From their school lab in Sabah, students try to turn seaweed into bioplastic to fight marine litter

The trio are experimenting with using local red seaweed to make bioplastic that can degrade in four to six weeks, instead of hundreds of years like conventional plastic.

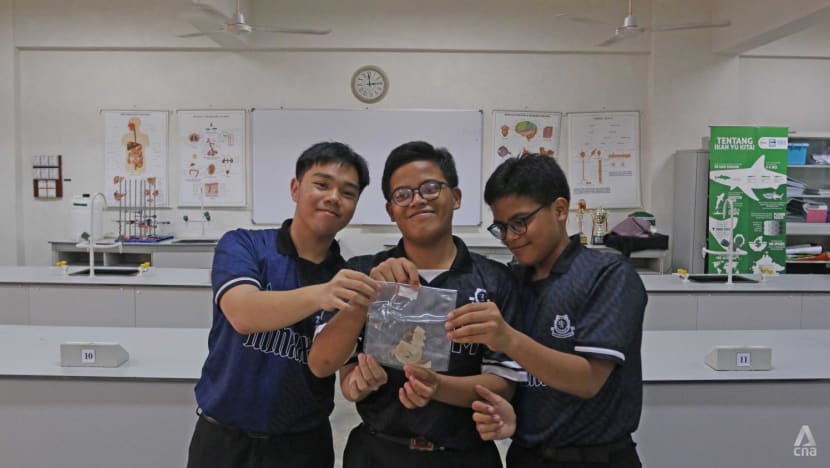

MARA Junior Science College Semporna students (from left) Fahim Nazhan, Muhammad Fauzi Lakarani and Muhammad Fauzan Lakarani are trying to turn seaweed into bioplastic. (Photo: CNA/Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

SEMPORNA, Sabah: The coastal town of Semporna, on the northeastern tip of Sabah, has been dubbed the “gateway to scuba diving paradise” by local media.

The islands near the town are blessed with white beaches and crystal-clear water. One of them is Sipadan, a world-famous and limited-access diving haven teeming with marine life.

But if the islands are paradise, Semporna itself could not be more different.

Near a sprawling market selling everything from dry goods to seafood, a coastal area was covered with trash. On the rocky beach, people in flips-flops sidestepped plastic bottles and containers before climbing onto wooden boats.

At an empty car park, children played football among litter scattered on the asphalt and grass verges.

Over the years, some travel reviews about Semporna painted a similar picture. “Semporna the self-proclaimed gateway to paradise is probably the dirtiest place on earth I have seen so far,” wrote a visitor from Switzerland in a May 2019 Tripadvisor post.

Not all hope is lost, however, if the ambitions of three 16-year-old students at a boarding school not far from Semporna were anything to go by.

Getting to the MARA Junior Science College involves turning off the main highway 20 minutes from Semporna. The bumpy road snakes through a small village before leading up to the campus, nestled between acres of oil palm plantations.

“Semporna is very dirty,” said Fahim Nazhan, a Form 3 student there. “The beaches on the mainland, the water was clear and now it’s turning brown. It’s becoming more polluted.”

Majlis Amanah Rakyat, or MARA, is a government agency that aids and trains Bumiputeras in the areas of business and industry.

According to National Geographic, about 18 billion pounds of plastic waste from coastal regions flow into the oceans every year. This plastic can be very harmful to marine life, for instance when they are mistaken for food or become a choking hazard.

This is what prompted Fahim and two classmates, identical twins Muhammad Fauzan Lakarani and Muhammad Fauzi Lakarani, to pursue an experiment started by their seniors.

They aim to use Kappaphycus, a type of red seaweed commonly found in Sabah, to make bioplastic that can degrade in about four to six weeks, instead of hundreds of years like conventional plastic.

But there are challenges ahead. It is difficult and expensive to create bioplastics that are as durable and waterproof as oil-based plastic, which is produced in large quantities and sold cheaply for everyday use.

Then there is the argument that bioplastic - despite its potential ability to be discarded anywhere and somehow disappear - will not solve plastic pollution, unlike reducing waste and increasing recycling.

Fauzi said he wants seaweed-based bioplastic to be “part of the solution”. “I hope this project can make this world a better place because we can see that plastic is a big problem for our country,” he added.

MAKING SEAWEED BIOPLASTIC

The group decided to start on their project as part of science class last year, armed with secondary school-level science knowledge and experience shared by their seniors.

“We chose seaweed because it is popular in this area,” Fauzi said, noting that they grew up eating seaweed, a dish found in every local eatery. “So, it is easy for us to find our raw material.”

Around the world, companies are also trying to use seaweed - one of the fastest-growing organisms on the planet - to make bioplastic. In 2013, UK start-up Skipping Rocks Lab introduced an edible water bottle made from brown seaweed.

