analysis Asia

Has domestic politics in Thailand and Cambodia fuelled latest border flare-up?

Border clashes between Thailand and Cambodia are intensifying, driven by political insecurity and economic pressures in both capitals. Analysts warn the fragile ceasefire is close to collapse.

A Thai military personnel walks near the Thai-Cambodian border at Chong Chub Ta Mok area, in Surin Province, Thailand, on Aug 20, 2025. (File Photo: Reuters/Chalinee Thirasupa)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BANGKOK: Deadly military operations have reignited along the contested Thai-Cambodia border in recent days, with experts warning that the violence could be linked to and prolonged by the two governments grappling with vulnerabilities and political pressures.

In particular, domestic issues and fragile command structures in Thailand and economic unease in Phnom Penh have converged to turn the border tension into a far sharper confrontation than analysts expected.

The escalation comes as the three-month-old government of Thai Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul faces criticisms over several issues - including its handling of deadly floods in southern Thailand - ahead of a general election expected in March next year.

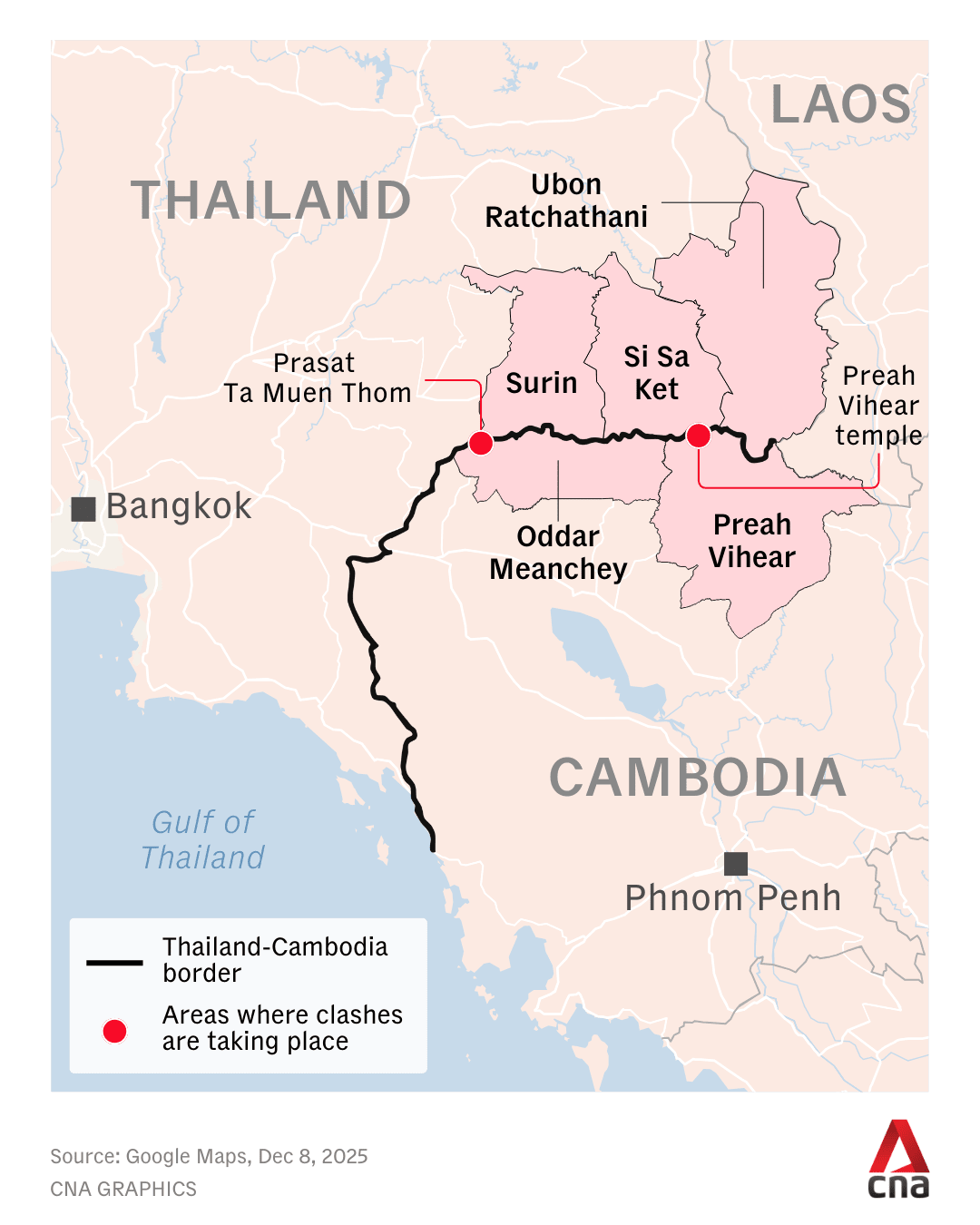

Hostilities resumed on Sunday (Dec 7), with at least six Cambodians and one Thai soldier killed in the fighting. Each side has blamed the other for provoking the military actions, which included air strikes from Thai fighter aircraft and reports of exchanges of fire over multiple fronts.

