Should religious leaders reveal political leanings or join protests? Yes, say most respondents polled in Malaysia, Indonesia

The survey by the Pew Research Centre involving some 13,000 respondents in six Asian countries also found that about one in two Malaysians and Indonesians believe religious leaders should join politics.

File photo of Muslims waiting to pray at the Malaysia National Mosque in Kuala Lumpur on Apr 22, 2023. (Photo: AP/Vincent Thian)

JOHOR BAHRU: Around 6 in 10 respondents polled in Malaysia and Indonesia say religious leaders should talk publicly about the political parties or politicians they support, with about half even saying they should enter politics, a survey has found.

Also, more than half of the respondents in Malaysia and Indonesia believe religious leaders should take part in political protests, slightly more than the 50 per cent of those polled in Cambodia and eclipsing the 18 to 29 per cent of respondents in Singapore, Sri Lanka and Thailand.

These key trends emerge in the Pew Research Centre study released on Tuesday (Sep 12) which surveyed 13,122 adult respondents across six Asian countries between June and September 2022.

The countries are Thailand, Cambodia and Sri Lanka, where Buddhism is the official religion, Malaysia and Indonesia where most of the population are Muslims, as well as Singapore which has no religious majority.

The survey by the American think-tank also touched on a wide range of areas, including how respondents view the importance of religion to national identity, their preference in basing national laws on religious teachings, as well as their views on religious diversity.

