Duped into taking a ‘business development’ job, he was ill-treated, forced to scam by a syndicate

For three weeks, Malaysian Bilce Tan was held hostage and had to scam others to survive. He secretly gathered evidence to expose his captors. Now, he gives CNA Insider the details of life and work in a Cambodian scam compound.

Bilce Tan, 42, is a manufacturing manager who lives and works in Malaysia. This is an edited version of his story, as told to CNA Insider.

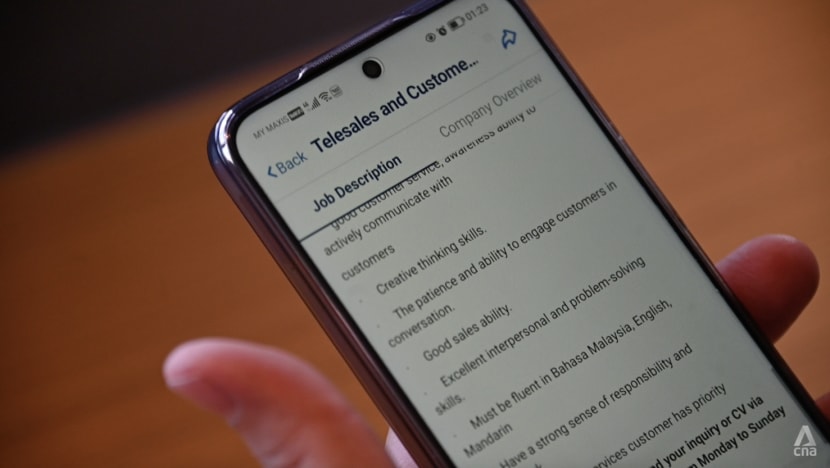

KUALA LUMPUR: When I came across the job ad last April, I didn’t think anything was amiss.

A Malaysian company was seeking someone to manage a customer service team and develop new business opportunities for the company. The only thing that struck me was that the job was in Cambodia.

Cambodia had recently been in the news and not for a good reason: There were cases of Malaysians being duped into going over for work and ending up a hostage. But those people were dumb — there’s no way it can happen to me, I thought.

I’m a University of Malaya graduate who worked in China as a manager for years. But thanks to the pandemic, I was stuck in Malaysia and needed to feed my family. My wife, who’s Indonesian, is still in China, and our 10-year-old son is living in Penang with my parents.

The job in Cambodia looked attractive, with a monthly salary of RM5,000 (S$1,500) to RM10,000 as well as bonuses for good performance. My food and accommodation would be covered, along with the return fare. (CNA Insider has reviewed Tan’s letter of offer from the Malaysian company.)

So why not, I thought? The application process wasn’t easy; I had to pass four rounds of interviews, and the questions asked were related to my managerial experience, such as how I’d deal with employees who lack motivation and how I’d resolve operational issues.

The interviewers even helped me create career plans for my time in the company and assured me the company was recognised by the Cambodian government.

I had no trace of doubt at that time.

On May 6, I boarded a flight to Phnom Penh. I had no idea I was about to go through quite an ordeal.

I FELT LIKE A HOSTAGE

A local man met me at the airport, and I got into his car for the journey to Sihanoukville. It’s about a four-and-a-half-hour ride.

Halfway through, he turned into a petrol station to fill his tank and buy some snacks. That was when three other men got into the car, telling me to move to the back seat.

One sat next to the driver, another behind me and the last one next to me.

I thought they were new employees like me, so I said hello and asked if they were reporting for work like I was. All they told me was that they worked for the company.

But as the driver locked the doors and continued the journey, I felt it was strange that they didn’t seem friendly.

I continued asking questions: where we were going, how long we’d take and which part of Cambodia they were from.

“Just sit, and be quiet,” I was told sternly. “You’ll know when you’re there.”

Something felt wrong. Why did I feel like a hostage? But I didn’t have a choice — I was sandwiched between them in the car, so I had to follow them.

Eventually, we came to the bottom of a hill. It was almost 1am, and I was tired from travelling all day. There were many guards there, all in black, and some were carrying guns. I even saw some guard dogs.