Thousands of civilians have been evacuated to safe zones, only months after the previous round of clashes in July claimed the lives of at least 48 people, saw bilateral trade decimated and up to a million migrant workers flee Thailand, with many yet to return.

Amid the rising tensions, the National Olympic Committee of Cambodia (NOCC) pulled its entire sporting delegation out of the 33rd SEA Games on Wednesday morning.

For more than a century, Thailand and Cambodia have been at odds over sections of their shared border - an area that has never been fully demarcated.

But with both governments under pressure and the border’s long history of miscalculation, even minor incidents now hold the potential to escalate rapidly, experts said.

“Domestic pressure is palpable on both sides,” said Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a professor of International Relations at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.

THAILAND’S DOMESTIC TURMOIL

The Thai government has entered this situation in a position of deepening political weakness domestically, analysts said, complicating the next steps to escalating or easing the fighting.

The escalation follows devastating floods in southern Thailand, criticism over the organisation of the SEA Games and reports about alleged links between Prime Minister Anutin and regional scam networks.

These challenges “surprisingly and unexpectedly” tanked the popularity of the prime minister, who came into office in September, and his Bhumjaithai party, said Panitan Wattanayagorn, an independent expert on international relations and security affairs.

A recent poll by Suan Dusit University - conducted during the peak of the southern floods late last month - found that Anutin’s public support had plunged from 48 per cent down to 23 per cent.

Anutin now has incentive to “divert attention” away from some of those issues ahead of elections.

He “also benefits from rising nationalism at home, which gives him an edge going into the poll”, Thitinan said.

The uptick in fighting was a clear “diversionary tactic”, said Vannarith Chheang, a lecturer in public policy and global affairs at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

“It's a natural kind of instinct of politicians, especially before elections. I think Cambodia has been prepared for this scenario but we did not expect this kind of large-scale bombardment,” he said.

But due to opaque power structures between the civilian government and powerful military in Thailand, the situation is likely more complex than Anutin simply wanting to pick a fight for his own re-election purposes, said Panitan, a veteran observer of Thai politics who previously held senior roles in government, including as chairman of the prime minister’s Security Advisory Committee.

“On one hand, Cambodia is trying to seize this opportunity. Of course, the Thai leadership may also have wanted to take this opportunity. But for the Thai side, it is much more complicated, as the command of the military is not controlled totally by Anutin,” he said.

He added that while Anutin appeared to have better connections with senior army figures compared to the previous government of Paetongtarn Shinawatra, he naturally lacked authority compared to military-linked prime ministers of the near past, like Prayut Chan-o-cha who was in office from 2014 to 2023.

Prayut was the Thai army chief before seizing power in a coup against Yingluck Shinawatra and becoming prime minister.

Anutin took over from Paetongtarn, who officially stepped down in August after a court ruled that she had breached ethical norms and damaged the reputation of the country over a leaked phone call with former Cambodian leader Hun Sen.

Anutin’s criticised handling of the flood situation, widely deemed slow and lacking coordination, was evidence that he was still struggling to act as a commander-in-chief with the backing of the military, Panitan said.

While a victory on the battlefield or gaining concessions from Phnom Penh would reap “enormous benefits”, he did not believe those incentives would be sufficient to provoke the fighting.

Overall, the situation has left Anutin feeling “politically insecure” and being forced to rely on traditional institutions, like the military, for help, Thitinan said.

With power over the border situation broadly in the hands of the military, the results could be unpredictable and more difficult to control for the country’s inexperienced and besieged premier, he added.

“The Anutin government has essentially outsourced border policy to the Thai army. The army is designed to fight, not for diplomacy and peace making.”

CAMBODIA’S OWN PRESSURES

All of these struggles and dynamics would have been keenly observed by the top leadership in Cambodia, who may currently see Thai leadership as weak or fragmented, said Panitan.

The history of this conflict over several decades has shown that Cambodia often exerts more pressure on civilian rulers and shows compromise with military-aligned leaders in Thailand, he said.

For example, during the 2008–2011 Preah Vihear tensions, Cambodia exchanged sharper diplomatic language and engaged in repeated border clashes at times when Thailand’s elected governments were weakened by protests, coalition fragility and rapid leadership turnover.

However, relations stabilised and clashes muted during Prayut’s period of leadership.

Analysts say Cambodia is under its own political and economic pressures, which may be shaping its posture along the border.

The Asian Development Bank recently trimmed its projection for Cambodia’s 2025 GDP growth from roughly 6.1 per cent down to 4.9 per cent, partly due to border-tension risks.

The surge of returning indebted migrant workers needing employment and the spread of scam centre operations in Cambodia are also showing signs of creating serious economic and social pressures.

A 2025 report from the US Department of State identified “a government pattern of human trafficking in online scam operations”. Multiple entities in the country attracted US sanctions in September for involvement in the industry.

Because of Cambodia’s internal politics, “there remains a need to project state capability and strength”, said Dulyapak Preecharush, an associate professor of Asian Studies at Thammasat University.

