Chinese schools in Malaysia attracting more children of other races, amid allegations of sowing disunity

While opponents of vernacular schools say that they should be abolished to preserve national unity, the enrolment of Malay students especially in Chinese schools has been rising over the years.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

KUALA LUMPUR: Restaurant operator Siti Sarah Abdul Rashid began enrolling both of her children aged seven and eight in a Chinese primary school this year.

The 36-year-old of Malay ethnicity and her American husband George Bourdelais, did so despite both of them not having any background in Mandarin - the medium of instruction used in such schools.

The reason for sending their two children to the SJK(C) Jalan Davidson school, Mdm Siti said, was for them to learn another language proficiently in order to enhance their career prospects.

“(So many people in the) world speak Chinese and many companies nowadays require Mandarin-speaking candidates,” she said, adding that Chinese schools also place an emphasis on students’ discipline.

To ensure their children keep pace at school, the couple are sending them for extra classes to brush up on their Mandarin.

Mdm Siti said she was told by a fellow parent that the number of Malay students who had enrolled in primary one at the school had increased from two in 2023 to eight this year.

It is part of a wider trend across Malaysia. Earlier in March, it was widely reported that all 20 primary one students enrolled at the Si Chin Chinese School located in Bahau, Negeri Sembilan were Malays.

According to activist Arun Doraisamy of the Malaysia Centre of Vernacular School Excellence, about 20 per cent of students in all Chinese primary schools across the country in 2024 are non-Chinese, up from about 12 per cent in 2010.

But these Chinese schools - which are attracting more non-Chinese students - have also drawn brickbats from certain quarters who argue that they are a roadblock to Malaysia’s national unity and want them shut.

It is a debate that has raged for years and resurfaced following a recent court ruling that vernacular schools in the country are not unconstitutional.

Surprisingly for Mdm Siti and her husband, the opposition to enrol their two children came from certain quarters in the school itself, who dissuaded them from doing so as the couple and their children did not know Mandarin.

“I questioned myself if I was doing the right thing, but my friend told me not to be dissuaded and that it would take some time before the children became good at it,” she said.

SCHOOLING SYSTEM IN MALAYSIA

The national school systems in primary education are divided into national and vernacular - Chinese and Tamil medium - schools. These schools have the same syllabus as national schools, barring the language subjects.

Malay is used as the medium of instruction in the national primary schools while in the vernacular schools, Mandarin and Tamil are respectively used as the mediums of instruction and communication.

Data from the Ministry of Education in 2020 showed that there were 7,780 primary schools across Malaysia then.

Of these, 5,875 were national schools, 1,299 were Chinese schools, 527 were Tamil schools and the remaining were special education schools, special model schools as well as government-aided religious schools.

According to the latest data from Mr Doraisamy, there are 1,831 vernacular primary schools in Malaysia this year – 1,301 Chinese and 530 Tamil.

Once students have completed their primary education, they can enrol in national secondary schools or independent schools.

While there are no Tamil secondary schools in Malaysia, there are 82 Chinese government secondary schools (also known as SMJK) and 63 independent Chinese high schools in the country.

As of 2021, there were altogether 2,444 secondary schools in Malaysia, including the SMJKs.

The SMJKs were once Chinese-medium schools but opted to use the Malay language and the national syllabus for government aid. At the same time, these schools allocate more time for Mandarin lessons for their students.

The independent Chinese high schools, on the other hand, are not government funded and use the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC) syllabus, which is not recognised by the Malaysian government.

In February, the Federal Court ruled that vernacular schools are not unconstitutional, after a challenge in court that was instituted by several groups that had sought to declare that the use of Chinese and Tamil languages as the medium of instruction in such schools went against the Federal Constitution.

They included the Islamic Education Development Council (Mappim), the Coalition of National Writers' Association (Gapena), Majlis Ulama Ikatan Muslimin (Isma) and Ikatan Guru-Guru Muslim Malaysia (i-Guru).

Mr Doraisamy told CNA that the narrative that these vernacular schools cause disunity was one usually brought up by special interests groups that promote “Ketuanan Melayu” - or Malay supremacy - as well as the Islamic agenda.

“Vernacular schools are an easy punching bag for these groups who are big proponents of assimilation and not integration,” he said, adding that these groups regularly harped on issues that are related to race and religion.

According to the latest population census in 2020, Malaysia is made up of 69.4 per cent Bumiputera (Malays and other indigenous groups); 23.2 per cent Chinese; 6.7 per cent Indian and 0.7 per cent other races.