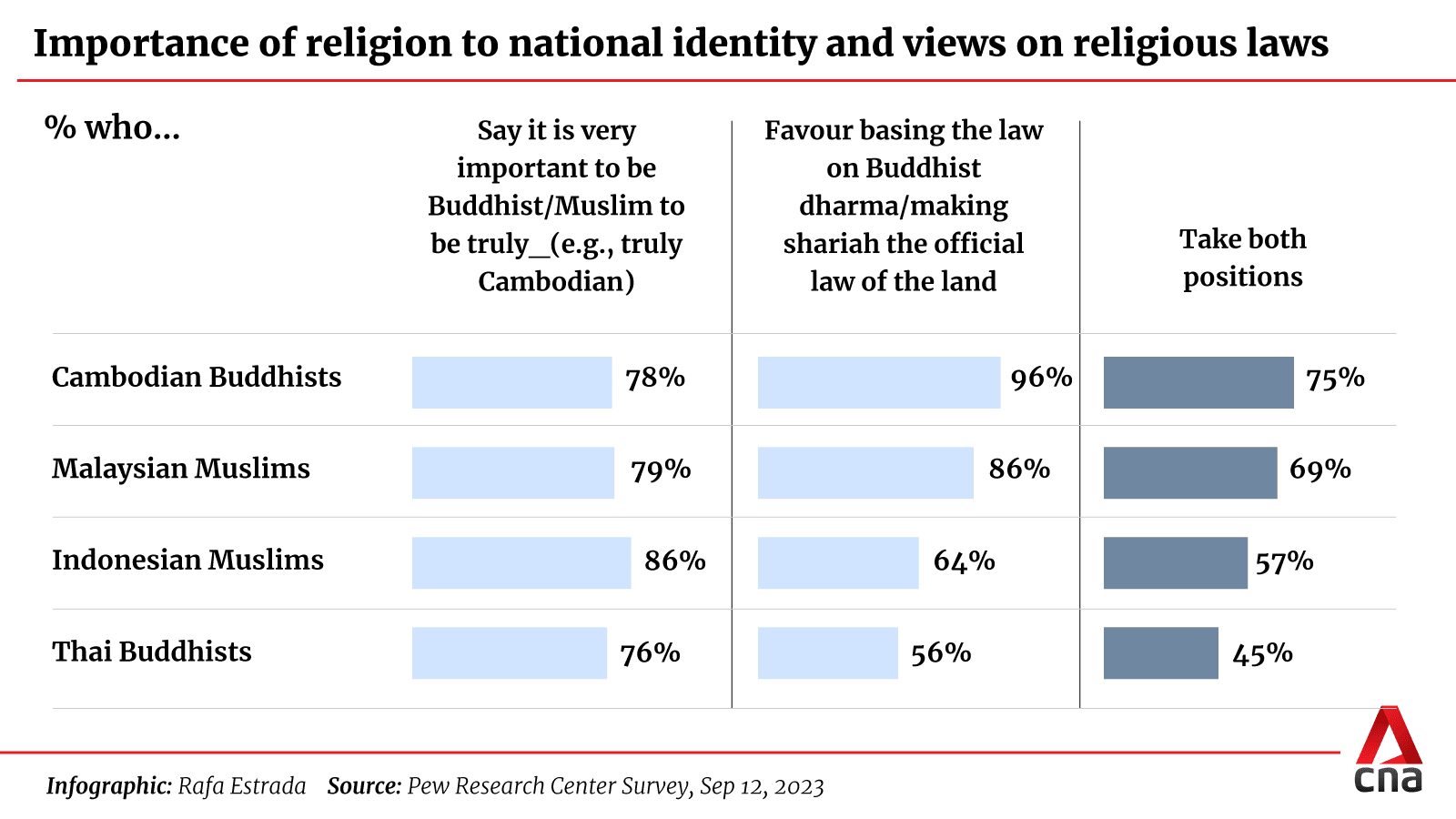

For instance, the survey found that 86 per cent of Muslim respondents in Indonesia say it is “very important” to be a Muslim to be truly Indonesian, which is closely followed by 79 per cent of Muslim respondents in Malaysia who also equate the religion to national identity.

One of the lead researchers on the study Jonathan Evans told CNA that several questions in the survey seek to understand how people think religion and politics “should or should not mix”.

“Since there are so many ways religious leaders could be involved in politics, we decided to ask a few questions to gain a higher degree of nuance than could be achieved by simply asking ‘should religious leaders be involved in politics?’,” said Mr Evans.

“Overall, Muslims in Indonesia and Malaysia tend to be more likely than other Muslims in the region to say religious leaders should be involved in politics.”

PREFERENCE FOR NATIONAL LAWS TO BE BASED ON RELIGIOUS TEACHINGS

While the survey also includes Sri Lanka, CNA focused on findings from the five Southeast Asian countries that are geographically closer and whose religious dynamics are closely intertwined.

