Philippines’ new military deal with US: Will it tilt power balance in South China Sea?

Filipino fishermen welcome the increased presence of US troops. Others, such as a provincial governor and a woman pressured into sex work in her youth, worry that it could invite trouble. The programme Insight examines what is at stake.

OLONGAPO, Philippines: Alma Bulawan lives in what was once the Philippines’ “sin city”, a place shaped by decades of the United States’ military presence. She opposes a larger US military footprint in her country but knows she belongs to the minority.

“If you ask people on the street, they’re glad the Americans are returning. It means business,” she said. “Only a few, like us, oppose it.”

The city of Olongapo is not far from the US’ former naval base in Subic, which American troops withdrew from in 1992.

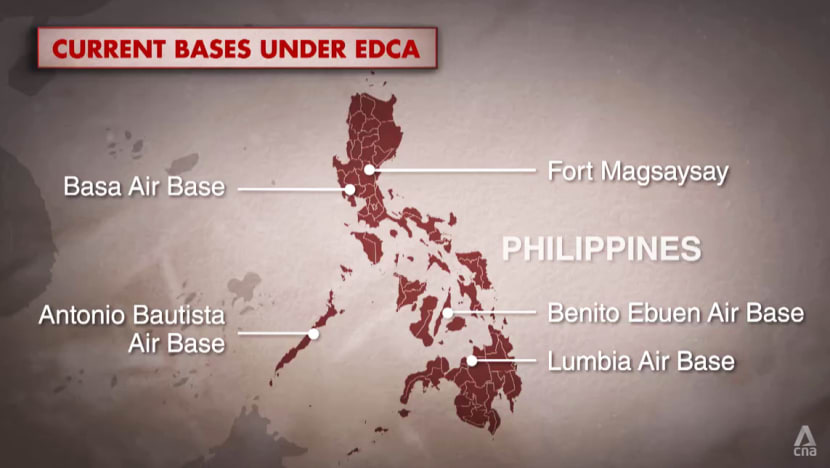

The US’ military presence in the Philippines is now set for its largest expansion since then, after both countries announced in February that the number of bases the US could operate out of will increase from five to nine.

Last month, the locations of the four new bases under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) were announced. Three are on Luzon island, close to Taiwan, and one is in Palawan province, adjacent to the South China Sea.

The expansion comes as Washington steps up its Indo-Pacific influence to counter Beijing.

The most serious flashpoint in the region is Taiwan, which China regards as a breakaway province to be reunified with the mainland and which the US is required, under the Taiwan Relations Act, to provide with arms for its defence.

Beijing’s claims to much of the South China Sea, a major trade route, are also a source of conflict with some Southeast Asian nations whose fishermen have been outmuscled and intimidated by larger Chinese vessels.

The programme Insight examines whether the US and Philippines’ new deal will even out the power imbalance in the South China Sea or drag Filipinos into a superpower rivalry.

‘RAINING MONEY’, BUT CHILDREN WERE ABANDONED

Olongapo residents, more than most, have seen both the shiny and dark sides of American military presence.

Before the troop withdrawal, the city’s seedy bars and nightclubs were making a windfall from off-duty Americans. “It was like raining money,” said present-day pub owner Joel Merza. But there would be riots when they got drunk, added Bulawan.

Forty years ago, Bulawan found work in a bar there. And like the many other young women working in bars, she found herself pressured into sex work.

She got pregnant at the age of 24 and gave birth in 1987 to an Amerasian son. The term refers to children of local women fathered by American soldiers, and these children were stigmatised owing to their illegitimate status.

WATCH: Why I’m against more US troops on Philippine soil — The lessons of ‘Sin City’ (8:06)

“There are many Amerasians who were abandoned,” said Bulawan, who went on to become president of Buklod Centre, a non-profit organisation that helps to change the situation of women in sex work.

“The men would tell (the women), ‘You’re a prostitute, you’re working in a bar. How (can) I (be sure) that’s my child?’”

There are an estimated 50,000 to 250,000 Amerasians in the Philippines, and many grew up in poverty. Despite this, “the view of the community is still that the Americans helped us a lot”, Bulawan said.

When it leased and controlled the Subic naval base — the last of six bases to be returned to the Philippine government — the US provided economic, military and housing assistance to the Philippines.

Related stories:

In the financial year that ended in September 1991, the Philippines received US$408 million (S$546 million) in connection with the bases, and the Subic base had pumped more than US$344 million a year into the Philippine economy, the New York Times reported.

Elsewhere in Zambales province, on the west coast of Luzon, fishermen like Corterio “Boyet” Meer welcome a bigger American presence.

Meer has been fishing for 39 years but has gone only twice to Scarborough Shoal, even though fish are “really abundant” there.

The disputed reef in the South China Sea is within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone but effectively under Chinese control.

“I don’t go there any more because we’ve been prohibited. … There are Chinese guards at Scarborough,” he said. “We’d get scared because they have guns. That’s why we’d rather just go home.”

Although the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague has rejected most of Beijing’s claims to the South China Sea in a case brought by the Philippines, small-scale Southeast Asian fishermen still find their right to fish under threat.

