Commentary: My handwriting is terrible. Does it really matter?

Years of typing and texting have taken their toll. But studies show that we learn and remember more when we write by hand, says the Financial Times’ Pilita Clark.

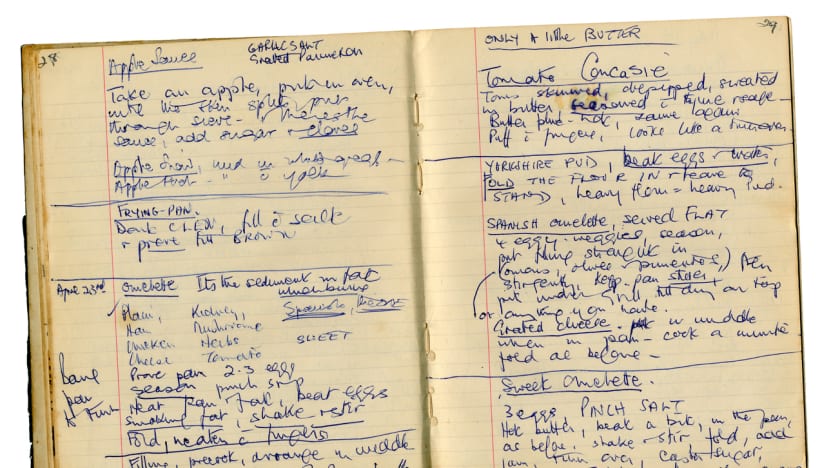

File photo of pages from an old handwritten cookery book. (Photo: iStock/whitemay)

LONDON: Last month, I went on holiday to a small town at the bottom of Spain that I have been visiting for more than 20 years, where a friend asked: “Why is your Spanish still so bad?”

“Er,” I said, struggling to remember how to say in Spanish that, after decades of fitful studies, there had in fact been times when I could speak as well as any local four-year-old.

This was not one of those times, unfortunately. So I went home, sat down and started writing out lists of verb conjugations by hand, which was when I discovered something worse.

My handwriting, never good, had turned into barely legible scrawl. My words jerked across the page like the trails of a snail dunked in crystal meth. The very act of writing was a strain. Years of typing and texting had taken an unattractive toll.

I cannot be alone. Nearly 60 per cent of Britons say they write less by hand than they did five years ago, a survey found last year, and 12 per cent have never written even a shopping list. Children email Santa and some struggle to hold a pen.

Related:

The question is, does this really matter? Wouldn’t the world be a better place if everything we wrote was as clear and unambiguous as the printed word? The medical world certainly would: A 42-year-old American once died after a pharmacist reading a cardiologist’s sloppily written prescription dispensed the wrong pills.

But the data show that, when it comes to learning, handwriting definitely matters. Several studies have found that both children and adults learn and remember more when they write by hand. “It stimulates the brain in a very different way than a keyboard does,” said Audrey van der Meer, a neuropsychology professor in Norway whose research on the topic is widely cited.

This casts a depressing light on recent figures suggesting that the share of younger UK primary school pupils reaching expected writing standards sank from 70 per cent in the pre-pandemic year of 2019 to 59 per cent in 2022.

Van der Meer admits she hardly writes by hand any more and recently realised she would not recognise her 19-year-old daughter’s writing, “because as far as I can tell, she has hardly ever written anything by hand”.

When van der Meer gives lectures, she stares out at “a wall of Apple signs” on the laptops of her students, few of whom take notes by hand now. “It’s a real shame,” she said.

The withered state of writing has begun to affect other lives too, like those of courtroom handwriting experts. “It’s a concern,” said Steve Cosslett, a British forensic document examiner who has given evidence in hundreds of court cases since he began his career at a Home Office forensic science laboratory in 1983.

For example, to check the authenticity of a signature on a will, you need a number of genuine signatures by the writer. But these are harder to find now that people do not sign things like cheques any more. “People can’t provide sufficient reference material,” he said.

Cosslett also reckons the forensic handwriting field is shrinking. The number of forensic document analysts working for laboratories accredited to do police work in England and Wales has shrunk from at least 25 in the 1980s to five or six today, he said.

That is unsettling, considering some of the cases on which Cosslett’s firm has worked. His analysis helped convict Victorino Chua, a nurse in north-west England who was jailed for at least 35 years in 2015 for murdering and poisoning patients by injecting insulin into saline bags. And Cosslett’s colleagues’ evidence was used in the case of a carer who was put away for nearly as long after she forged the will of a reclusive millionaire before starving him to death.

It is hard to imagine a world in which handwriting dies out completely, let alone a time when everyone prefers to type out a love letter or dictate it to Siri. I think something will also be lost if there are no more people like graphologist Tracey Trussell.

Graphologists, unlike most forensic handwriting experts, analyse handwriting to assess personality traits. Sceptics abound about this sort of thing, but Trussell said she is often hired by companies – hotels, property managers, engineering firms – to assess potential employees.

“Business is as brisk as it’s always been,” she assured me the other day. Curious, I asked if she would analyse a bit of my handwriting and, within a day, had received her eight-page evaluation of my scrawl.

I was told my “self-esteem is healthy” on account of my personal pronoun “I” being a good size, while my right-slanted words show a finely tuned emotional barometer, albeit with “the ability to be acerbic and scathing at times”.

“Spot on,” said my husband. The rest of us may take more convincing, yet life would surely be poorer without this sort of thing. As Trussell notes in her book, Life Lines, writing by hand is one of our species’ foundational achievements. We take it for granted, but if it disappeared completely, we would miss it more than we can ever imagine.