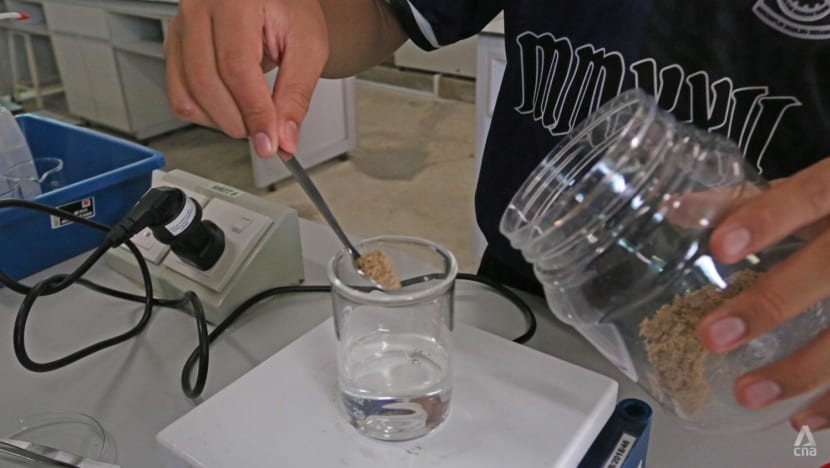

In Sabah, the group bought cheap seaweed from local farmers - or sometimes grabbed it from the beach - and took it to their science lab.

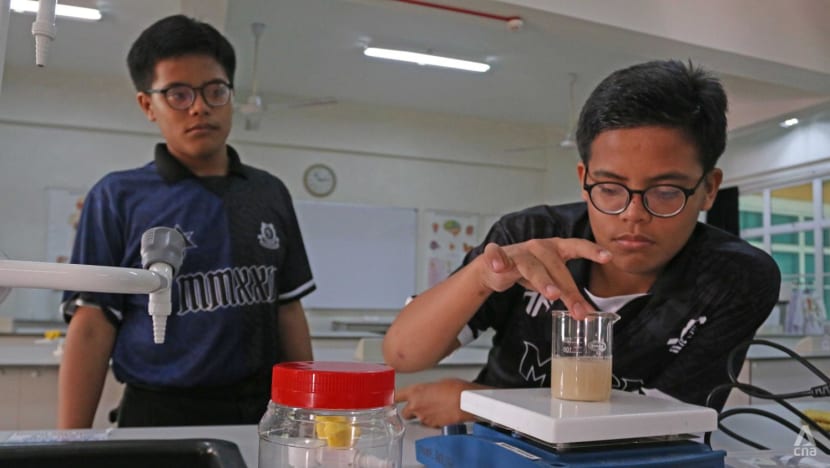

The seaweed is dried for a day, then thrown into a blender to be ground into a powdery-like substance. Water, cornstarch and glycerol are added, then further mixed together for 30 minutes using a magnetic stirrer until it turns almost into jelly.

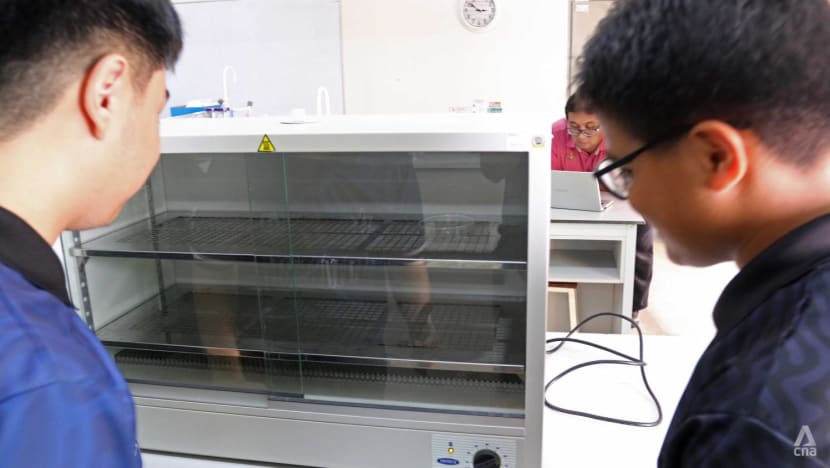

The next and final step is the most critical: The solution is placed in a drying cabinet and heated at 60 degrees Celsius for 12 hours. Anything longer and the solution will burn up, creating a final product that is brown and crumbly.

Fahim, Fauzi and Fauzan have gone through this time-consuming process dozens of times over the past year, largely using trial and error. They have varied the amount of cornstarch and heating durations, trying to determine which combination produces the best result.

The current parameters have led to their best effort to date, a thumb-sized sliver of whitish material that feels somewhat like plastic, but is still too soft and tears far too easily.

Still, it is progress considering the students are only doing this during their free time. Most of their days are taken up by classes and revision. Weekends are reserved for additional lessons and co-curricular activities.

Fauzi described how they spent some nights in the science lab, straining to stay awake and ensuring their product does not overheat. Once, he fell asleep, only to be awakened by a burning smell.

“It is disappointing when this happens because the process takes so long and we have to wait for the results,” Fauzi said.

Nevertheless, the group wants to push on. They aim to come up with a utensil and straw prototype next, although they are not putting a timeline on progress.

They will start taking chemistry classes next year, and they feel this will help them make their product more durable by knowing which chemicals to add to the mixture.

But Fahim stressed that any chemical introduced will have to be in very small quantities, insisting that they do not want their product to harm marine life.