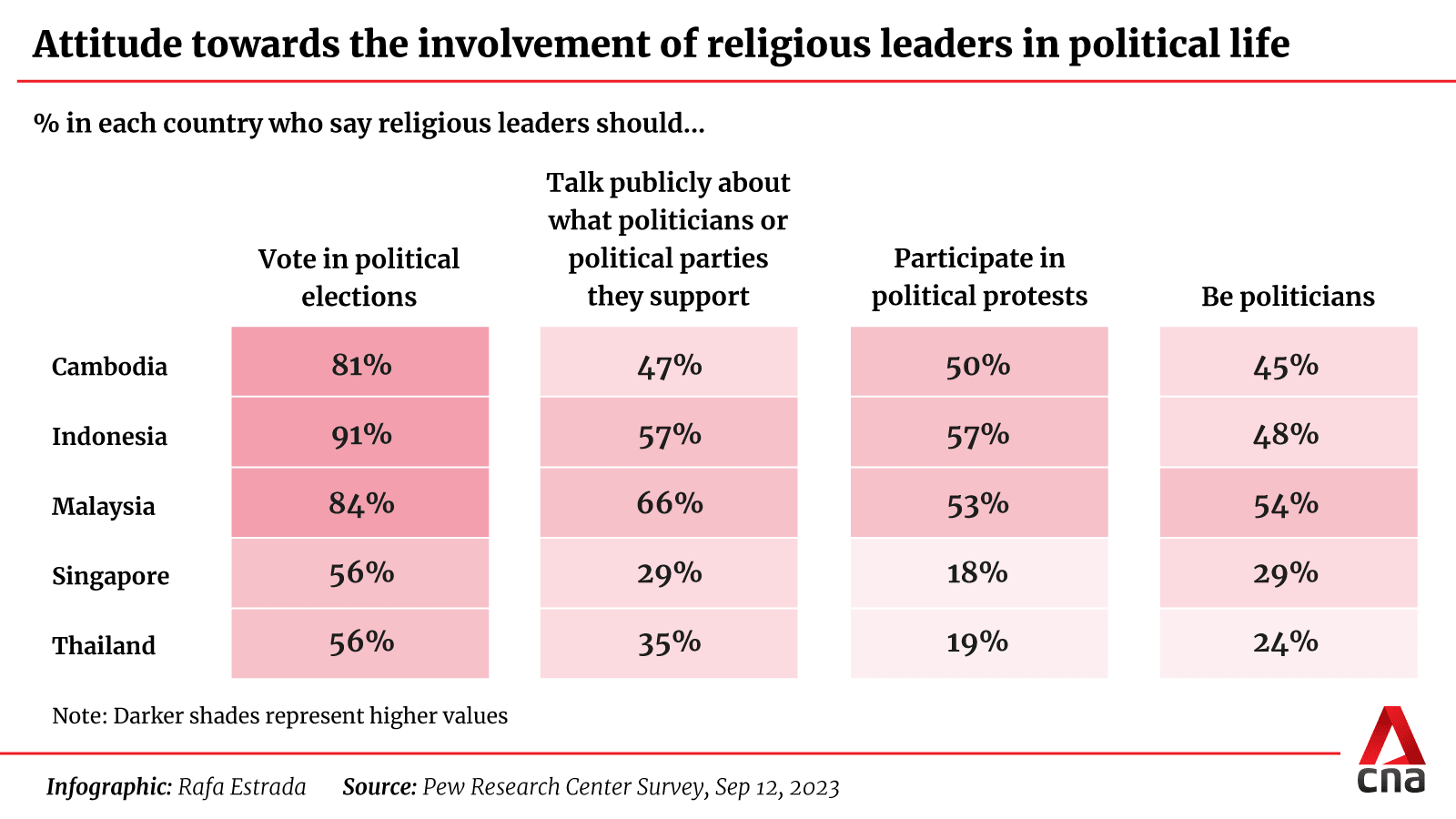

More than half of respondents across the five countries believe that religious leaders should vote in political elections.

For instance, 91 per cent of Indonesians, 84 per cent of Malaysians and 81 per cent of Cambodians say religious leaders should cast ballots at the polls.

However, views are mixed when it comes to the other three political activities - talking publicly about politicians or political parties they support, participating in political protests and becoming politicians themselves.

Respondents in Indonesia and Malaysia generally are the most supportive of political involvement by religious leaders.

Around two-thirds of the respondents in Malaysia and 57 per cent of the respondents in Indonesia say their religious leaders should reveal publicly the politicians or political parties they support.

Conversely, the number hovers between 29 to 47 per cent of respondents in Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Cambodia.

Moreover, 54 per cent of the respondents in Malaysia are keen for their religious leaders to join politics, compared to 48 per cent in Indonesia and 45 per cent in Cambodia.

Less than 30 per cent of the respondents in Sri Lanka, Thailand and Singapore are in favour of their religious leaders becoming politicians.

Despite this, the survey added that most Buddhists in Thailand, Cambodia and Sri Lanka favour basing their national laws on Buddhist dharma – a wide-ranging concept that includes the knowledge, doctrines and practices stemming from Buddha’s teachings.

This perspective is nearly unanimous among Cambodian Buddhists with an overwhelming 96 per cent in favour of basing national laws on Buddhist teachings and practices. Meanwhile, 56 per cent of Buddhists in Thailand share similar sentiments.

Similarly, most Muslims in Malaysia and Indonesia favour making sharia the official law of the land, with 86 per cent of the respondents from Malaysia and 64 per cent in Indonesia supporting this.