Lawyer Wong Kong Fatt - who represents the United Chinese School Committees’ Association of Malaysia (Dong Zong) and the United Chinese School Teachers' Association (Jiao Zong) organisations - told CNA that the use, preservation and sustenance of the other vernacular languages in Malaysia’s education system should not be prejudiced against.

At the same time, Mr Wong acknowledged that the national and official language of the country is Malay.

“Since the use of Chinese and Tamil languages are not prohibited in the vernacular schools before, during and after the Federal Constitution, why is this issue brought up now?” he told CNA.

Mr Wong added that while minorities like himself identify as Malaysians, they could not deny their ethnicities.

“Even if I were to convert to Islam, I am still Chinese. I can't say that I am Malay. If we don’t use our language, it will be lost.

"At the same time, we recognise that we are Malaysians and respect the country and the national language,” he said, adding that vernacular schools should not neglect the teaching of the Malay language.

When contacted, an analyst said that such issues are brought up ever so often as political mileage - both by those who oppose and support these schools.

“The perception is that those who attend vernacular schools cannot integrate with the whole population as they are using their mother tongue and are only within their own community,” said Nusantara Academy for Strategic Research senior fellow Azmi Hassan.

“But we also have to realise that even national schools are becoming like vernacular schools in the sense that it is mainly made up of one race.”

RACIAL ISSUES AT THE FORE, AGAIN

Just last month, Professor Emeritus Teo Kok Seong - who is also a fellow with the National Council of Professors - claimed that vernacular schools in Malaysia are obstacles to national unity as the Chinese looked down on the Malays.

He also claimed that 95 per cent of Chinese students are sent to vernacular schools and that they refuse to integrate with the Malays.

Following multiple police reports lodged against him, Prof Teo was investigated for his statements under Section 505 of the Penal Code and Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998.

Many others have since waded into the debate, including the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) youth chief Dr Akmal Saleh who claimed that racial tensions in Malaysia stemmed from segregation at schools.

“It is time for Malaysia to put an end to this segregation and divide.

“There is no shortcut to achieve unity. It is a long, winding and challenging road, but it begins with a single step,” he was reported as saying by Free Malaysia Today, adding that there should be a comprehensive assessment of the syllabus taught at vernacular schools.

Separately, the Democratic Action Party vice-chairman Teresa Kok said that Prof Teo’s assertion was not only untrue, but also mischievous.

“Such statements only serve to perpetuate stereotypes and deepen rifts in our multicultural society.

“It is important to recognise that the vast majority of Chinese-educated individuals do not harbour such sentiments and actively contribute to a harmonious society,” she said in a statement on Mar 6.

INCREASE IN POPULARITY OF CHINESE VERNACULAR SCHOOL AMONG OTHER ETHNICITIES

Educationist Prof Tajuddin Rasdi of UCSI University denied suggestions that vernacular schools hinders national unity in the country, pointing to the increase in the number of Malay students in Chinese schools over the years.

“Why is it that the number of Malays have increased in the vernacular schools? There are even vernacular schools where Malays outnumber the Chinese,” he said in a video in response to Prof Teo that was posted on Mar 12 on the website of Aliran - a reform movement based in Penang.

