Commentary: Could Anwar’s government bring back Kuala Lumpur-Singapore HSR project?

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim may have criticised the previous government’s decision to terminate the high-speed rail project, but he probably won’t bring it back, says National University Singapore’s Serina Rahman.

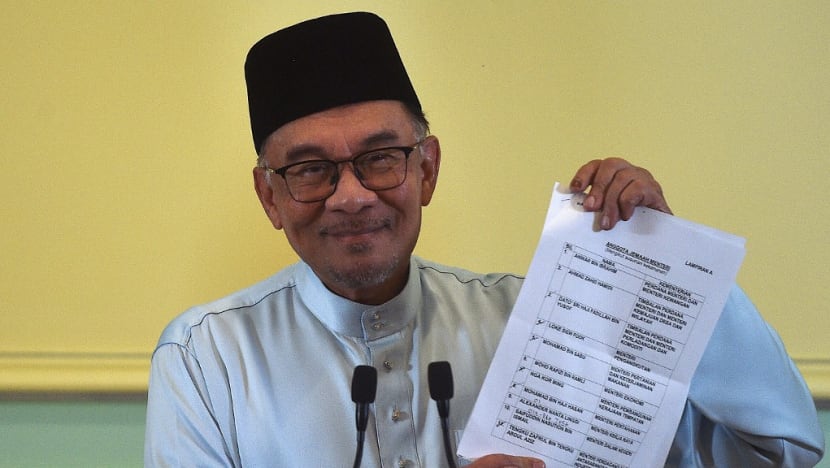

Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim holds a document during a press conference to announce new Cabinet members at the Prime Minister’s Office in Putrajaya on Dec 2, 2022. (Photo: AFP/Arif Kartono)

JOHOR BAHRU: Malaysia’s new Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has assembled his Cabinet, appointing himself as the finance minister. And one of the most pressing tasks under his double portfolio will be to revise and pass the 2023 budget.

Anwar has said his primary focus would be on the economy and the rising cost of living, reflected also in the tweaking of the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs to the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Cost of Living. With infrastructure development a clear way of boosting growth and supporting jobs, could this mark the revival of the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High-Speed Rail (HSR) project?

The HSR project was once an opportunity to showcase Malaysia’s cutting-edge transportation technology, as well as champion local development along its route.

With the fall of the Barisan Nasional government in 2018, the project was put on hold by then prime minister Mahathir Mohamed on the grounds of Malaysia’s economic difficulties.

As the world ground to a halt under COVID-19, the project was finally terminated at the end of 2020, with Malaysia paying Singapore S$102.8 million in compensation for costs incurred.

By end-2021, then prime minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob suggested reviving discussions on the HSR, even saying in August that he would like to see the HSR revived at the earliest opportunity - albeit with some route changes and the possibility of extending it northwards to Thailand and China.

KL-SINGAPORE HSR REVIVAL UNDER ANWAR?

Could Anwar’s government bring back the HSR? In a statement in January 2021, Anwar called the cancellation a mistake “both from a current economic standpoint and in terms of future benefits”, pointing out the economic opportunities it could have opened up, in drawing tourists, businesses and foreign direct investment.

The main reason for cancellation had been Malaysia’s refusal to accept a jointly tendered asset management company. The government at the time wanted Malaysia to make all decisions about its portion of the HSR – about 95 per cent of the track - implying that it did not want Singapore to have a hand in matters on their territory.

Anwar said that this company would have brought technical expertise that both countries lacked, enabled local companies to learn and benefit from the knowledge transfer and ensure transparency.

There had also been some discussion of reviving it to run only between Kuala Lumpur and Johor Bahru, but the idea received much derision. Anwar had criticised it as a move to “throw good money after bad” and a domestic HSR would be a “white elephant”.

There is already the KTM Electric Train Service (ETS), a medium-speed electrified double-track railway, between northernmost state Perlis and Negeri Sembilan. The Gemas-Johor Bahru stretch is expected to be completed in mid-2023 and would connect Johor Bahru to Kuala Lumpur in about three and a half hours.

DON’T GET HOPES UP FOR HIGH-SPEED RAIL

While some may feel that this justifies the need for a HSR that will cut travel time down to only 90 minutes, there is the matter of costs and the expected (high) ticket prices in this time of widespread financial struggle.

Corporate travellers may prefer to pay a little more to travel by plane, and some flight tickets might actually be cheaper with budget flights. Express buses between Johor Bahru and Kuala Lumpur usually take about four hours and are the most economic choice for those without cars.

Rail travel is not known to be an instinctive travel option in Malaysia and Singapore. While this might be the result of a lack of passenger train options, it remains to be seen whether train travel can be as economically viable or accessible to the average person as the projections promise.

Furthermore, the HSR was a Barisan Nasional initative. Many also blamed the previous Pakatan Harapan government for its failure, though Mahathir’s administration has always maintained that it was only to reduce costs given the state of Malaysia’s economy.

With Anwar’s clear focus on reducing inflation and the cost of living for the masses, as well as visible intentions to ensure development and infrastructural improvements in East Malaysia and Perak (given the number of seats given to parliamentarians from these states in his new Cabinet), it is highly unlikely that a luxury transport option such as the HSR will be on the priority list.

At the local level, while regions along the planned HSR train route, and especially the stations, welcomed the opportunity for development and business, little heed was paid to those who would lose their homes and land to forced requisition for the train tracks.

Not long before the project was put on hold, local communities along the route were reeling from the knowledge that parts of their land were suddenly going to be frozen for the project, with information on compensation still unclear. For them, the unexpected cancellation of the HSR was a relief.

BETTER RAIL OPTIONS FOR JOHOR, KUALA LUMPUR

Instead of the HSR, the almost 1 million Malaysians working in Singapore are looking forward to the Johor Bahru – Singapore Rapid Transit System (RTS) railway link instead, to alleviate some of the daily commuter crush at the Causeway and Second Link.

With economic opportunities in Singapore seen as far more lucrative than in Kuala Lumpur, the transport demand lies in the opposite direction. The RTS project is moving along swiftly, with projected completion and operation in 2027.

The short-lived 2023 budget tabled by the previous Barisan Nasional government included allocations for the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), intended to connect the more developed west coast to the less developed east coast, and the Mass Rapid Transit 3 (MRT3) stretch in the Kuala Lumpur urban rail network. No mention was made of the HSR in the budget.

The Johor Bahru RTS, the ECRL and the MRT3 are more likely to help spur economic growth and provide better transport options to more Malaysians.

Far better would be for Anwar’s government to focus on these ways of boosting the economy first, which were already in the 12th Malaysia Plan approved in parliament in 2021 with no objection from his coalition. Federal support for in-state light rail networks would also be a boon to citizens and help support state economies.

With Anthony Loke reinstated as Transport Minister, it looks likely that projects that were mooted under the short PH government reign will be revived. But it seems a safer bet to not get any hopes up for the HSR in the immediate future.

Serina Rahman is a Lecturer at the Southeast Asian Studies Department at the National University of Singapore, and an Associate Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.