Political Islam: As insurgency drags on in Thailand’s Deep South, a new generation is swept up in the conflict

In the last of a five-part series on political Islam in Southeast Asia, CNA takes a deep dive into the long-running insurgency in Thailand’s Deep South and whether an end to the conflict may materialise under the civilian government of Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin. What are the wider implications for the region?

Police inspecting vehicles at a checkpoint in Yala, Thailand, part of the country's Deep South where a a separatist insurgency has killed more than 7,300 people since 2004. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

PATTANI, Thailand: On Mar 14, security forces surrounded a rural house in Thailand’s Pattani province, deep in the country’s restive southern border region.

Officers negotiated with two armed men who had holed themselves in. The men were suspected insurgents, linked to separatist movements pushing for the region’s independence from the Thai state.

The officers asked community leaders and Muslim religious leaders in the village - located in the Sai Buri district - to help persuade the two men to surrender and lay down their arms, Thai PBS World reported.

These negotiations sometimes take hours, and when they fail, there is usually only one outcome. The security forces moved in to flush the suspects out. They took fire and fired back.

Officers shot one suspect dead and asked the other to surrender, but he declined. The firefight resumed briefly, before officers moved in again. They found the second suspect dead as well.

A video of the incident from official sources, seen by CNA, showed operatives in bulletproof vests crouching behind pick-up trucks amid a constant rattle of flying bullets interspersed with a dramatic soundtrack.

On the same day, Facebook pages focused on developments in the southern border provinces posted about the men’s deaths and their funeral. They were described as “syahid”, which is Arabic for Muslim martyrs.

This incident was one of the latest in the decades-long insurgency in southern Thailand, which has killed more than 7,300 people since a renewed wave of violence erupted in 2004.

