Why young Indonesians want to ‘run away’ from the country, and the cost of a brain drain

Given limited opportunities at home, young Indonesians are using the hashtag, #KaburAjaDulu (#JustRunAwayFirst), as a call to their generation to go overseas. What must the country do to persuade them to stay, asks the programme Insight.

Jobseeker Candra Arifiyanto is considering working in Australia, even if he has to leave behind his family in Jakarta.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

JAKARTA and BANGKOK: Each morning in Bangkok, Edwin Yusuf Abdullah checks hotel booking data and adjusts room prices accordingly.

The hotel revenue strategist had been in the same field in Jakarta for more than a decade. But in Thailand, his salary is 50 to 60 per cent higher.

“Actually, my skill is quite needed in Indonesia. But it goes back to compensation,” said the 39-year-old. “I’m more appreciated in Thailand than in Indonesia.”

The move overseas in 2023, however, meant leaving behind his 11-year-old son, who lives with his ex-wife. To support his family, he sends 80,000 baht (US$2,500) home every month and has set up a fund for his son’s university education.

“Of course I feel sad about leaving my son,” he said. “(But) at some point, I’ll definitely go back to Indonesia. I’m doing this for (his) welfare.”

From Bangkok, he has watched a phrase go viral on Indonesian social media: #KaburAjaDulu. The hashtag meaning “just run away first” began trending early this year and has appeared in more than 200,000 TikTok posts, for example.

The hashtag will continue to be used for a while, he thinks. “(Young people) feel they don’t have a hope of developing themselves in Indonesia.”

Social media executive Fina Agustina, 26, shares the sentiment and has interviewed for a job in Spain. Her current work brought her to Jakarta, where she stays in a boarding house in a packed neighbourhood.

“#KaburAjaDulu isn’t just a hashtag,” she said. “It’s a way for people to express their anxiety because they feel the government has made things unbearable.”

A survey done in March by research firm Populix found that all its 1,000 Indonesian respondents wanted to leave the country, with 82 per cent citing higher income overseas. Career development and better quality of life were among other reasons.

Most of the respondents were between 18 and 35 years old, had a degree or a diploma and were from a middle-class or higher socio-economic background.

“When they look at what’s available here versus what’s available out there, they’re of course enticed to go for opportunities elsewhere,” said Populix co-founder and chief executive officer Timothy Astandu.

Is Indonesia faced with not only a social media trend but a risk of an accelerating brain drain of its young, bright sparks? The programme, Insight, looks at what is behind their discontent and what can be done about it.

WATCH: Young Indonesians want out of their country — But will they return? (46:43)

“PEOPLE ARE BECOMING DISILLUSIONED”

Unlike earlier waves of migration, the #KaburAjaDulu movement involves those “in their most productive years” and who “tend to be more well-educated, … more (open-minded) about the world”, said Timothy.

“There’s a sense that people are becoming disillusioned with the expected progress in terms of what jobs are available, what quality of life they should be having, … what things they can afford … versus what they’re getting right now,” he added.

“So they’re thinking that the grass is greener on the other side.”

The call to go overseas resonates with Candra Arifiyanto, 36, a jobseeker in Jakarta.

After graduating in German studies in 2016, he pivoted to the healthcare industry, gaining skills in sales and business development. But when his recent contract with a medical software firm was not extended, he was back to square one.

He sent out more than 50 job applications with little success. One multinational company seemed ready to hire him but pulled out, citing factors such as the political situation and recent protests, he recounted.

“I was hoping to get an offer letter, but it didn’t happen because of the current situation,” said Candra, who described #KaburAjaDulu as “a form of emotional outburst or disappointment … with the government’s lack of action”.

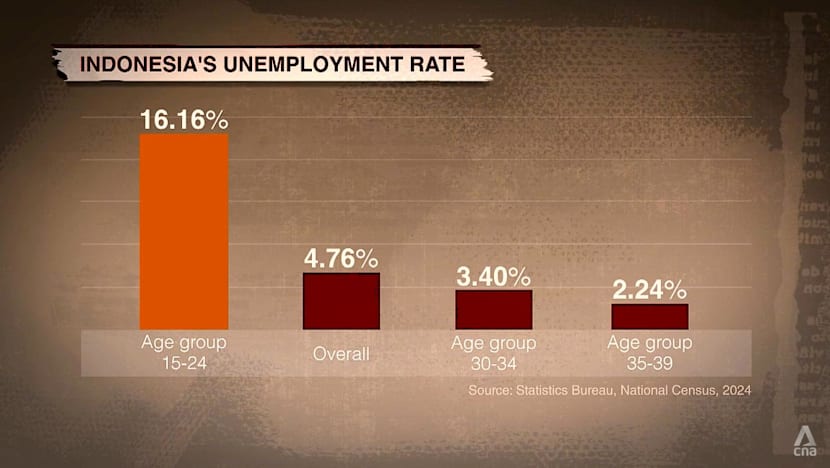

He is one of roughly 7 million unemployed Indonesians, who comprise close to 5 per cent of the country’s labour force. Among them are more than a million university graduates.