BUDDHIST, MUSLIM RESPONDENTS SAY ‘THEIR CULTURE IS SUPERIOR THAN OTHERS’

Respondents among the Buddhist majority in Cambodia and Thailand, as well as among the Muslim majority in Indonesia and Malaysia, say it is important to be a member of their respective religious groups to truly share their national identity.

“Clear majorities across these countries agree with the notion that their ‘culture is superior to others’,” the survey found.

In Cambodia and Thailand, more than 75 per cent of Buddhist respondents say being Buddhist is important to being truly Cambodian or Thai.

Although most people in these countries identify as Buddhist religiously, there was widespread agreement that Buddhism is more than a religion.

Between 76 per cent and 96 per cent of Buddhists in Cambodia and Thailand not only describe Buddhism as “a religion one chooses to follow” but also say Buddhism is “a culture one is part of” and “a family tradition one must follow”.

In some ways, Buddhism’s links to national identity in these countries parallel the role of Islam in Indonesia and Malaysia, the survey found.

Around 86 per cent of Indonesian Muslims say being Muslim is important to be truly Indonesian, followed by 79 per cent of Malaysian Muslims who say being Muslim is important to be truly Malaysian.

Furthermore, Muslims in both countries commonly describe Islam as a culture, family tradition or ethnicity – not just “a religion one chooses to follow”.

For instance, three-quarters of Malaysian Muslims said Islam is “an ethnicity one is born into.”

CAMBODIANS, THAIS AMBIVALENT TOWARDS RELIGIOUS DIVERSITY

Many throughout the countries surveyed – including all major religious groups – express a general acceptance of religious diversity.

For example, more than 60 per cent of those who are part of the large majorities in each country say they would accept followers of other religions as their neighbours.

Most people across the region also describe other religions as peaceful and as compatible with their national culture and values.