Chheang added that the conflict is having the effect of raising national pride among Khmer youth and embedding feelings of resilience among the population.

“If we live in peace too long, we forget about the importance of national unity, determination, those kinds of things,” he said.

A FRAGILE BORDER AND MEDIATION STRAINS

The truth about which side is provoking which probably lies somewhere in the middle, whereby the timing of the escalation of fighting “reflects the inherent fragility” of the border, according to Dulyapak.

And even where issues may not be directly related at all, public perceptions can link them into a single picture of weakened governance: whether in disaster management, economic issues or security affairs, he said.

The groundwork for rising tensions had already been laid last month.

In November, Thailand already suspended agreed-upon de-escalation measures, after one of its soldiers was injured by a landmine that Bangkok claimed had been newly laid by Cambodia.

The Thai government demanded an apology, otherwise it would not restore the terms of the ceasefire. Since then, the situation has spiralled further.

While the unsteady peace agreement brokered by the United States and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has not been entirely abandoned, it is severely imperilled.

“The peace accord is pretty much in tatters at this point,” said independent political advisor Jay Harriman.

President Donald Trump was a key figure in bringing national leaders to the negotiating table in July, holding tariffs over both nations as leverage to ensure peace, observers said.

Following the resumption of fighting, a senior Trump administration official said on Monday that the US president expects Cambodia and Thailand to “fully honour” their ceasefire commitments.

"President Trump is committed to the continued cessation of violence and expects the governments of Cambodia and Thailand to fully honour their commitments to end this conflict," said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, as cited by various media outlets.

But the Anutin administration has shown signs of being somewhat at odds with Washington, following the suspension of the ceasefire agreement.

Last month, the US Trade Representative paused negotiations with Thailand under the Trade and Investment Framework Agreement, saying discussions would resume “once the Thai side commits to complying with the joint statement”.

It prompted a rebuke from Thailand's foreign ministry. “Security and safety issues … must be considered separate from trade issues,” said its spokesman Nikorndej Balankura on Nov 15.

Bangkok may have been expecting a more sympathetic Washington, given the long history of Thai-US cooperation, argued Paul Chambers, a visiting fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, in a paper published last month.

Both sides are also navigating the competing influence of major powers, with Cambodia closely aligned to China and Thailand attempting to balance long-standing ties with the US against a deepening economic relationship with Beijing.

Thailand is one of two defence treaty allies of the US in Southeast Asia, the other being the Philippines.

“Had Cambodia remained close to China rather than seeking to also accommodate Trump, the US president may have been more likely to take Thailand’s side.

"However, Washington has also been irritated by Bangkok’s apparent tilt toward Beijing, as seen in the forced Uyghur deportation and apparent allowing of Chinese ‘tariff-washing’ through Thailand,” Chambers said.

In late February, Thailand deported around 40 Uyghur men, many of whom had spent years in Thai detention, back to China. It prompted backlash from several Western governments, including the US, which had made offers to resettle the men that were ultimately rejected by Bangkok.

It undermined Thailand-US relations at a time when Bangkok needed to navigate and negotiate a tariff deal in Washington, Thitinan wrote in May.

"Tariff-washing" is where Chinese manufacturers facing steep US tariffs shifted production or routing to Thailand to take advantage of Bangkok’s more favourable access to the American market.

The Paetongtarn government vowed to end such practices, but friction has risen in the relationship with Washington, which was keen to increase its economic leverage with Beijing, Chambers said.

Further statements from the then US Ambassador nominee to Thailand, Sean O’Neill “underscored that Washington’s support depended on Thailand aligning with its transactional priorities, not historical bilateral ties”, he said.

ASEAN TO STEP UP?

With the likelihood of the war deteriorating in the near term, it could be up to the regional bloc, and the ASEAN leadership under Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, to bring both sides to the negotiating table again, Thitinan said.

“President Trump may decide to use trade as leverage again but the role of ASEAN is critical at this time. ASEAN needs to arrange a peace-keeping team, not just observers,” he said.

“The immediate days ahead are critical and both sides must be persuaded to step back from what is now ASEAN's worst war between member states in 58 years.”

Chheang agreed that ASEAN needed to be “bolder and more decisive”. “It needs to be brave, courageous,” he said.

The Philippines will be ASEAN chair in 2026.

If Cambodia receives the loud public message being sent by Thailand’s political leadership - namely that the country’s military is ready to preserve natural interests, take control of borders and eliminate threats - Anutin may be banking on being able to negotiate bilaterally, Panitan said.

“I think Anutin and his administration are hoping that Hun Sen and Hun Manet and the leadership in Cambodia get this message and in the end, will come to negotiate so they don't have to go into total war,” he said, an outcome that both sides would most likely want to avoid.

A prolonged conflict would further disrupt cross-border trade, potentially trigger new waves of displacement and retest ASEAN’s ability to prevent disputes between its own members.

Yet for now, observers said, the fragile ceasefire holds only in name, and the political pressures driving the conflict show no signs of easing.

Additional reporting by Jarupat Karunyaprasit.