“The target is to commercialise it in Malaysia, maybe internationally,” Fahim said.

CHALLENGES OF SCALING UP

One Sabah-based company that produces seaweed-based bioplastic knows how tough it is to go commercial.

“There are a lot of technical kinks that we have to work out. The industry is quite comfortable with the technical performance of regular plastics,” said Chung Ngin Zhun, who founded Rhodomaxx in 2018.

“It's a dilemma whereby the industry wants something that is biodegradable, but yet they want something that is water-resistant or waterproof. But if anything is able to degrade, it cannot be waterproof.”

Chung believes his company is the first in Malaysia to produce seaweed-based bioplastic and agricultural products. The Sabah native sources the raw material both locally and from countries like Indonesia and the Philippines.

“We have to clean the seaweed and purify it. The amino acids, hormones and fats are all extracted to turn into agricultural inputs, while the cellulose is extracted to turn into the raw material or the precursor chemical for our bioplastics,” he said.

Rhodomaxx has managed to produce a small plastic bag from seaweed, and Chung said its tensile strength - or resistance to breaking - is “quite similar” to low-density polyethylene, the material used to make conventional plastic bags.

Its water resistance, however, is “nothing” compared to that of traditional plastic, so Chung has to find a niche market for his products.

For instance, his products will work with items that are shipped and transported in dry conditions or those that require water-soluble plastic packaging.

Another issue is pricing these products, as Chung highlighted that production costs were “quite high” and the final price “totally dependent” on economies of scale.

While the current plastic industry is supported by large petroleum companies, he said, bioplastic manufacturers do not have the same luxury.

Still, the fact that his company produces two types of seaweed products helps to reduce production costs.

“With bioplastics, it’s a bit more different because it's not really a single source raw material. You have guys who are using tapioca, fiber waste, seaweed or protein,” he explained.

“So, there is no ‘Petronas’ or ‘BP’ for the industry to lean on while it finds its footing, because everyone is doing their own thing. It's quite hard to reach the economy of scale.”

Chung is confident that in terms of production processes and technical specifications, his company is not that far off from making bioplastics mainstream.

“The only thing that is hindering the growth of bioplastics is actually the users of plastics or packaging material themselves,” he said, adding that compromise is needed to balance the advantages and flaws of bioplastics.

Ultimately, Chung thinks that projects like the one by the three students in Semporna are encouraging. He is hopeful that these bottom-up efforts will attract bigger players.

“Hopefully it will go up the chain to policymakers and industry players on how to actually adopt these movements into their everyday practices, rather than just a PR stunt or greenwashing,” he said.

WILL BIOPLASTIC SOLVE MARINE POLLUTION?

With that said, an expert in solid waste management cautioned that bioplastic has some way to go when it comes to solving plastic pollution.

“It has potential, but in reality, we are still facing (issues) in the practicability of applying these biodegradable plastics,” said Haidy Henry Dusim, a senior lecturer in the faculty of science and public policy at the MARA Technological University in Sabah.

“In terms of its resistance, maybe it’s not suitable to replace all types of plastic, especially when we talk about plastic bottles.”

Another concern, Haidy said, is that bioplastics could further encourage littering and pose more problems for waste management.

“It could be eco-friendly. But if the attitude is still to throw it away, not managing solid waste, that is another problem,” he said.

He said that local governments in Malaysia should also introduce laws for mandatory waste separation to increase recycling rates, and enforce more strictly against littering.

In 2019, the Star reported that authorities in Semporna started an “all-out war” against litterbugs, on the orders of then-Sabah chief minister Shafie Apdal.

At least nine offenders were caught in a single day, and ordered to pay an RM500 (US$113) fine or do corrective clean-up work.

The latter option had a catch: They had to wear a vest with the word “monyet” (monkey) on it, in line with the council’s anti-litter theme that states only monkeys throw rubbish indiscriminately.

PRESSING AHEAD

Back at MARA Junior Science College, teacher Shahrul Hafiz Abdul Ghani, who mentors the seaweed project, said it is important not to just raise awareness about littering, but to also create alternatives to plastic.

Shahrul said he would oversee the project through his students’ five-year programme, noting that financially they are currently only supported by the school and sometimes his own money.

“If we can get another prototype, maybe in the future we can find an investor to invest in this project. I hope it can become a great product to sell and reduce the impact of pollution,” he said.

For now, the students seem to be on the right track. In Form 2, their project emerged second out of about 400 school entries in a national science and innovation competition sponsored by Samsung.

They were disappointed to finish behind a water purification project, saying the judges thought their prototype was not close enough to actual plastic.

“If we were already making plastic, I don’t think we have to go to school anymore,” Fahim said with a laugh.

They also gave some of their winnings - RM25,000 worth of handphones, tablets and earbuds - to their seniors, saying this would not have been possible without their initial research and trials.

Nevertheless, coming in second is no mean feat for this small, rural school, and the unexpected success has made them even more determined to achieve greater things.

“I don’t know (if we will succeed), but we will try. We need the confidence but we also need to do more research,” Fahim added.

Read this story in Bahasa Melayu here.

Read this story in Bahasa Indonesia here.