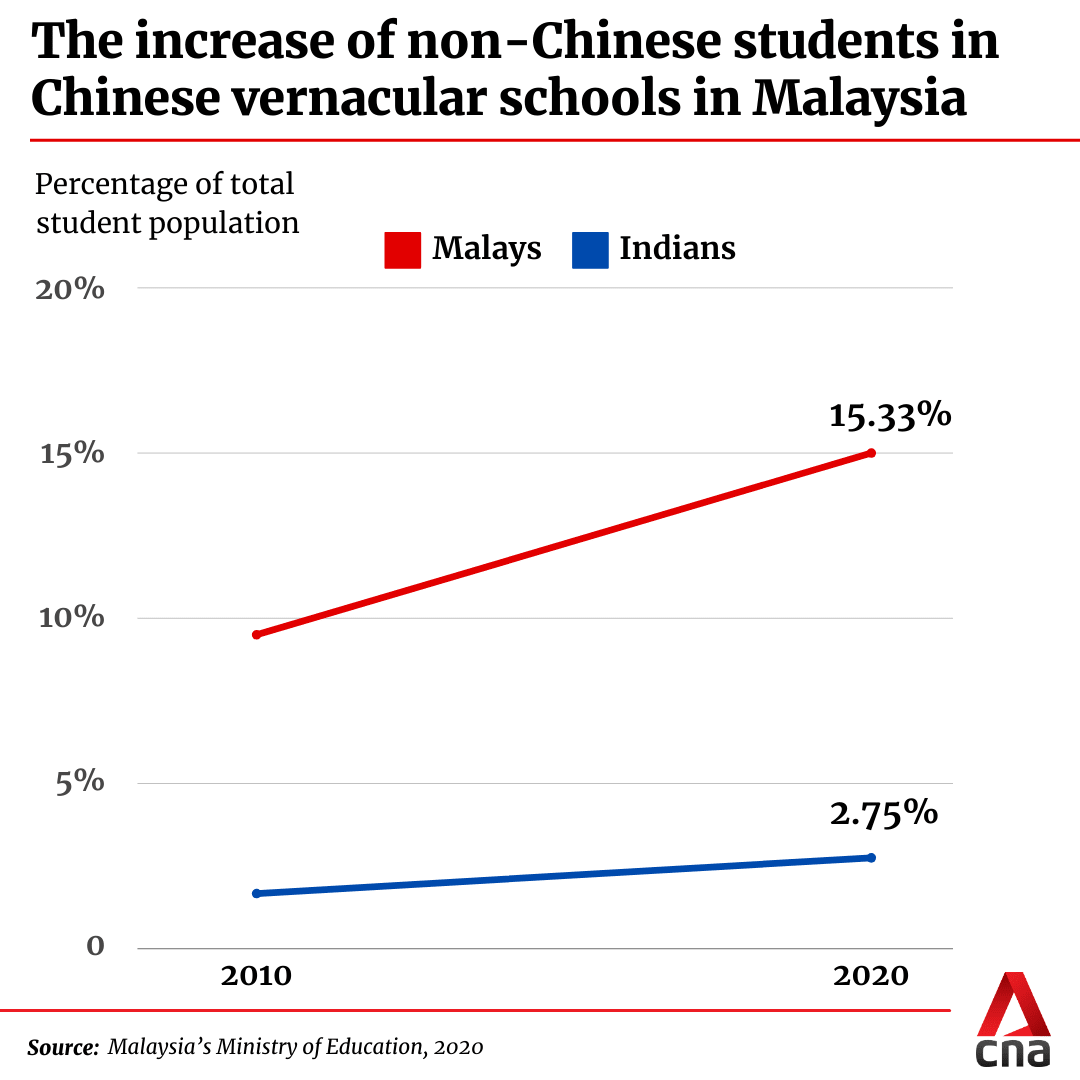

In Nov 2020, the then-Education Minister Mohd Radzi Md Jidin told Parliament that Malays comprised 15.33 per cent of the total student population in Chinese primary schools in 2020, up from 9.5 per cent in 2010.

At the same time, the number of Indian students in Chinese primary schools also rose from 1.67 per cent in 2010 to 2.75 per cent in 2020.

Mr Radzi also shared that the enrolment of both Chinese and Indian students in national primary schools had declined in the 10 years: The number of Chinese students declined from 1.17 per cent in 2010 to 0.73 per cent in 2020 while those of Indian students dropped from 3.15 per cent to 2.63 per cent.

Mr Doraisamy, the activist, does not believe that children studying at vernacular schools were the root of racial disunity in Malaysia.

“Most students will converge in the secondary schools. To suggest that vernacular schools cause disunity doesn’t make sense,” he said.

Mr Doraisamy’s opinion appears to be supported by a survey by the UCSI Poll Research Centre in March, which found that 70 per cent of the 1,010 participants polled agreed that vernacular schools do not hinder national unity.

Of the 1,010 Malaysian respondents, 407 were Chinese, 279 were Malay, 204 were Indian and 120 were Kadazan or Iban.

Some 65 per cent of those polled said vernacular schools should not be abolished in Malaysia while 16 per cent agreed that they should be closed and the remaining 19 per cent were unsure.

“This survey shows that vernacular schools are still relevant. Two in three respondents with children below the age of six would want to send their children to Chinese primary schools,” the pollster said in a release on Mar 24.

Even Malaysia’s National Unity Minister Aaron Ago Dagang waded into the issue, saying that vernacular schools provide a platform for students from diverse backgrounds to interact and understand each other.

"Last year, the ministry initiated the social deficit discourse, featuring experts in the field. The findings indicated that vernacular schools should no longer be perceived as sources of division among ethnicities but should function as platforms for managing social harmony, similar to the role of national schools," he said in a statement on Mar 11.