The youth are especially hard-hit. The unemployment rate among those aged 15 to 24 is more than 16 per cent.

The scale of the problem is visible at job fairs. A recent fair in Bekasi city, West Java, saw 25,000 people jostling for 2,000 openings.

“Obviously, we have a big population, … and the economy has to grow in the right way in order to give them the jobs,” said Timothy.

“There’s also a mismatch between the jobs that are available and the kind of young people we’re producing.”

That mismatch is tied to Indonesia’s shifting economy. The gross domestic product contribution from manufacturing, for instance, has shrunk from more than 28 per cent in 2004 to close to 19 per cent.

“The (manufacturing) industry can no longer absorb workers and support the economy,” said Nailul Huda, the director of digital economy at the Centre of Economic and Law Studies.

Government belt-tightening has added further pressure to Indonesia’s job market. President Prabowo Subianto ordered budget cuts worth 306.7 trillion rupiah (US$18.4 billion) for this year, affecting spending on ceremonies and travel, for instance.

“This efficiency drive affects the organising of events at hotels or travelling within Indonesia. This can kill the industry,” warned Nailul.

The Jakarta chapter of the Indonesian Hotel and Restaurant Association surveyed hospitality businesses in April and found that a majority were planning to reduce their workforce by 10 to 30 per cent.

With the difficulties in the formal economy, more young people are turning to informal employment — 44.3 per cent of employed youth aged 16 to 30 in 2023, up from 39.6 per cent in 2019. This means lower pay and no social protection.

That is not an option for Candra. He is looking at countries like Australia, even if it means leaving behind his wife, daughter and parents. “What’s important is to leave Indonesia first,” he said.

INDONESIA COULD LOSE UP TO US$1B A YEAR

The sense of frustration among Indonesian youth points to the risk of a bigger outflow of skilled citizens.

Last year, Indonesia ranked 90th out of 179 countries in the United States-based Fund for Peace’s human flight and brain drain indicator — among the worst in Southeast Asia, after Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia.

The economic consequences could be serious if more people leave. Centre for Welfare Studies (Prakarsa) executive director Ah Maftuchan estimates annual losses at US$500 million to US$1 billion, factoring in lost productivity and tax revenue and other ripple effects.

“These are the right people who can build the country,” said Timothy. “To lose a significant chunk of this particular demographic is the most damaging.”

Economic headwinds add to the gloom. The rupiah slumped to a record low in April before recovering slightly.

Layoffs climbed from nearly 65,000 in 2023 to about 78,000 last year. Given the global trade tensions and US import tariffs, experts warn of more layoffs.

Foreign direct investment has risen in recent years but mostly in capital-intensive industries, with a less direct impact on employment, highlighted Maftuchan.

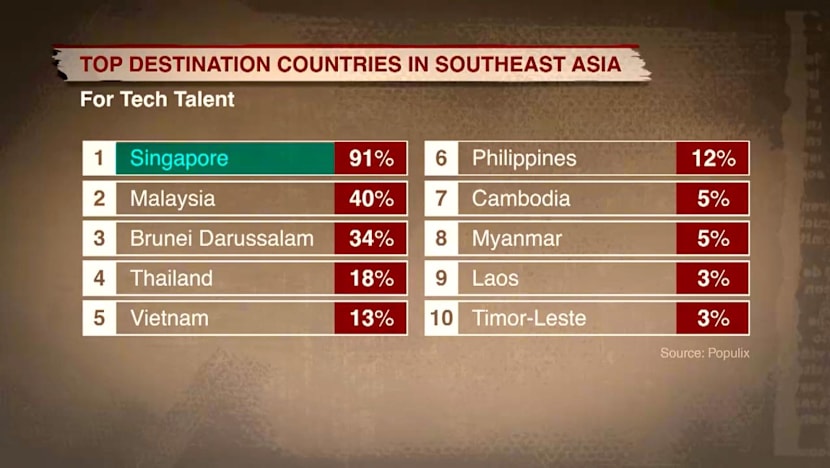

Demand for jobs is shifting towards the digital economy instead. Populix found that jobs in administration, marketing and information technology were the top choices in its survey of young professionals. And the most sought-after destination in Southeast Asia is Singapore.

