to comply.

“We have a saying, ‘wherever our feet are planted, from there the sky is reached’. Wherever we reside, we have to adhere to the laws and ways observed by the local people,” he said.

But Mr Sudarto of Pusaka disagrees. He believes public officials and the regulations they issue must be inclusive and accommodate everyone regardless of their religion and background.

“Can public officials who are financed by taxpayers’ money regardless of their religion, ensure justice for all?” he said.

“The basic feature of a democracy is diversity. Can they manage this diversity on the principles of equality and justice?”

ANALYST: ISSUES RAISED REVOLVE AROUND MORALITY

Similarly, political analyst and co-founder of Malaysian pollster Merdeka Center, Ibrahim Suffian, has observed regional regulations shaped by public morals considered sinful in Islam such as gambling, alcohol use, and khalwat (close proximity).

He said that these issues are technically not criminal in a civil sense but would be considered criminal under Syariah laws.

“I think so long as there is competition between the main Malay parties for the Malay electorate, they will always use Islam to try and obtain political support.

“Malays are for the most part Muslim and it is an important part of their identity. When there are conservative issues that supposedly incorporate Islam, they are trying to show that they are a party that can be trusted,” he said, adding that PAS was the main party at the forefront of political Islam.

All four states led by PAS have banned operations of gambling shops.

The northern state of Perlis shut its last 4D outlet in early March. It had been under Barisan Nasional (BN) rule until the Nov 2022 elections when Perikatan Nasional (PN) won power.

PN consists of PAS, Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu), and Parti Gerakan Malaysia (Gerakan), although the latter does not have any seats in the state.

According to news reports, there were six such shops in Perlis but all were shut down after the PAS-led government decided not to renew operating licences for these outlets.

Perlis State Housing and Local Government Committee chairman Fakhrul Anwar Ismail was quoted in local media as saying the state government viewed the move as necessary for “social harmony” even though it had to forgo an annual sum of RM2,544 of revenue from operating licences.

It became the fourth state under a PAS-led administration to stop issuing licences for gaming outlets, after Kelantan, Terengganu and Kedah.

Kedah’s 45 gaming shops were closed in 2023 after the state decided not to renew the licences of such premises, with local media reporting Chief Minister Sanusi Md Nor saying that the people would have to vote for BN or Pakatan Harapan (PH) to reopen these outlets.

Kelantan and Terengganu had banned these establishments in the states in 1990 and 2020 respectively.

Some political observers felt growing conservatism in the country was one of the factors that resulted in PAS being the biggest winner in Malaysia’s 2022 general election, winning 43 seats, the most held by a single party.

This was more than double the 18 seats it captured in the 2018 election.

The party repeated its stellar performance during the elections in six Malaysian states in August 2023, winning 117 of the 127 seats it contested, and extending its reach beyond its traditional stronghold of the Malay-belt states of Kelantan, Terengganu and Kedah. It also made inroads into states like Penang and Selangor.

Related:

ANALYST: YOUNGER NON MUSLIMS IN CERTAIN STATES NOT WILLING TO LIVE WITH RESTRICTIONS

The elderly Chinese communities in states such as Kelantan and Terengganu accept the fact that they are a minority and are willing to live with restrictions, as long as they're allowed to practise their faith and festivals behind closed doors, believes Professor of Asian Studies at University of Tasmania James Chin.

“But for the younger ones, what is very clear to me is that they're not willing to live with increasing restrictions. A lot of them claim it is about economic opportunities, but I suspect a bigger part of it is actually the social restrictions and the fear that things will actually get worse for the non-Muslim community,” he said.

Non-Muslims in both states who spoke to CNA generally felt there was nothing to be afraid of with PAS, although they hoped for fewer limitations.

Mdm Si Kaycee, 61, who runs a minimart in Kuala Terengganu’s Kampung Cina said it was unfortunate that various restrictions were placed on everyone in the state.

She said her two daughters have moved to Singapore and Klang Valley, where they are earning a better living.

“It’s unfair but we adapt, those who struggle to adapt are the younger generation … They don’t agree to live with these restrictions … I still see them but it’s a shame they were forced to move away from their hometown for a better life,” she said.