Wow, I thought. Wasn’t I just going to a company to work? Why do I feel like I’m entering a thieves’ den?

When we reached the top of the hill, I was ordered out of the car, and I could smell the sea.

A man body-searched me, opened my luggage — containing all the clothes I’d packed so neatly — and threw everything to the ground.

I got mad, but he told me it was precautionary, albeit necessary, because there’d been outsiders who’d brought in drugs.

It was a huge compound, with many tall buildings that looked like apartments, some office buildings and even a few KTV outlets. I could hear loud music and singing coming from some of them. I could see many people walking around freely. It felt lively.

What exactly is the situation here, I wondered.

THE WORD ‘SCAM’ WAS NEVER USED

By this time, it was very late. The man took me on a quick tour of what he said would be my office. It looked normal, with two long tables, a few computers on each table and a lot of mobile phones.

But what surprised me was that even at that hour, there were people still at work.

The man told me he would make the introductions — and tell me what I’d be doing — the next day. In the meantime, I was to go to my assigned dormitory and get some sleep.

At that point, I still had all my stuff, my passport and mobile phone included. But he warned me not to take photos or videos. When I asked why, he told me not to ask questions.

Everything felt strange to me. But since I was already there, I might as well see what the next steps are, I thought.

The next day, I was taken to the HR office to get my security pass. It was green and had a bar code.

I found out that the green pass meant I was of the lowest rank and couldn’t leave the compound or move around freely. There were other people with different-coloured passes, who were allowed to go out.

When I questioned this, I was told it was for my own safety and that the others needed to go out to “handle matters” and represent the company.

Then I was taken to the office to begin my training. That was when I found out what I was really going to do.

I’d be an “expert consultant” and would need to forge connections with people online to find business opportunities. The company would provide us with accounts, for example on matchmaking sites, Facebook and Instagram, to find people who we’d ask to join our cryptocurrency investments.

I asked my supervisor why. What exactly are we doing?

He said: “We want to give people a sense of security, make them feel like we’re their friend and soulmate. We can make their lives better just by talking to them.” And, he added, our job is very noble.

It all sounded professional. The word “scam” was never used. But in my heart, I was laughing at him. “You’re just scamming people,” I thought. “Why do you even need to say so much?”

LOOKING FOR ‘KEY CUSTOMERS’

I learnt what to do by sitting beside my colleagues and watching what they did. My first task was to transfer money from banks in Singapore, Malaysia and other countries to Cambodia or other overseas banks.

Once I see the (victims’) money has come in, I was told, I must transfer it out immediately. This was to prevent the money from being frozen, which I was told would impact the company’s “profit and loss”.

Then I moved on to social media sites. I had eight accounts, which all featured pictures of beautiful young ladies. The accounts were packaged well, I think by what I knew as the IT or strategy department.

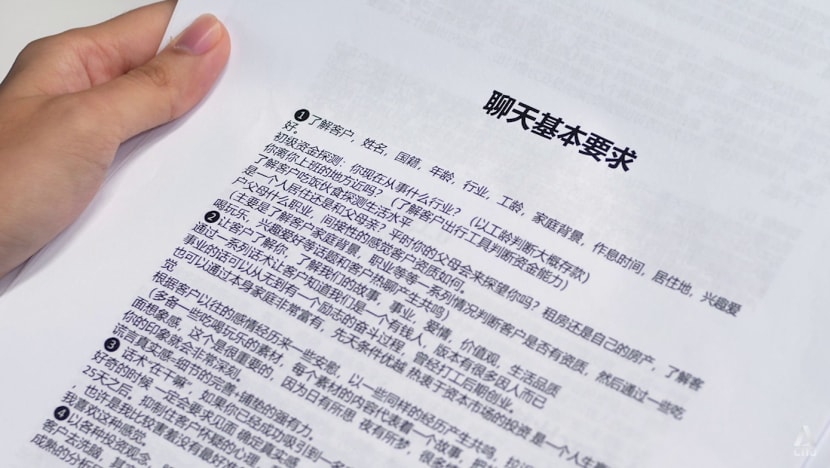

Scripts were then handed to me, written by the “emotional experts” and designed to get the people we meet to like us.

