Commentary: Harvard may recover, but the trust is gone

The Trump administration’s standoff with Harvard has shaken long-standing assumptions about the reliability of US universities, raising questions about where Singapore and Asia will educate their next generation of leaders, says SUSS’ Ben Chester Cheong.

Tour groups walk at Harvard University on Apr 17, 2025 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. (Photo: Sophie Park/Getty Images/AFP)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: When the Trump administration escalated its standoff with Harvard University, revoking its ability to enrol new international students, even ordering thousands of current foreign students to transfer or leave the United States, fear and confusion spread rapidly.

Now, after an intense backlash and a lawsuit by Harvard, the Trump's administration’s plan to bar foreign students at Harvard has been blocked. For now.

A judge has issued a temporary restraining order, pending a set of hearings this week.

Some observers caution that the Harvard ban might prove to be a temporary tempest - a politically motivated stunt that could be reversed with time. After all, the US has seen abrupt policy shocks before that were later softened (think of the trade tariffs on allies and rivals alike).

Could the Harvard saga be another such episode? Possibly. But the damage may already be done. While the intensity of the storm could potentially ease, the days of unfettered US-Asia academic exchange may not fully return to the old normal.

Singapore and its neighbours must therefore prepare for a world where American universities are a less automatic choice and where Asia needs more self-reliance in training top talent.

FUTURE LEADERS LEFT IN LIMBO

It’s undeniable that the Trump administration’s clampdown, targeting a crown jewel of American higher education, marks an alarming escalation of politics intruding into academia.

The Trump administration has justified this unprecedented move by accusing Harvard of “fostering violence” and “antisemitism” and even of ties to China's Communist Party.

The university in its lawsuit blasted the action as "unlawful" retaliation for its rejection of "the government's demands to control Harvard's governance, curriculum and the 'ideology' of its faculty and students".

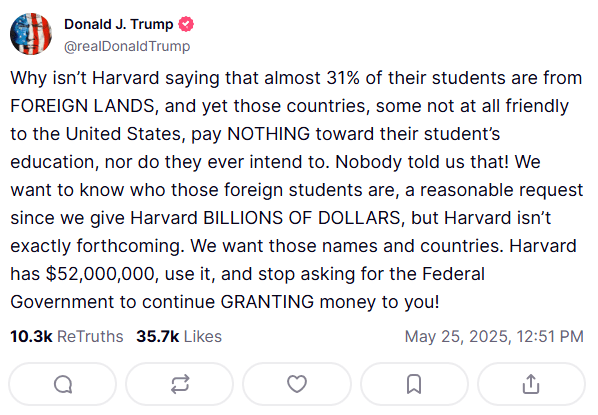

On Sunday (May 25), US President Donald Trump defended the ban, saying that the home countries of some of Harvard's international students are "not at all friendly to the United States".

“We want to know who those foreign students are, a reasonable request since we give Harvard BILLIONS OF DOLLARS, but Harvard isn’t exactly forthcoming. We want those names and countries,” he said in a post on Truth Social.

Why does this matter to Singapore and Asia? Because for decades, an acceptance letter from a top US university was a ticket to unparalleled learning and networks.

US institutions, particularly Harvard, have helped shape generations of ministers, diplomats and civil servants from Asia and beyond. For instance, Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong holds a master’s in public administration from the Harvard Kennedy School. Meanwhile, Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong and recently retired ministers Heng Swee Keat and Teo Chee Hean are also Harvard alumni.

About 6,800 international students - including 151 Singaporeans - are enrolled at Harvard in its current academic year, accounting for 27 per cent of the student body, according to university figures.

If Harvard, which has produced eight US presidents and is arguably the most prestigious of all the Ivy League schools, is off limits, many Asian elites may rethink going to the US at all. They may question if it’s worth investing in an American education if the welcome can be rescinded on a whim.

Indeed, US officials have warned that other universities could face similar bans. “This should be a warning to every other university to get your act together,” Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Kristi Noem said last week.

For Singapore, this has tangible implications. The country sends thousands of students to US universities annually. Many are on government scholarships or self-funded with hopes that an Ivy League pedigree will vault them into leadership tracks.

If those plans are now in doubt, Singapore’s public sector talent pipeline may need to adjust.

We could see more Singaporean scholars head to the United Kingdom, Europe or Australia instead, or remain at home for education.

AN OPPORTUNITY FOR SINGAPORE UNIVERSITIES?

Asia’s rise over the past decades has in part been fuelled by sending its best students westward; that option now comes with caveats. Singapore and its neighbours must therefore invest even more in developing regional centres of excellence.

This is already happening. China has poured resources into its C9 League universities, India is seeking to reform its higher education, and Singapore and South Korea boast some of the finest schools in the world. The trend can accelerate, spurred by necessity.

As global education becomes collateral in larger political fights, Singapore could emerge as a neutral academic waypoint.

The city has long punched above its weight in education. Its universities are world-class. Education here is not subject to partisan reversals. Institutions can plan across decades, not election cycles.

The outcome of the recent general election reinforces this stability.

With geopolitical tensions rising and US-China ties under strain, Singapore’s non-aligned stance and multicultural fabric make it an ideal meeting ground for scholars of all stripes.

We already see this in initiatives like the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, which was established in collaboration with Harvard but has come into its own as a training ground for future leaders from over 90 countries. Its faculty is ranked among the top 2 per cent of the world's scientists.

A TIME TO LEAD BY EXAMPLE

The education of international students has been America’s “greatest soft power resource”, a term coined by Professor Joseph Nye of Harvard University, because when those students spend formative years immersed in American ideals and later become leaders back home, they naturally help align their countries’ outlooks with the US.

The Harvard ban will have consequences that outlast the current political theatre. Yet, as with previous storms, this too shall pass - if not fully, then partially. Policies can change, doors can reopen.

But rather than passively waiting, Singapore and Asia can turn this moment into an impetus for growth. We can redouble efforts to nurture talent at home and within the region, creating an ecosystem that is resilient to external shocks.

Ben Chester Cheong is a law lecturer at the Singapore University of Social Sciences, and of counsel at RHTLaw Asia. He is a visiting fellow in law at the University of Reading, and a centre researcher at the University of Cambridge.