VERNACULAR SCHOOLS IMPORTANT

For many in the Indian and Chinese communities, vernacular schools are important in fostering a connection to their heritage and cultural identity. Beyond that, there is the perception that education standards at national schools have dropped, prompting parents to find an alternative.

Mrs Darshini Ganeson, 32, and her husband decided to send their seven-year-old son to a Tamil school in Rawang, Selangor because they want him to be proficient in his mother tongue.

Mrs Ganeson - who runs a delivery business - said that while she speaks Tamil with her two children at home, there was nothing like mastering the language by learning it in school.

She said that her son could have learned Tamil in a national school, but felt that the lessons would not have been as comprehensive.

“It is also my duty to support the vernacular school, otherwise there is a chance it could be demolished,” said Mrs Ganeson, who also attended a Tamil school.

She added that her son’s school taught Mathematics and Science in English - an option that is not available at every national school.

Acknowledging that her two children - which includes a three-year-old girl - will eventually have to study in a national secondary school eventually, Mrs Ganeson felt that they would have been proficient in Tamil by then.

“The main thing is for (them) to grasp the basics and (they) won’t forget it,” she said, adding that it was important for her children to know how to speak English and Malay as well so that they could survive in Malaysia.

For one parent who wanted to be identified only as Mr Heng, the decision to send his son to a Chinese school was not an easy one.

The 41-year-old told CNA that he never had any issues when he studied in a national school but believes that “times have changed” and that the standard of education there has dropped.

“If I could afford it, I would have loved to send my son to an international school but the fees are just too prohibitive. You could even study in university for the fees that you must pay,” said Mr Heng, who is from Melaka but now resides in Kuala Lumpur.

In the end, he and his wife decided to enrol their seven-year-old son in a Chinese school this year.

“It wasn’t an easy decision as neither my wife nor I went to a Chinese-medium school but it seemed to be the next best option. I would have wanted him to study in a multiracial environment like how I did, but there are many things to worry about in a national school,” he said.

BETTER STANDARDS IN CHINESE SCHOOLS, PARENTS SAY

The Chairman of the Parent Action Group for Education Malaysia (PAGE) Noor Azimah Abdul Rahim told CNA there was a perception among parents that teachers in Chinese schools were very dedicated to their duties.

“National schools have declined so much, and they will have to raise their standards if parents were to be confident in them and there can be a natural progression where they were the preferred choice of schools,” she said, adding that the discipline in Chinese schools was also considered to be better.

Mr Bourdelais - who along with his wife Mdm Siti - sends their two children to a Chinese school noted the stark difference in the conditions of the national schools and Chinese schools, calling the latter much “better” and “friendlier”.

“A friend who sent their children to a Chinese school said that it is all about discipline. I want my children to be focused on their schoolwork. I grew up in an environment where no one pushed me during my school years,” he said.

Separately, Mdm Fadzreena Noradreen Roslan - who enrolled her daughter in a Chinese kindergarten before sending her to a Chinese vernacular school - said that her child’s institution has a supportive Parent Teacher Association (PTA) who also contribute in terms of money and involvement in school activities.

Of the 40-plus students in her daughter’s class, about 10 are Malay.

The 38-year-old said that the school has facilities such as digital blackboards and large televisions as well as a hall where they can hold their own events, adding that students can choose from a wide range of activities, including a robotics class among others.

“If you want your kid to know a third language, they need to be surrounded by those who speak it. Mandarin is no longer an advantage but a requirement,” she said, adding that she also sends her daughter to Islamic classes during the weekend to make up for the lack of such classes in Chinese schools.

Social media influencer Mr Fab posted a video on TikTok on Mar 21 saying that there were several reasons why Chinese schools were becoming a big draw for parents.

Mr Fab posts content on education, with his video on Chinese schools racking up more than 110,000 views.

This included facilities provided in the Chinese schools such as smart televisions, smartboards, projectors, and fully-equipped gymnasiums as well as sports facilities.

Mr Fab - who taught English in a Chinese school for 10 years - also said that the Chinese schools organised many projects such as concerts, food sales and competitions for the benefit of the students.

“The students will be exposed to many things and skills that are not learned in class but are obtained when they organise (and participate in) these events,” he said, adding that there was also an emphasis on co-curricular activities aside from academic performance.

“I was born and raised in a very religious environment but the school really opened my mind to look at the world from a wider perspective,” he added.

Mr Heng - who sends his son to a Chinese school - has some choice words for those intent on abolishing the current system.

“You say that we should have one stream for schools. If you want that, then you shouldn’t be fighting for any one specific race or religion. Maybe it’s time that your parties and groups are also abolished for the sake of unity,” he said.