Commentary: Sabah state election sends a clear message to KL – it’s time for a reset

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has a Borneo-shaped vulnerability right now, says Asian studies professor James Chin.

Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS) supporters waving party flags during a campaign rally in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

HOBART: There was little nuance in the results of Sabah’s 17th state election on Saturday (Nov 29). Sabahans did not mince words: They want homegrown leaders who understand Borneo, not outsiders from the corridors of Putrajaya.

This outcome signals a profound reset in federal-state relations, one that demands introspection by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s unity government.

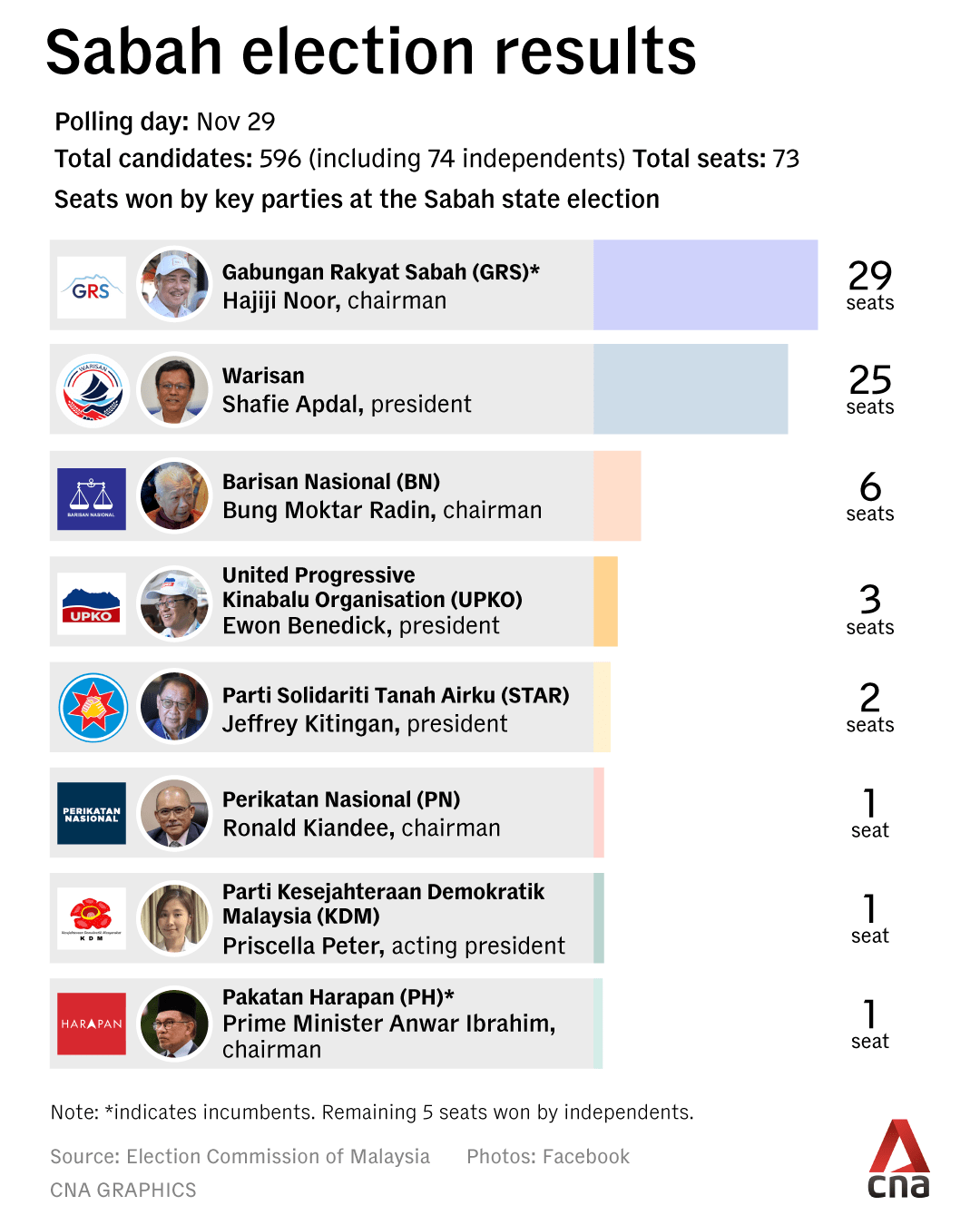

Though none won a simple majority of 37 seats to form the state government, local parties headquartered in Sabah accounted for 65 of the 73 contested Legislative Assembly seats.

The incumbent Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS) coalition secured 29 seats, emerging as the largest bloc. Its rival Parti Warisan Sabah (Warisan) clinched 25 seats. Smaller local parties collectively won six, while five seats went to local independents.

It is an overwhelming endorsement of Sabah-rooted politics, and a crystal-clear rejection of political dominance from Kuala Lumpur.