Indonesia’s tech sector — once a beacon for its young talent — is now faltering. Startup funding plunged by two-thirds last year, reported financial news platform DealStreetAsia.

“(With) a decline in the number of high-skilled people, … our human capital index will stagnate, if not go down,” said Nailul. “This is why global tech companies prefer to invest in Vietnam.”

The impact of a brain drain is being felt in research and academia too.

David Nugroho, an Indonesian academic lecturing at a Thai university, warned: “If smart people — not only the educated ones but also those who are accomplished in their fields — leave the country, Indonesia will end up having people with no qualifications.

“It’ll have an impact on politics, education and the economy.”

The story of returnee scientist Warsito Purwo Taruno offers a glimpse of what is on the line.

Following a successful career developing imaging research used by major oil companies and even the US’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration, he returned home in 2007 and turned his expertise towards cancer therapy.

He developed a helmet to detect brain tumours and a jacket that uses electrostatic waves to hamper the growth of cancer cells. Around 2,000 patients in the last decade, he said, have seen their disease go into remission.

“I’ve found my purpose in life,” the 58-year-old reflected. But it has not been easy.

“The challenges in Indonesia are incredible because everything is unpredictable. Regulations don’t support you, funds and infrastructure are lacking,” he said. “But if we can achieve something and help many people, that’s what really motivates me.”

For every skilled Indonesian like him who returns, however, many others choose to stay abroad.

“There’s a big slogan in the government that we’ll be an advanced economy (by 2045) with … the windfall from (Indonesia’s) demographic dividend,” said Timothy. “(But) the expected progress … doesn’t correspond to the reality.”

DUAL CITIZENSHIP, OTHER SOLUTIONS PROPOSED

The country is not ignoring the brain drain issue. Prabowo upgraded the Indonesian Migrant Workers Protection Agency to a ministry last October, with Abdul Kadir Karding as its minister then, to safeguard Indonesians abroad and prepare those planning to leave.

The ministry offers language and skills training while warning of the dangers of migrating unprepared. “Living in another country isn’t easy,” cautioned Karding. “Prepare yourself as best as possible before going abroad.”

To some, preparing Indonesians for life overseas appears to run counter to the objective of stemming a brain drain. But Karding argued that it could benefit Indonesia in the long run.

“Those who work abroad are actually investing in human resources,” he said. “When they come home, they can become experts. They can start businesses, and I’ve seen many examples of returnees who’ve succeeded in their ventures.”

Others say stronger incentives are needed. One idea being considered is dual citizenship, which is not currently permitted for Indonesian adults.

“It’ll persuade Indonesians living overseas (to) still hold Indonesian nationality,” argued Sulistyawan Wibisono, the president of the Indonesian Diaspora Network Global.

But not everyone is convinced. “People who’ve enjoyed a better quality of life, better public service and so on will be reluctant to come back,” said Nailul.

What Indonesia must do is speed up the revitalisation of many sectors and strengthen job creation, said Maftuchan. Also, authorities must help new graduates and existing workers to reskill and upskill to keep up with a changing economy, he added.

Tackling corruption and the high incremental costs of doing business are equally urgent, experts highlighted.

“There are many investments that run away from Indonesia because there’s no (legal) certainty (in) enforcement,” said Sulistyawan. “Also, the bureaucracy is very complicated, very difficult to deal with.”

Examples on the ground show what is possible when talent stays. Andanu Prasetyo once dreamt of becoming a barista in Australia, inspired by Melbourne’s cafe culture. In 2015, he opened Toko Kopi Tuku in Jakarta’s Cipete district instead.

From a single outlet, the brand has grown to more than 60 stores across Greater Jakarta and several cities, employing more than 1,000 people.

“After experiencing the scene firsthand, I realised what creates an atmosphere isn’t just delicious coffee or sophisticated machines,” said Andanu, 36. “What matters is a good ecosystem.”

Had he left Indonesia, those jobs would have gone with him.

“From what I know, the answer isn’t to run away but to appreciate what’s around us and practise more gratitude. Of course, that’s easier said than done,” he added.

Still, for some others, the pull of life abroad is stronger. Edwin in Bangkok misses his son but has no immediate plans to return to Indonesia.

“Thailand makes me feel at home. I don’t think I can find it in Jakarta,” he said. “From what I’ve read, from the news, social media, Indonesia is losing the opportunity to progress.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.