Commentary: What the rise of digital banks means for Singapore's seniors

Singapore is ageing as fast as we are going digital. Are the newly launched digital banks backed by the likes of FairPrice and Singtel ready for our seniors?

Elderly men seen resting outside Raffles Place MRT on Jan 14, 2022. (File photo: CNA/Calvin Oh)

SINGAPORE: Many of us have experienced this especially in the last few years – an older relative needing help with a new digital initiative, be it PayNow, online shopping, figuring out Parking.sg or downloading a mobile app to pay their bills. Sometimes, these conversations lead to frustration between generations; other times, one party gives up on seeing the process through.

The reality is that Singapore is ageing rapidly. There are currently about 678,100 residents aged 65 and above in Singapore, out of a total population of 5.64 million.

By 2030, one in four citizens will be 65 years old and over. In 2050, the silver generation is expected to make up nearly half of Singapore’s population.

This presents a ripe opportunity for silver-tech solutions. It seems that seniors too are getting more digitally savvy – whether by choice, or forced by circumstances.

During the pandemic when physical branch services were disrupted, more seniors took to mobile and Internet banking.

At the peak of the pandemic in March 2020, OCBC reportedly saw a 20 per cent year-on-year growth of digital users aged 60 to 80, compared with a 7 per cent increase in other age groups. At DBS, almost a third of the 100,000 customers who activated their online spending services between February and April 2020 were above 50.

ARE BANKS READY FOR THE OLDER GENERATION?

A wave of new digital banks backed by the likes of Standard Chartered and FairPrice Group and Grab and Singtel were recently launched in Singapore. How will our seniors take to them – and are the banks prepared?

Many of today’s digital solutions are still built with today in mind. In the interest of speed to market and secure users - the younger digital natives are often prioritised in design decisions, from seamless digital onboarding processes to defaulting to chatbots over human assistance. For seniors who lack familiarity with technology, this puts them off embracing the benefits of digital banking.

The pandemic may have accelerated the adoption of digital banking among seniors, but whether this creates sustainable change depends on some fundamental shifts in mindsets.

Today, when it comes to digitalisation, it seems the needs of older persons are seen as added developmental costs and deprioritised deep in the backlog. But as far as accessibility guidelines go, making more inclusive design choices would mean solutions can be more accessible to all users, regardless of age, digital literacy, and the varying physical or cognitive abilities influencing usability for all.

Should you sign up with a digital bank that has no physical branches?

WHY SENIORS ARE THE MOST IMPORTANT GENERATION TO DESIGN FOR

Japan’s super-aged society – nearly 30 per cent of their population is over 65 - offers lessons on how financial institutions are catering to seniors.

In Japan, seniors hold half of the country's US$17 trillion in financial assets, according to Japanese economist Kouhei Komamura. As their population ages, the pile of captive capital held by those with dementia is expected to reach US$2 trillion by 2030, or more than 10 per cent of the nation’s total personal financial assets, Financial Times previously reported.

Similarly in a rapidly ageing society like Singapore, designing for seniors will soon become a business imperative. The costs of not doing so could result in a growing social problem where the (digitally) vulnerable lose their savings due to unfamiliarity with digitalisation and financial fraud.

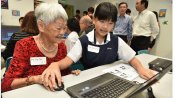

To keep seniors at pace with increasing digitisation, the Singapore Government’s Seniors Go Digital initiative has trained more than 190,000 seniors to live digital lives - from making video calls, accessing Government digital services, to e-payment tools like scanning QR codes. Banks like POSB have also introduced digital ambassador roles at branches to provide guidance on navigating digital-enabled services.

However, even though seniors led digital adoption rates during the early days of the pandemic when the disruption of physical branch services forced them to go online, there is a possibility that resumption of day-to-day activities may lead seniors to revert to old habits and line up at banks again.

Sustaining the momentum of digital adoption among seniors requires an equal focus on retention.MOVING BEYOND SIMPLY ADOPTION TO AN ACTUAL BANKING EXPERIENCE

Yet, identifying the need for higher retention rates in digital banking without actionable steps has no legs. While age-old institutions going online can help create ease, it is a particularly challenging task as it has to deal with a key component linked with it - age-old traditions.

Reframing our mental models could be the answer. While solutions such as increasing font sizes or having bigger buttons, might help, it does not take us to the heart of the issue. Instead, there needs to be a shift towards understanding seniors and their day-to-day needs, which could provide invaluable insights on how to futureproof the system.

We believe three overarching strategies can be applied when seeking inroads towards understanding the silver demographic.

The first is the need for re-learning. Digital services are drivers of self-discovery and self-serve, but for the digitally uninitiated, it represents an unsupported step into the unknown. For seniors, a frictionless experience could easily turn into a slippery slide towards frustrating experiences – such as not being able to get the appropriate help when something goes wrong with their online banking experience.

Having a good learning system when launching a mobile banking service would greatly benefit overall adoption by seniors. Whether it's simply having a clear onboarding and help screens throughout the app, or physical sessions with trained staff members, the objective remains - to remove the fear of learning from users by understanding the style best suited to that particular group of seniors.

The Central Provident Fund (CPF) does this by providing a customer helpdesk that users can call to interact with and clarify their doubts - providing a parallel track towards learning. Users are still encouraged to be digital, but they have the option of getting help from another person.

MEETING IN THE MIDDLE

The second approach would be to reframe where banking touches the lives of seniors. Seniors have been through the decades predating the technological revolution of the 80s, leading to a starkly different approach to their adoption of tech.

When creating a banking service, shifting focus to the highly nuanced lives of seniors and their daily behaviours is essential. For instance, identifying how seniors interact with branch managers and the most common services they seek can inform how an app might better meet their needs.

This could also lead to the inception of in-branch spaces specifically for seniors to learn, and provide supplementary support such as Wi-Fi for them to download the banking app or approach a staff to walk through the latest app features and its relevance to them.

BUILD UP, NOT DOWN

The final approach involves returning to the key tenet of design thinking - harnessing the human-centric concept of “relevance”. As touched on earlier, a substantial portion of the senior demographic became digitally active during the pandemic. That said, the apps used by these groups were not particularly built to be senior-centric.

What this means is when thinking about building a banking app, its purpose needs to be tested by asking “how and why would seniors use it”.

The insights from such an approach can then lead to nuances that can improve the senior’s journey, such as how a simple “push-to-call” button might drastically improve their on-app experience.

India’s Bank of Baroda has a digital banking platform designed specifically for the elderly, focusing on key services that seniors use, along with easy support, such as a voice-based search service on the dashboard.

Prism, a bill management app, is another example. Aside from consolidating bills and sending payment notices, it has a function to remind users on upcoming bills to help them avoid forgetting an upcoming payment and overspending.

What both these apps demonstrate is clear - the design clearly shifts beyond simply being digital. They interweave digital solutions with daily user routines to ensure users are not stranded, regardless of their tech literacy level.

Understanding how to approach teaching and adoption of something as fundamental as banking for the senior demographic can be tricky.

Seniors work in ways that are markedly different from what we generally assume, often leading to generalisations that underserve or overwhelm them. Yet, contrary to popular belief, catering for the elderly does not mean subverting ingenuity. Instead, it should be viewed as a good approach towards investing in the future of digital banking, today.

Anna Shin is a senior experience strategist and Mark Lim is a UX writer at R/GA Singapore, a global digital product, marketing and brand innovation company.