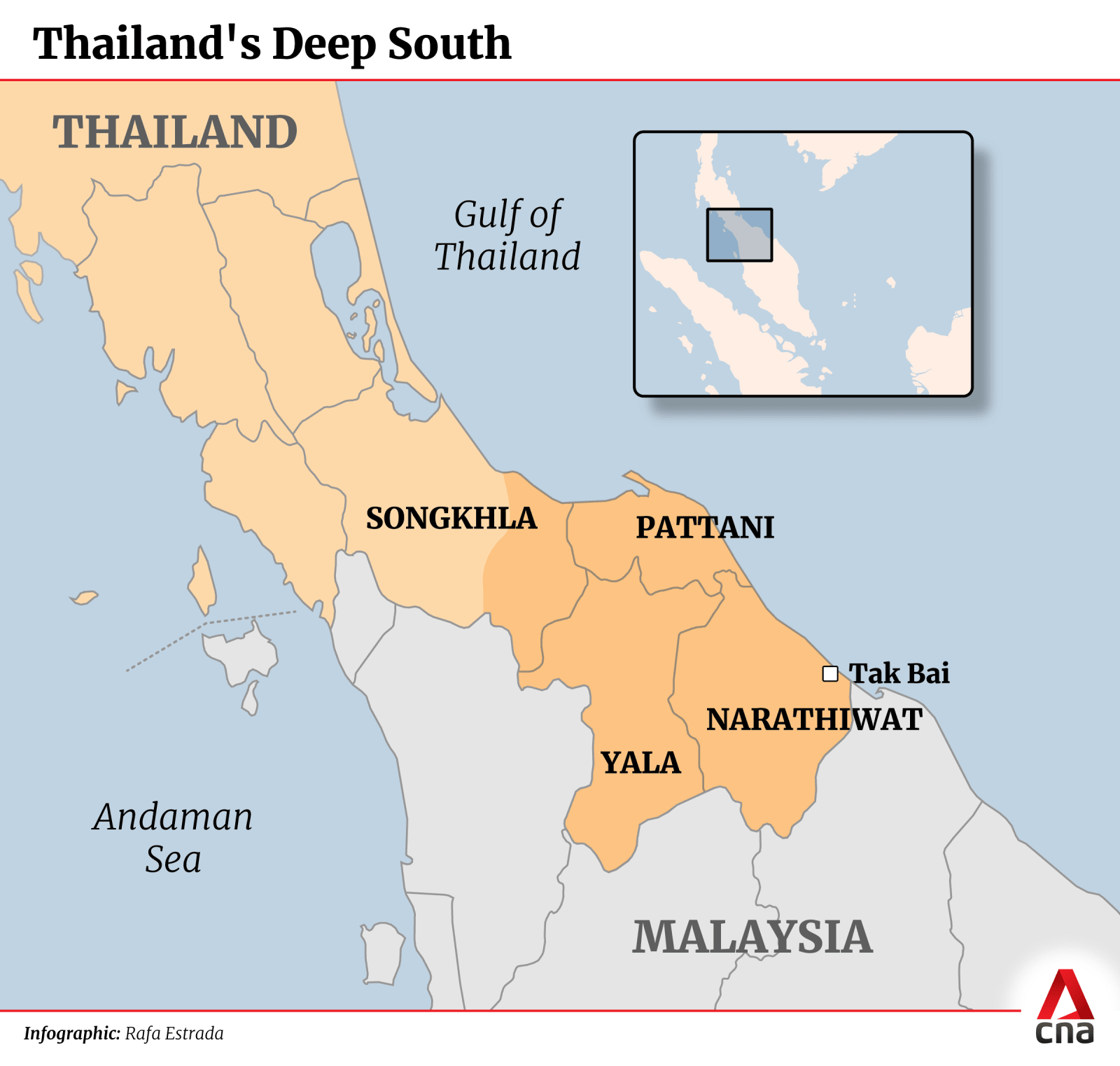

The conflict plays out in an area called the Deep South, referring to the southern border provinces of Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat and parts of Songkhla. These were part of an independent Malay sultanate named Patani before it was annexed by Thailand in 1909 under a treaty with Britain.

For decades since then, violence has flared on and off as armed rebel groups demanded independence for the ethnically Malay and predominantly Muslim region. Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) is currently the largest separatist group.

Independence remains BRN’s ultimate goal, but observers and former members said the group could be willing to accept some form of self-governance within the country, amid a realisation that the Thai state will never cede territory.

While the conflict primarily involves ethnicity and nationalism, the close link between ethnic and religious identity means it has taken on religious overtones.

Now in its 20th year since a renewed wave of violence that began in 2004, the conflict in Thailand’s Deep South is not the only hotspot in Southeast Asia against religious armed insurgencies.

One of the other places in the region where Islamic militants have resorted to violence is in the southern Philippines. Violence and conflict has plagued the region of Mindanao for decades as the government battled extremists and insurgents. The prolonged conflict has left the poverty incidence in the Mindanao region higher than the national average.

The Muslim separatist Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) started fighting for an independent Moro nation in 1968 and signed a peace agreement with the Philippine government in 2014, withdrawing their fight for independence in exchange for enhanced autonomy in a Muslim region called the Bangsamoro, according to Reuters.

And while MNLF has come under the government fold, smaller militant groups including the violent Abu Sayyaf have continued to fight the government and wage sporadic attacks.

In both the cases of Mindanao and Southern Thailand, Malaysia has facilitated peace talks in line with its own security interests, due to the conflicts' proximity to its borders. Ethnic conflicts can spill across borders, cause mass migration and complicate foreign relations.

Observers note that Malaysia has been able to accomplish more in Mindanao’s peace process because of several factors, including how the Philippine government is more open towards third-party involvement.

CNA has reached out to the office of Mr Zulkifli Zainal Abidin, Malaysia's chief facilitator in the Thai peace dialogue, for comment.

With ongoing talks on the table to resolve the issue in Thailand’s Deep South, how has the interplay between religion and politics affected the lives of people there, and is permanent peace possible?

MARTYRDOM

Both the Thai government and BRN, however, were keen to play down the role of religion in this conflict.

A former BRN member told CNA the group’s fight for independence is predominantly centred around the Malay identity, but includes religious Islamic elements to attract foreign support, especially from Arab nations.

A representative of the Thai military said the conflict was not a “religious” one, as he highlighted that people of different religions live peacefully with each other in multicultural Thailand.

However, Major-General Pramote Prom-In, deputy commander of the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) Region 4, warned against notions of martyrdom among insurgents. The 4th army covers the southern border provinces.

“We need to be careful about how these groups are going to children and telling them that if they do this, they will become martyrs and go to heaven,” he said through an interpreter at a media briefing for CNA.

“We need to be wary of this kind of mindset as it will make the peace process more difficult.”

On the other hand, a local activist who pools donations for family members of those slain by security forces said these cases were examples of extrajudicial killings.

Mr Zahari Abdul Wahab, 41, has recorded 73 such cases since 2020, when BRN announced a unilateral ceasefire as a goodwill gesture to let healthcare workers travel freely during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite appeals by local activists for the military to stand down and reciprocate BRN’s stance, the army at the time sent troops to hunt down BRN combatants staying in remote villages.