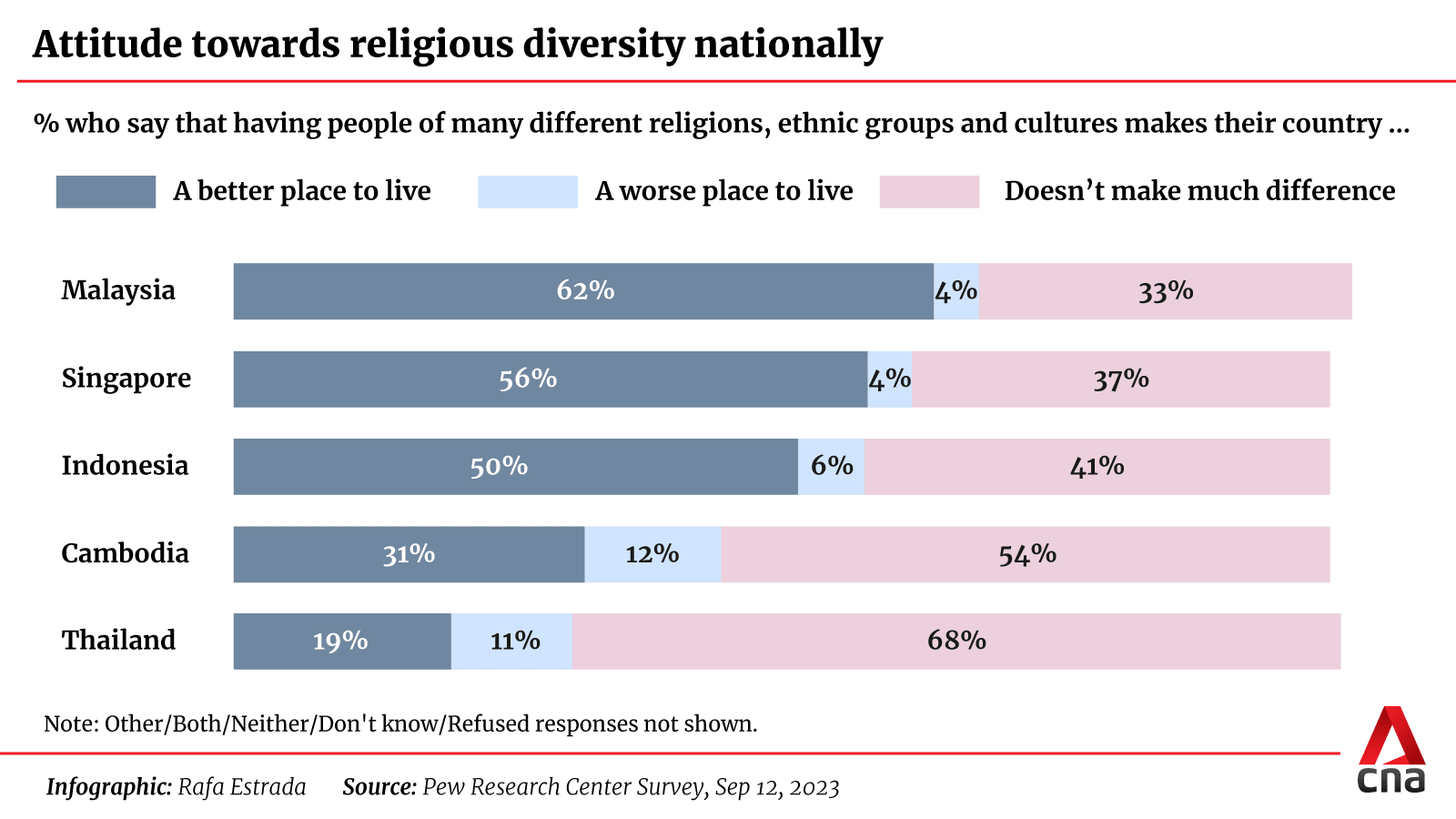

However, a majority of Thai adults and Cambodians take the ambivalent position that religious, ethnic and cultural diversity has neither a positive nor a negative impact on their country.

In Malaysia, 62 per cent of the respondents say that having people from different backgrounds makes their country a better place to live in, while just 4 per cent or fewer say diversity makes their country worse.

On the other hand, the survey noted that just 19 per cent of Thai adults say diversity makes their country better, while 68 per cent say it doesn’t make much difference and 11 per cent say it makes Thailand worse.

Most adults surveyed across the region say they view other religions as very or somewhat peaceful. Far fewer say that other religions are not very, or not at all, peaceful.

Additionally, overwhelming majorities of all major religious groups are willing to accept followers of different religions as neighbours.

Around 72 per cent of Muslim respondents in Malaysia and 68 per cent in Indonesia say they are willing to accept Buddhists as their neighbours.

Meanwhile 77 per cent of Buddhist respondents in Cambodia and 65 per cent in Thailand say they are open to living alongside Muslims.

Researcher Mr Evans told CNA that there are some respondents who do not take a tolerant view, citing how 36 per cent of Thai Buddhists said Islam is not peaceful while 42 per cent of Malaysia Muslims said Buddhism is not peaceful.

However, he maintained that people in all six countries are generally tolerant of other religions.

“Across all major religious groups, most people say they would be willing to accept members of different religious communities as neighbours,” he added.

“And majorities in most countries agree that other religions are compatible with their country’s culture and values.”

When asked to comment on the overall findings, Malaysia political analyst Oh Ei Sun, a senior fellow at the Singapore Institute of International Affairs, told CNA that the results suggests that some countries in Southeast Asia should be wary of "a growing number of apparently very pious people".

In particular, he identified them as those who are keen to impose "very fundamentalist if not extremist versions" of their religion not only to the rest of the country but eventually around the world.

"This would inevitably lead to religiously oriented disputes domestically, regionally and eventually globally, sometimes of a violent nature, that would erupt as other communities would not like to be so subjugated," said Dr Oh.

On what countries can do in response to this concern, he noted that authoritarian governments could adopt "radical measures to ban religious politics or disallow religious leaders from joining politics".

He added that other measures such as educating the masses as well as governments working closely with religious leaders would unlikely succeed and risk the governments being infiltrated by extremist elements, citing how Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence was previously infiltrated by Islamist extremist group the Taliban.