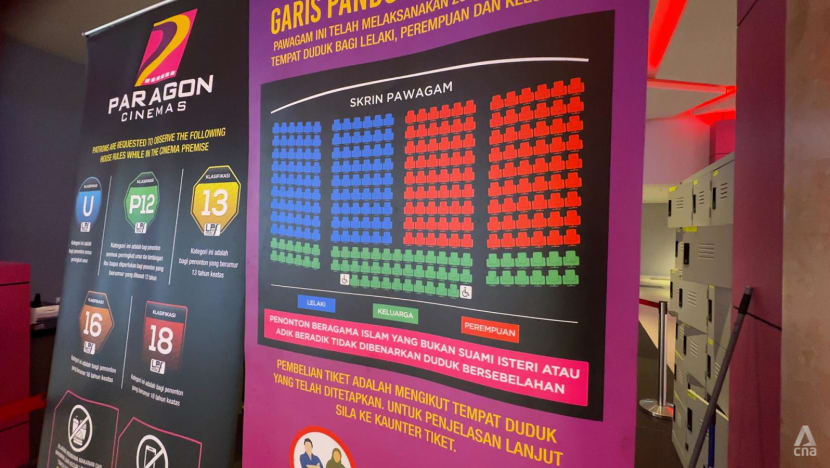

She said that there were certain regulations, such as gender-segregated cinemas and swimming pools, that were not enforced but still unnerving.

“When we go to cinemas in groups we would just sit together. It is unsettling that there's this law but we learn to live with it,” she said.

She, however, insisted that residents were not scared of PAS as they are not the Taliban, the fundamentalist group in Afghanistan.

Mdm Jennifer Ang, chairman of Terengganu Kopitiam and Restaurant associations, claimed that many non-Muslims found ways to gamble, including going to states such as Pahang to do so.

The owner of the T-Homemade Café - a kopitiam in Kampung Cina, Kuala Terengganu - said there were also those who did it illegally.

She hopes, however, that the state government does more to draw tourists by organising more programmes. A recent event was the Chap Goh Mei festival, a Chinese Valentine’s Day celebration, in the city.

“Malays and Indians were also celebrating it with us. But it was just one night in a long while. I hope we can do it at least once a month, to celebrate Chinese festivals. It should (organise more activities) to boost tourism … make it like Melaka’s Jonker Street,” she said, referring to the bustling Chinatown street in the southern state.

A Kelantanese antiques seller who wanted to be known only as Mr Bhavin, 73, said he wasn’t affected by the ban on gambling as he does not gamble, but has had to save watching movies for when he travels out of the state.

“It’s a shame they don’t have any cinemas here. They don’t allow busking and music too,” he said.

But moving away is out of question as his family and business are in the state. He said he is able to make a good living there.

“We hope PAS will reduce restrictions for non-Muslims, and only place prohibition on Muslims because the (Syariah) law should not apply to us,” he said.

REGULATIONS DEPEND ON WHAT LOCAL COMMUNITY WANTS: PAS INFO CHIEF

PAS information chief Ahmad Fadhli Shaari told CNA that certain regulations were drawn up because locals wanted them.

“It depends on the societies that have those sorts of values. If PAS becomes part of the government, it will look at the acceptance of the locals on these issues,” he said.

He said that when PAS was part of the Selangor government from 2008 to 2015, it did not seek to impose any conservative regulations.

Mr Ahmad Fadhli also said that there was a perception that PAS only focused on morality and religion. “Some of our statements on these issues are raised but when we speak on issues such as the economy, it would often be ignored," he said.

“It’s as if PAS only speaks about religious things or moral policing. PAS is more than that and Kelantan is the best testimony for that. In Kelantan, non-Muslims are not disturbed or (have a way of living) forced onto them."

PAS was part of the Pakatan Rakyat coalition with Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) and the Democratic Action Party (DAP) before the coalition was dissolved in 2015.

“In Kelantan, the community is different. If we are given the chance to govern Malaysia, it’s not as if we would make Kelantan the benchmark. The benchmark would be how comfortable the local community is with the situation.

“Nonetheless, there will be certain regulations that would have to be adhered to. Even the freedom of (dressing) is not absolute ... when Pakatan Harapan (PH) and Barisan Nasional (BN) are ruling, there are limitations as well.

“For example, can you wear shorts in parliament? You can’t. Can you wear a skirt? No. This means that certain limitations have been introduced. That is the duty of the government to evaluate,” he said.

Additional reporting by Amir Yusof