PENINSULAR PARTIES NOT WANTED

Despite massive resources, the national coalitions – Pakatan Harapan (PH) and Barisan Nasional (BN) that form the federal government and main opposition Perikatan Nasional (PN) – won just eight seats among them, a remarkable decrease from their collective 33 seats at the last state election in 2020.

The starkest sign was the total annihilation of the Democratic Alliance Party (DAP), PH's urban Chinese powerhouse with deep historical ties to Sabah dating back decades. In 2020, DAP had swept six of seven contests.

Contesting eight seats this time, DAP lost every one, even high-profile incumbents such as a state minister, a deputy federal minister and two sitting Members of Parliament. It was shut out by Warisan, which capitalised on anti-federal sentiment in urban strongholds like Kota Kinabalu and Sandakan.

Another clear rejection was of opposition coalition PN, which fielded 42 candidates and won only one seat.

“SABAH FOR SABAHANS”

The campaign had been awash with "Sabah for Sabahans" and “Save Sabah” rhetoric, with local parties framing the poll as a choice between being ruled by locals or by the peninsula.

This divide was ironically reinforced by Mr Anwar himself. In a historical ruling in October, a high court ruled that the federal government had failed to honour Sabah’s entitlement under the Malaysia Agreement 1963 (MA63) to get back 40 per cent of the federal revenue it contributes to annually, and must pay this amount, including arrears dating back to 1974.

Less than three weeks before the Sabah state election, Mr Anwar’s government said it will not appeal the verdict but will appeal the language used in the judgment.

To Sabahans, this was doublespeak and a betrayal. This ruling, meant to restore historical justice, likely fuelled the local sweep.

This rise of Sabah nationalism is no anomaly; it mirrors the rise of state nationalism in neighbouring Sarawak. In the 2021 Sarawak state election, Sarawak-based parties swept 80 of 82 seats. The driving narratives were similar: autonomy from federal government and Sarawak for Sarawakians.

The primary catalyst for the rise is festering historical grievances over MA63. Signed in 1963 as the blueprint for Malaysia's formation, MA63 promised Sabah and Sarawak a significant amount of political and economic autonomy. Yet, for six decades, the Borneo states have felt shortchanged.

Sabah, despite producing about 40 per cent of Malaysia's crude oil, receives a pittance of 5 per cent royalty. Sabah consistently ranks as one of Malaysia’s poorest states, with eight districts in Sabah ranked among the 10 poorest in the entire federation. In 2023, Sabah's gross domestic product per capita was about RM31,000, lagging well behind RM56,000 nationally.

NEW FEDERAL-STATE PARADIGM

What, then, do the Sabah results mean for federal-state relations? It heralds a new era where Putrajaya can no longer take Sabah and Sarawak for granted.

The next general election, expected to be held in 2027, will likely see local parties dominating the Borneo polls. Mr Anwar will need the Borneo Bloc (Gabungan Parti Sarawak, GRS and Warisan) if he wants to stay in power and provide political stability in Malaysia.

This vulnerability should jolt Kuala Lumpur into a comprehensive relook at federalism. The current model, skewed toward centralisation since the 1970s under the strong Mahathir era, has bred resentment.

Embodying the true spirit of MA63 – granting Sabah and Sarawak the autonomy envisioned by founders like Tunku Abdul Rahman and Donald Stephens in 1963 – will require actionable restitution.

Mr Anwar could start by dropping the appeal related to Sabah’s revenue claim. Honouring the court ruling would channel billions back to Sabah and address chronic underinvestment, for the state to improve basic infrastructure like rural electrification and water supply.

Structural reforms must be considered, such as enhanced fiscal transfers and joint resource councils. Acknowledging how Sabahans and Sarawakians feel politically and economically marginalised over 60 years will also help.

EQUITABLE PARTNERS

Equally vital, for the federal government, is to refrain from exporting peninsular political culture to East Malaysia.

Peninsular-style identity politics – framed around race and Islam – clash with Borneo, which has long embodied the multiracial and multireligious harmony Malaysia aspires to. Muslims, Christians and Malaysians of other faiths coexist without the same binary tensions as on the peninsula.

This is also an opportunity to restore veto powers to Borneo. Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore together held a one-third share in the Dewan Rakyat (Parliament) when Malaysia was formed, but Singapore's 15 parliamentary seats were not distributed to Borneo after expulsion in 1965. This rebalance would ensure equitable veto power on amendments, affirming their status as federation founders.

Most crucially, the peninsular political class should learn to see the robust Sabah-Sarawak identity not as a threat but a fortification of Malaysian unity. It is a counterweight to ethnic silos. Sabahans and Sarawakians are proudly both locals and Malaysians.

Mr Anwar, with his reformist credentials, is uniquely positioned to shift the mindset of political elites: His Madani vision of inclusivity rings hollow without this pivot.

Sabah's 2025 electoral outcome is a clarion call for a reset of federal-state relations. Sabah has spoken – Putrajaya must listen or risk the federation fraying.

James Chin is Professor of Asian Studies, University of Tasmania, and Senior Research Associate, Tun Tan Cheng Lock Institute of Social Studies, Malaysia.