Some lists of names — of Malaysians and Singaporeans — were also handed to me. There were full names, identification numbers, employment data and even salary information. This was how we were to find our “key customers”.

When I asked where all these came from, I was told brusquely that I didn’t need to know.

My persona was a young girl, and I was to target retirees because they “definitely have savings in the bank”. Single mothers were also targeted by others using male personas. They were a popular target because they tend to be lonely, I was told.

There was one elderly man I almost managed to scam. He was a Malaysian widower, and we chatted in Malay. Every morning, I’d show concern for him and ask him what he ate. I’d then send him videos of things I was “cooking”, like fish head soup.

You’d see in the video that I was a young lady with a slender frame. I also sent him voice messages voiced by a female.

All this was done by the IT department, which would send me these things whenever I needed them. You could say my job was basically typing out stuff and forwarding things.

WATCH: How a job scam turned me into a scammer. I’m still seeking justice (22:54)

This elderly man asked me for video calls, and I’d come up with excuses to avoid making any. I told him I was assigned to work overseas, and the different time zones didn’t work for us.

I could sense that he was opening up to me, and I was persuading him to invest RM15,000 in a project. But when it was time to close the deal, I couldn’t do it.

He wasn’t earning much — maybe RM3,000 a month — had three children to take care of and his mother’s health wasn’t good. So every time my supervisor asked me about the progress of this deal, I played dumb. I didn’t want to cause a family to fall apart.

Read our two-part investigative special:

I WANTED TO ESCAPE

You might wonder why I agreed to go along with this job. The truth is I had no choice.

We could’ve told those we were chatting to that we were stuck and forced to scam people. But our supervisor was sitting in front of a huge screen in a different room where he could monitor everything we were typing on the phones and computers.

Everything we said could also be heard, down to the small talk I made with people beside me.

I worked 15-hour shifts and shared a hostel room with four others. I wasn’t allowed to leave the hostel unless I was going to the office, the convenience store or the canteen.

The canteen was huge. It probably could hold up to a few thousand people. That was how I met other people. By listening to their conversations, I realised some were from China, some from Myanmar. There were also Indonesians, Filipinos and even Singaporeans.

We’d greet each other, but I didn’t dare say too much because I realised some of the people I’d met were there willingly.

When I could, however, I discreetly asked some people about the possibility of escaping. I was told flatly that it was impossible and that if I were caught, I’d be tortured or sold to other scam syndicates.

But I couldn’t take this lying down. I wanted to expose what they were doing, gather as much evidence as I could and then try to get out.

So I secretly filmed and uploaded everything to my Google drive. It wasn’t easy, but I tried my best. During shift changes, when other people came in to take my place, I’d hold up my phone and pretend to send a message, but actually I’d be filming or taking photos.

They’d been telling me not to take photos and videos, which showed that they had something to hide. That made me all the more determined. But things soon came to a head.

On the night I first got here, I was told to text my family to let them know that I’d arrived safely and would contact them again after I received my pay. I wasn’t sure if I was being watched, so I didn’t dare say anything else to them.

But I decided to call my family and some friends a week later. Some of them didn’t pick up, but my wife did. I said I was stuck in Cambodia and asked her to call the police. But she told me it wasn’t possible and that I must be overthinking.

I couldn’t convince her that I was serious and really needed help, so I left messages for my friends and gave them as many details of my whereabouts as I knew. Then I switched off the room lights and tried to sleep.

Within half an hour, seven or eight men barged in, pulled me out of bed and pinned me to the ground. One of them showed me an electronic device with a screen and told me to look carefully. “Was this phone call made by you?” he demanded. “Did you call the police?”

I was shocked. How could they have caught me? They slapped me and insisted that I was lying about not calling the police.

Then they searched the room. I’d brought three mobile phones with me and hidden them around the room. They found all three and forced me to unlock my phones. That was when they found the videos and photos I’d taken.

I thought I was done for — the only thing I didn’t know was how I’d die. Would I be thrown into the sea? Or buried alive?

In the end, they threw me into a small room and locked me inside. It was completely dark, and there was no toilet, only a small exhaust fan. I was there for two days and was only given plain rice with a little sauce to eat.