With greater US access to his country’s bases and facilities, “we have protection from those who want to occupy the Philippines”, said fisherman Jeremias Mesia.

“At the very least, (China) will be more careful in the way it treats us,” said Jay Batongbacal, the director of the Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea at the University of the Philippines.

“China is controlling almost the whole region. Our own fisher folk can’t even fish in our own waters because China prevents them from doing so.

“Because of that, we have no choice but to strengthen our security alliance with the US so we can protect our own interests.”

CHINA NOT THE ENEMY?

In northern Luzon’s Cagayan province, however, Governor Manuel Mamba begs to differ. China is “not an enemy”, he said. “We have intermarriages with them. We have good relations with the Chinese.”

During disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic, China rendered help by giving rice, he cited as an example.

Cagayan is home to two of the four new sites the US military can access: Camilo Osias naval base and Cagayan North International Airport, or Lal-lo airport. Mamba worries that this will “invite more enemies” and drive away Chinese investors.

His priority is to reopen Cagayan’s Aparri port for it to be a gateway to Northeast Asia. He sees China as the “biggest market” for his province’s agricultural, fishery and livestock products.

“I’d rather trust this neighbour than somebody who’s far, far away,” he said.

“What I’m saying is, most of the people do not discuss EDCA on the streets here. What the people discuss here is how they’d be able to fill their stomachs every day.”

The rehabilitation of the Aparri port would require dredging the sea floor to allow bigger ships to dock. Part of the Cagayan River Restoration Project, this also aims to mitigate flooding.

In 2020, news outlet The Philippine Star reported that two companies, Riverfront Construction Incorporated and Great River North Consortium, had been accredited for the project and would foot its cost. But controversy has erupted since.

Environmentalists, fishery representatives and Aparri’s mayor have claimed the dredging is a cover for black sand mining, and there is concern that the black sand is being shipped to China, news site Rappler reported in 2021. Extensive extraction of the resource elsewhere in the Philippines has caused coastlines to recede.

In response, Mamba challenged the critics to prove their allegations.

Like him, International Peace Bureau co-president Corazon Fabros disagrees with the “Western narrative that the enemy is China”.

“Who gains in (the) billions of dollars when there’s war? The one who (would make) a killing (from) a situation of war is the US,” she said.

“They sell the arms, they sell all these fighter jets and everything, including what the soldiers will wear.”

Analysts noted, however, that former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte’s pivoting towards China did not ultimately benefit his country’s strategic interests — “particularly in the West Philippine Sea”, cited Aries Arugay, a visiting fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

Because Chinese incursions … not only continued but … intensified, despite the gesture of cordiality being extended by the Duterte administration.”

During much of his term from 2016 to last year, Duterte distanced himself from the US. He even threatened to suspend defence pacts including the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) and the annual Balikatan joint military exercise.

In the final months of his presidency, however, the Philippines and the US held their largest joint military exercise in seven years.

WATCH: Philippines welcomes more US troops at home — Will it be worth it? (47:27)

NOT A ZERO-SUM GAME

Under the current president, Ferdinand Marcos Junior, ties have grown warmer, and he was welcomed to the White House this month by US President Joe Biden.

But Marcos Jr has not turned his back on China, which he visited in January and returned from with US$22.8 billion in investment pledges.

Maximising the benefits from both superpowers will be a “balancing act”, said Batongbacal. “They have an offer, but that always comes at a price.”

There is always apprehension that each time the Philippines “gets closer to the US”, there would be a “corresponding deterioration” in China-Philippine relations, said Arugay.

But other Southeast Asian countries have shown it is possible to manage relationships with both superpowers, he added. “So Philippine foreign policy and strategic policy should be clear that there’s no zero-sum game here.”

When it comes to the EDCA, first signed in 2014, the Philippines has also struck some sort of balance.

It fulfilled its constitutional requirement that bars foreign troops from having a permanent presence in the country, by allowing for the rotation of American forces stationed at its bases.

And it skirted the “very unpopular” notion of having foreign bases in the country, as the sites and facilities remain under Philippine control, Arugay noted.

Fabros’ opposition to the VFA and to the presence of foreign forces in her country stems from the fact that US troops are given “a lot of privileges”, like where they are detained if convicted of a crime and being allowed to remain in US custody while judicial procedures are ongoing.

In 2005, US Marine Lance Corporal Daniel Smith was accused of raping a Filipina and was allowed to be detained at the US embassy while his case was under appeal. Eventually, he was acquitted.

In 2014, another Marine, Lance Corporal Joseph Scott Pemberton, killed a transgender woman. He was pardoned by Duterte in 2020 after serving less than six years of his sentence in an air-conditioned cell at a Philippine military base.

These cases show the “asymmetrical relationship” between the Philippines and the US and can stir negative sentiments, adding to the “historical trauma”, said Arugay.

But Batongbacal reckoned that with smartphones and social media, such incidents “won’t happen easily any more”.

Technology has occasioned a bittersweet ending in one case at least: Last year, Bulawan’s son, Edmark, saw his father for the first time after she used DNA testing to track him down.

“I’m happy for him now, for his future, because we found his father,” she said.

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.