Commentary: Why does Malaysia want to make Malay an official ASEAN language?

Malaysia has again proposed making Malay a working language of ASEAN, but this proposal is likely to be a non-starter as ASEAN wrestles with more pressing crises, says a researcher.

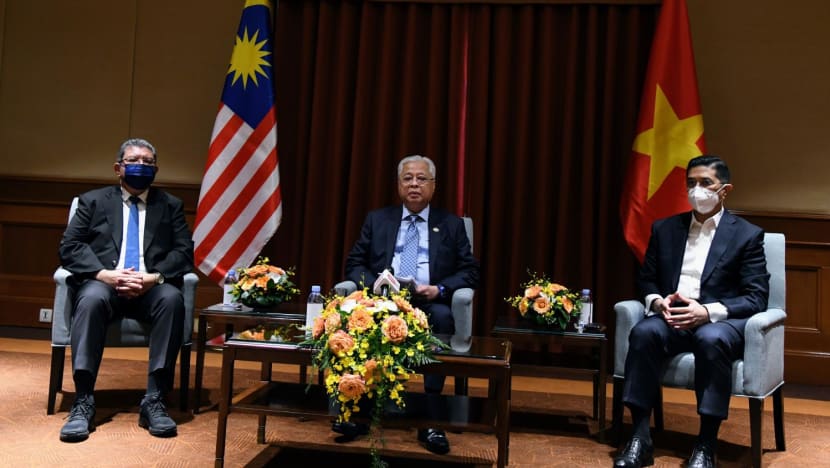

SINGAPORE: Malaysia is at it again. Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob has recently proposed making Malay or Bahasa Melayu the second language of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to “elevate Malaysia’s national language (to) the international level”.

This is not the first instance that Malaysia has proposed using Bahasa Melayu as an official language in ASEAN. Former prime minister Najib Razak made a similar proposal in 2017, but no ASEAN-wide agreement resulted, as other member states clearly did not share the same aspirations.

Learning from that earlier attempt, perhaps, Ismail Sabri now uses the term “second language”, making this revived proposal more palatable than Najib’s earlier suggestion to adopt Bahasa Malay as the “main language” of ASEAN.

Framing it as a “second language” means that Malaysia hopes to promote Malay as the supplementary working language of ASEAN but not to replace English altogether.

PROMOTING THE LANGUAGE OR PUSHING ITS INFLUENCE?

The Malay language is already used widely in ASEAN, as the official language of Indonesia, Brunei, Singapore and Malaysia, and a lingua franca spoken by communities in southern Thailand, southern Philippines and parts of Myanmar and Cambodia.

Given this situation, Ismail Sabri believes that “there is no reason why we cannot make Malay one of the official languages of ASEAN”, and plans to discuss this matter with other ASEAN leaders and to seek support from the Malay-speaking countries.

Despite Malaysia’s persistence, however, the regional bloc will likely view this as another nationalistic endeavour by Kuala Lumpur or even Ismail Sabri himself to score points on the domestic front.

The ASEAN bureaucracy understands well that in a diverse region like Southeast Asia, promoting the dominance of any race, culture or language will not only tilt the balance of the entire organisation, but possibly also erode 55 years of multilateral efforts to preserve regional stability and order.

It is worth noting that English has remained the de facto language of ASEAN since its founding in 1967. This was codified as article 34 of the ASEAN Charter, which states that the “working language of ASEAN shall be English”.

This was not an accidental choice but a logical one, considering the need for a level playing field for all ASEAN members without reifying a particular national language of any single or group of member states, as choosing Malay would have done.

Using English as its official language also underscores ASEAN’s identity as an outward-looking regional organisation and facilitates its cooperation with external partners and other international organisations.

In the unlikely event that ASEAN decides to entertain Malaysia’s proposal, it might open the way for a proliferation of similar requests to pour through the floodgates.

When ASEAN expanded its membership to countries in mainland Southeast Asia in the 1990s, political office holders from those new member states opted to speak in their national language instead of English at formal ASEAN meetings.

MALAYSIA AND ASEAN HAVE FAR BIGGER PROBLEMS

Though currently seeming to support Ismail Sabri’s call, Indonesia may, in the future, request for Bahasa Indonesia to be used in ASEAN. Linguistically, Bahasa Indonesia is a different (albeit closely related) variant of the Malay language, and moreover, the ASEAN Secretariat is in Jakarta.

There were earlier proposals or attempts to promote Indonesian as an ASEAN language, most recently in 2020. As early as 1987, Malaysia and Indonesia had jointly proposed that either Bahasa Melayu or Bahasa Indonesia be used as ASEAN’s official language.

It is unlikely that the already overstretched regional bloc will be able to afford additional human and financial resources for the interpretation and translation requirements arising from any decision to add Malay as an official ASEAN language, much less adopt all the other major regional languages as official ones.

However high a hope Ismail Sabri has for Malay’s regional reach, his aspiration will certainly be relegated to the backburner. ASEAN’s plate is currently full with calibrating the ongoing ASEAN response to the worsening Myanmar crisis and dealing with the broader implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Much more urgent issues, like the South China Sea dispute, will suppress ASEAN’s appetite for another potentially contentious issue such as language politics. ASEAN’s unity has been severely tested in recent years, and it is unlikely to engage in non-pressing issues that will cause further division.

Malaysia has an important role to play in charting the future direction of ASEAN, as it is leading the High-Level Task Force on the ASEAN Community’s Post-2025 Vision.

Kuala Lumpur’s energies could be better vested in its leadership role to strengthen ASEAN’s capacity and institutional effectiveness, as well as to streamline its bureaucratic processes, rather than pushing for a proposal that will likely cause its ASEAN neighbours to say, “Malay tak boleh”.

Joanne Lin is the Lead Researcher in political-security affairs at the ASEAN Studies Centre, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. This commentary first appeared on ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute's blog The Fulcrum.