But I couldn’t eat anything. How could I, in that smelly room?

I felt as if my hair had turned white overnight. Maybe this is where my life will end. But at the end of the second day, they let me out. They asked me: “Does it feel good? Was it great to be inside?”

I was stripped naked, and they took photos and videos. Then they wanted to film me bringing a piece of luggage to a car, hugging everyone and saying goodbye as well as saying hello from the inside. I realised this was so they could claim that I hadn’t been forced to be there.

After that, they warned me. “You have two choices,” they said. “Either you continue to work or we won’t let you stay in Cambodia.”

This, I knew, meant they’d sell me to another syndicate that could move me to other countries, like Myanmar. I was too afraid to do anything but comply. Then they sent me back to work.

All my phones were gone. And they treated me more harshly: They’d shout at me and threaten to throw chairs at me.

I lost hope. Every time I went for a meal, I looked round for anyone who could help me escape. But there was no one. People there were scared to die and didn’t have the courage to try escaping.

But I didn’t want to stay. I wanted to escape, and eventually I did.

I made it back to Malaysia — three weeks after I’d left — with someone’s help. I can’t say much because I don’t want to put this person’s life in danger, but let me say this person is my angel.

SUED FOR DEFAMATION

The first thing I did after my flight landed in Kuala Lumpur was to make a police report. But I was told the police in Penang would have to handle the case because that’s my home town.

I was upset, however, when I went to Penang. The police officer didn’t seem like he cared. He was even eating chips while talking to me. His colleague beside him was playing games on his phone. I got the impression that they didn’t think my case was a big deal.

Later on, I found out that when the scammers took away my phones, they got access to my personal details. They locked me out of my email and social media accounts. They even managed to transfer all the money out of my bank accounts in China.

This was at the end of May. When I made follow-up calls to the police, the inspector in charge of my case didn’t pick up once.

In total, I made three police reports in May and June. (Tan shared copies of the reports with CNA Insider. The Royal Malaysia Police did not respond to CNA Insider’s queries about updates on the reports Tan had made.)

I felt angry and wronged, so I went online to look for people who could help me. Through Google, I found out about the Global Anti-Scam Organisation (Gaso), which helped me spread the word about what I’d gone through.

Its founder helped me a lot. She introduced me to reporters, I also met some MPs, and we even held a press conference.

But July was when I got a lawyer’s letter. A person in the company I’d interviewed for was suing me for defamation, saying I’d made up stories because I owed the company money. (CNA Insider reached out to the plaintiff’s lawyers for comment, and they replied that they were unable to disclose any information regarding ongoing court proceedings.)

Some people even called my wife in China. They must’ve got her contact number from my phone. Our already strained relationship — after we’d been separated for more than two years owing to the pandemic — was made worse by this incident.

I don’t know what they said, but she was upset. “Why did you give our information to outsiders?” she asked me. She said she was afraid to talk to me, and that was the last time I heard from her.

She has blocked me. When I tried using my father’s phone to contact her, she blocked him too. When I reached out to her parents, her father said she wanted a divorce.

Our relationship had lasted for seven years — that’s not a short period of time.

I hope she’ll see this interview and understand what happened to me in Cambodia. I can swear to the gods that I didn’t do any disservice to you. Please give me a chance to explain, even if it’s for just five to 10 minutes.

In November, I got help from an NGO, the Malaysian International Humanitarian Organisation. At the request of its adviser, former inspector-general of police Musa Hassan, the police assigned an officer in a specialist anti-trafficking unit to take my statement.

Last month, the officer in charge of the case told me investigations were ongoing. He didn’t give me any more details.

I’m now relying on donations from the public to fight my case in court. I’m really worried as I’m up against a large organisation.

I’d thought the people who were scammed into going to Cambodia were dumb, but it turns out that I’m just like them. I never thought this would happen to me, but it did.

(Editorial note: Many of the details of Tan’s story could not be independently verified by CNA Insider. However, his account matches the experiences of many other job scam victims put to work by scam syndicates.)

Text: Lianne Chia, Ray Yeh

To read more first-person accounts by scam victims and former scammers, explore our microsite: Scammers Exposed.