Mr Zahari said these suspected insurgents have never been convicted in a court of law, and they almost always die in the same circumstances as the incident in Sai Buri.

“On the surface, it feels like these people are not treated like human beings, so I feel sad. But as Muslims, they always pray that they get to be martyrs.” he told CNA.

“This is hard for me to understand as well. Their family members thank God that these men have entered martyrdom. But for us, we feel it’s unjust for them, so we criticise the government’s policies.”

A long road to lasting peace

Observers said incidents of violence have decreased since peace talks between Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) and the Thai state started in 2013. The talks have also yielded temporary ceasefires, but little else in the way of a lasting resolution.

At one of the most recent meetings hosted and mediated by Malaysia on Feb 7, 2024, the two sides agreed in-principle on an updated version of the Joint Comprehensive Plan Toward Peace (JCPP), a draft roadmap that includes reducing violence, public consultation and finding a political solution.

At the time, the parties also discussed a ceasefire from March to April, spanning the Muslim holy month of Ramadan and the Thai festival Songkran. There had been no updates since.

In a state visit to Thailand just days after, Malaysia Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim said his government is committed to helping Thailand solve the long-running insurgency issue. Malaysia shares a common land border with Thailand.

“We have to appeal to all forces both in Thailand, and in the south and even some in Malaysia, to understand and appreciate that peace must be paramount, of paramount consideration,” Mr Anwar said, according to the Associated Press.

The military general Mr Pramote Prom-In and the former BRN member - both of whom have direct knowledge of the latest negotiations - told CNA that a ceasefire has not been agreed, with both sides having different demands and expectations.

For example, BRN is asking the military to pull out of the three provinces, but the military wants a ceasefire first to see if incidents of violence can be dialled down, before implementing further measures to restore normalcy.

Mr Pramote, who is on the government’s negotiating team, said there are plans to open a “public space” for residents with political opinions. Civil society organisations and private firms have also been asked to support the dialogue.

Both sides are holding technical discussions and trying to reach a “compromise” on how to move forward under the JCPP, he said, calling the situation positive for future discussions.

The two parties will meet again from Apr 28 to Apr 30, he said, though he declined to provide specifics as both sides have agreed to speak publicly only in broad terms.

When pressed about plans for a ceasefire, Mr Pramote said this was “difficult” to achieve, as he alluded to how the BRN could take up arms indiscriminately, while security forces needed to follow the law.

Nevertheless, Mr Pramote revealed that government negotiators have a one- to three-year plan to restore normalcy in the region, depending on how quickly incidents of violence dwindle.

This would involve, in phases, lifting the emergency decree in more districts, letting insurgents turn themselves in without getting prosecuted, and eventually disbanding security forces while retraining them in other jobs, he said.

“But at each phase, we will face difficulties. It is the same everywhere in the world,” he added. “The most important thing is we must continue the dialogue and inform the public.”

COMPLEXITIES

In a way, the contrasting sentiments on these deaths highlight the complexity of the conflict and why it is so difficult to resolve, with clashing ideologies rooted in historical incidents of violence and discrimination.

Over the years, insurgents have carried out drive-by shootings and bombings targeting security forces or certain businesses, with these attacks sometimes taking place in crowded places and causing civilian casualties.

Patani Malays - who are predominantly Sunni Muslims - on the other hand accuse security forces of routine abuses. These include arbitrary and extended detentions without charge as well as extrajudicial killings in a region subjected to special laws that give forces extra powers and near-blanket immunity for their actions in the line of duty.

The special regulations are martial law, internal security act and emergency decree. The latter lets security forces detain suspects without charge for up to 30 days, and grants the government broad powers to censor the news.

Mr Pramote said the special laws are in place to maintain peace and restrict the movement of armed groups, and that despite their broad powers, security forces must follow protocol during every stage of investigations. Their actions must also comply with a law against torture and enforced disappearance, he said.

While the general acknowledged that the deaths of suspected insurgents during raids could be perceived as extrajudicial killings, he said authorities are responsible for enforcing the law when rebels carry out attacks.

“When security forces meet these armed groups, these groups are ready to die. They don’t want to negotiate and prefer to fight to their death,” he said. “We feel sad these things happen, but we cannot avoid it.”

An academic who has done in-depth research on human rights issues in the conflict said Islam is not just a religious or ethnic marker for Patani Malays, but also a “cognitive prism” they use to make sense of their everyday life and the conflict itself.

