Myanmar refugees in Malaysia struggle to get a place in school, find limited opportunities

Thousands of Myanmar students have fled to neighbouring countries to pursue their studies since the military coup ended the nation’s short-lived democracy.

Ms Lian San Ching, a 22-year-old ethnic Chin who fled Myanmar for Malaysia two months ago, attends a class in Kuala Lumpur.

KUALA LUMPUR: Ms Lian San Ching, a 22-year-old ethnic Chin who fled Myanmar for Malaysia two months ago, is thankful to be able to resume her studies.

“I couldn’t find a job because I couldn’t speak English,” she said. “Although I passed my 10th grade back in Myanmar, I couldn’t speak basic English and couldn’t even support myself for my own survival.”

“I am hardworking, I want to continue my studies because if I can speak English, I can fit in better anywhere.”

Her principal Bella Cing Kop Khan, who heads the community learning centre at the Alliance of Chin Refugees (ACR) in Kuala Lumpur, was impressed by her drive and accepted her as a student in the centre.

Her fellow classmates are six years younger than her, but Ms Lian San Ching said she does not mind – she is luckier than many fellow refugees still struggling to find a place in schools.

The limited slots for education among the Myanmar migrants are often prioritised for younger children, leaving young adult students in the lurch.

LACK OF EDUCATION

Thousands of Myanmar students have fled to neighbouring countries to pursue their studies, in the two years since a military coup ended the nation’s short-lived democracy.

The army seized power from the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi in February 2021 and suppressed opposition to the takeover.

Many civilians, including students who joined street protests, were killed or arrested. Attacks on schools, teachers and students due to the conflict have left many too scared to return to classrooms.

Aid agency Save the Children said in June last year that half of Myanmar's children are now missing out on formal education, with enrolment dropping by up to 80 per cent in parts of the country since the unrest.

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns also disrupted school terms.

As a result, those who have fled to a new country are easily a few years behind their peers in education level.

“They feel they are too old; they don’t know English like others,” said Ms Bella Cing Kop Khan. “Because of all those weaknesses, they are afraid to go back to school but some are willing to try.”

MANY STUDENTS, FEW VACANCIES

Many refugee students eager to head back to school in Malaysia are finding limited opportunities and a dwindling number of vacancies in educational institutions.

“There are too many (refugees) already. The parents brought three, four kids along and unfortunately, because of a lack of space, (we are) fully occupied and they can't enrol anymore. I feel so bad for them,” said Ms Bella Cing Kop Khan.

Schools for ethnic Rohingyas, run by non-governmental organisations, are also facing the same issue.

With about 50,000 to 60,000 school-age Rohingya refugees vying for school places, there are more applications than availability.

Mr Mohd Azmi Abdul Hamid, president of the Malaysia Consultative Council of Islamic Organisations, said that while Rohingya students are bright and have outstanding learning capabilities, many schools are understaffed and poorly funded.

“It's remarkable, their absorption rate, their ability to learn is beyond imagination, they catch up very well,” he said. “They should be assets, not liabilities for us.”

“Education should be free for all school-going kids regardless they are stateless or refugees,” he added.

INFLUX OF REFUGEES

The reopening of Malaysia’s borders since April last year has seen a surge in refugees from Myanmar. Apart from a lack of education opportunities, they are also struggling with documentation and work.

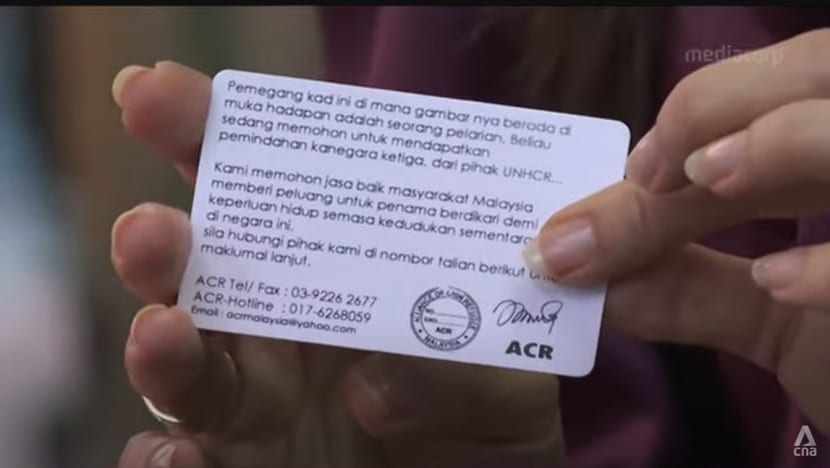

As many fleeing Myanmar nationals have no travel document, community centres in Malaysia have been tending to thousands of these new arrivals, issuing them cards printed with their identities.

However, the cards are not official documentation and are not recognised by authorities. They do not allow these refugees to legally work, study or seek medical help in government hospitals.

They merely identify card owners as refugees and contain wordings appealing to the community to help them eke out a living while they temporarily reside in Malaysia, and until they are resettled in a third country.

There are currently more than 180,000 refugees in Malaysia registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Of this, more than 80 per cent are from Myanmar, with children below 18 years old numbering about 50,000, according to the UN Refugee Agency.

Malaysian authorities have been conducting raids to weed out illegal migrants.

With Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim aiming to bring in half a million foreign workers to fuel the nation’s economic recovery, many NGOs have urged the government to help educate and train the refugee community so that they can be absorbed into the country's workforce.

However, Home Minister Saiful Nasution said there are no plans to change the laws regarding the status of the refugees at the moment.

“As of today, it remains status quo because there are other priorities to accept the refugees to work,” said Mr Saiful. “(But) Definitely that is one of the top topics that we will need to look into.”

Read this story in Bahasa Melayu here.