Dr Pakkamol Siriwat told CNA these freedom fighters command respect among locals, with the notion of "syahid" reflected in their everyday lived experiences, from funeral processions to public commemorations like donations.

The senior policy advisor at the International Organisation for the Least Developed Countries (OIPMA) said the state’s counterinsurgency measures have significantly helped Patani Malays maintain an ethos of “collective victimhood” in the conflict.

“The prolonged nature of targeted violence and military response characterised by the heavy-handed approach of the Thai government, including military and emergency decrees, has often been cited as exacerbating tensions and fostering cycles of violence,” she added.

“The emergence of youth support and a new generation of freedom fighters are in many ways a backlash to the counterinsurgency measures by the Thai state.”

Locals CNA spoke to seem to be divided on BRN’s use of violence in its campaign.

Some said the insurgency endangers even Patani Malays and their ability to go to work. Others said BRN’s actions compelled the state to give more recognition to their identity, by scrapping forced assimilation policies and allowing more equal opportunities in official jobs and education.

But they agree that the improvements need to go further, as they feel the military continues to stifle freedom of expression and association. Anyone suspected of supporting or promoting separatist movements could be surveilled or investigated for criminal offences, they said.

DISTRUST

For instance, a number of activists are being investigated by authorities after participating in a mass gathering organised by local non-governmental organisation Civil Society Assembly For Peace (CAP) in 2022 to promote Malay culture and commemorate Hari Raya.

CAP former leader Bung Aladi told CNA his organisation firmly disagrees with the use of violence to further the Patani Malay cause.

At the same time, the 42-year-old criticised peace talks for moving too slowly, as he hoped for the process to continue and pave the way to self-governance.

Under Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin, the new Thai civilian government has appointed National Security Council deputy secretary-general Chatchai Bangchuad as chief negotiator, the first time in nine years the role is held by a civilian.

But as far as peace talks go, Mr Aladi is under no illusions that the new government will act any differently.

“This new government was formed through a democratic process, but the truth is the military still holds a lot of power,” he said.

If Thai authorities are sincere about the peace dialogue, they should try to minimise prosecutions meant to chill expression of opinion, said Dr Rungrawee Chalermsripinyorat, a lecturer at the Institute for Peace Studies in Prince of Songkla University’s Hat Yai campus.

“But in reality, the military is not always following other agencies. The National Security Council might be leading the peace dialogue, but then on the ground is ISOC,” she said.

“The government still cannot really ensure that whatever the peace dialogue panel says will really happen on the ground,” Dr Rungrawee said, adding that this needs to be addressed before public consultation starts.

“Because otherwise, the BRN and also people who will take part in the process will not trust the process.”

SELF-GOVERNANCE

The former BRN member, who spent 20 years in its military wing and is considered a third-generation leader, told CNA that the group will reject a ceasefire as long as the dialogue is held under the ambit of the Thai constitution, which counts separatism as a serious violation.

“My opinion is that our fighters today still firmly stand for full independence,” said the 53-year-old man, who only wanted to be known as Abdulloh because he feared reprisal from other members for speaking to the media.

“But if the negotiations in Malaysia lead to autonomy, I think our people will accept it in the spirit of compromise.”

Mr Abdulloh, who said he personally knows most of the people on BRN’s current negotiating team, said the group is asking the military to pull back its troops from the three provinces, and grant immunity to some of BRN’s wanted members so they can take part in the peace process.

Instead, government negotiators are asking BRN to agree to a ceasefire and stop conducting attacks, he said.

“The talks don’t go beyond the constitution, which states that land cannot be divided. So, how can the talks lead to a ceasefire?” he asked.

Mr Abdulloh suggested that BRN could accept two forms of self-governance within the Thai state: Full autonomy with open elections, or partial autonomy in less security-sensitive areas like economic development and education, but with elections reserved for BRN members.

“The conflict will never end if there is no independence,” he added. “This is the big picture, but I am confident that if our representatives are offered autonomy, they will accept it.”

PUBLIC PRESSURE

Mr Pramote said challenges with the peace process include public fears that the government could lose out to separatist groups and compromise national interests.

Dr Asama Mungkornchai, a political science lecturer at Prince of Songkla University’s Pattani campus, said BRN’s demands for self-governance could be described as decentralisation, a governance concept she said is “nothing new”.

“But the main problem is that the Thai state and most Thai people think they will lose Thai territory if they give self-determination here,” she told CNA.

“We have implanted the Thai nationalist concept in the Thai people’s psyche since a long time ago.”

Dr Asama believes Islamophobia also plays a role in stoking this sentiment, citing hate speech against Muslims on social media that she thinks are from actual Thai people and not information operations.

Ms Busyamas Isadun, a Buddhist, grew up in Narathiwat before moving to Yala, where she has lived for the past 55 years.

The 57-year-old said the conflict has not made her fear Muslims or Islam as a religion, believing that the rebels do not hate non-Muslims but are fighting for what they feel are their rights.

“We know that we can speak normally with members of these groups. Non-Muslim religious groups have actually reached out to the BRN a few times to ask how their safety can be guaranteed,” she said.

Ms Busyamas recounted how after separatist attacks started creeping into the southern cities, non-Muslim residents started moving out in droves to places like Hat Yai, fearing they could be targets.

She estimated that there used to be 500,000 non-Muslims living in the Deep South, compared to the 80,000 now. Over the years, ethnic Thai Buddhists - including civilians like teachers - have been targeted in retaliatory attacks.

The current situation has left Ms Busyamas feeling “uncomfortable”, especially as she knows non-Muslims living in the suburbs could still be vulnerable to retaliatory attacks by armed groups after the recent raid in Sai Buri.

“We know that in the next few days there will definitely be payback. Targets could be Buddhists who are working as police officers or rangers,” she said.

Ultimately, Ms Busyamas said she does not place any hope in the peace dialogue as previous iterations have failed to yield anything substantial, with the public kept in the dark about whether the BRN’s demands were accepted or rejected.

“Don’t forget that the people sent (by the state) to the peace dialogue have no power to make any decision. When they return, they must report to the central government,” she said.

“Whether the central government sees the peace dialogue as important or not, we don’t know.”

POLITICAL WILL

Dr Rungrawee from the Institute of Peace Studies said she does not see political will from the current government to resolve the conflict.

The Thai prime minister’s recent visit to the Deep South near the end of February focused more on issues like economic development and tourism, she said.

“But we cannot really have full economic development in the area if there is no sustained peace,” she added.

“We still do not really see strong leadership from the current government led by Srettha Thavisin and the Pheu Thai party. The government has not really shown any clear stand on the peace talks.”

Dr Pakkamol, the human rights researcher, said political instability and changing governments in Thailand could lead to shifts in policies and priorities regarding the conflict, affecting the continuity of and commitment to peace talks.

For instance, the BRN put peace talks on hold ahead of the general election on May 14 last year, as the group wanted the political situation to be more stable before the process could continue.

The election season saw military reform become a major topic of conversation, particularly among youth, as Move Forward Party leader Pita Limjaroenrat pledged to “demilitarise” the country.

After Move Forward emerged as the surprise winner of the election, in a resounding rejection of more than a decade of rule by the military and a military-backed government, Mr Pita was asked if his party would allow the Deep South to break away from Thailand.

He replied that the problem was rooted in the livelihoods of local people, a response that was criticised by his progressive voters on social media as not being brave enough, noted a Benar News commentary by Deep South security analyst Don Pathan.

Conservative opponents and a military-appointed upper house Senate then twice rejected Mr Pita’s bid to get voted by parliament as prime minister, leading to a split in Move Forward’s coalition with election runners-up Pheu Thai.

Pheu Thai went on to form the government with military-allied parties and senators, while Move Forward ended up in the opposition.

In March, the Election Commission of Thailand sought to dissolve Move Forward over concerns that its reformist election campaign to change the law against insulting the monarchy undermines the country’s governance.

The commission’s decision followed a Constitutional Court ruling in January that the party had violated Thailand’s constitution with its plans to change the country’s lèse-majesté laws, which forbids offence or defamation against a ruling head of state.

Dr Rungrawee said political leaders need to show strong support for the peace process to create a conducive atmosphere for talks to progress.

“It would need the government to say whether they are willing to consider political autonomy,” she said.

“If there is no will to give substantive power to the region, it is going to be hard for the peace dialogue to make any meaningful agreement.”

Dr Pakkamol said confidence-building measures, such as reducing military presence and addressing human rights abuses, could help build the trust necessary for meaningful negotiations.

“However, exploring options for greater autonomy or decentralisation that respect cultural and religious identifications and addressing the social injustices faced by the Patani Malay community could be the key to resolving the conflict,” she said.

“In this matter, I believe that neutral international mediators could help facilitate dialogue, ensure the enforcement of agreements, and monitor the implementation of peace accords to ensure progressively the achievement of any form of sustainable peace in the region.”