Commentary: High-scoring PSLE students may struggle with imposter syndrome later in life

Pegging young learners for greatness can inflict them with a lingering sense of inadequacy that follows into adulthood, says parent and former journalist Debbie Yong.

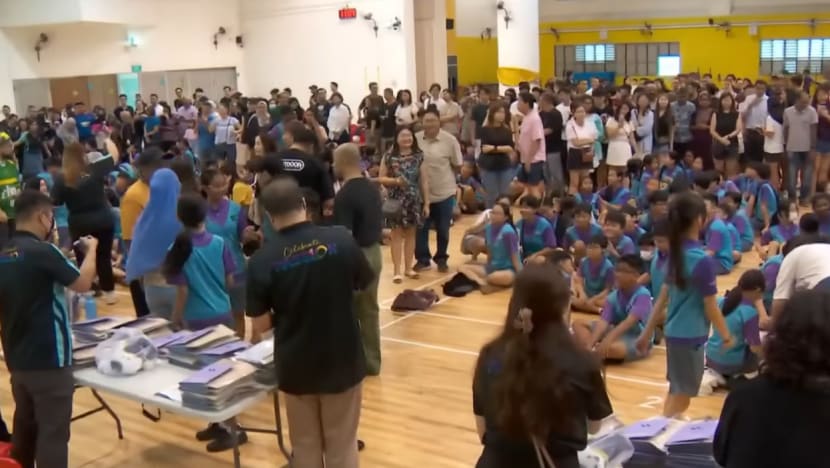

We must emphasise to children that the PSLE is not a predictor of success in life. (Screengrab: CNA)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Following the release of Singapore’s Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) results, parents of students who achieved stellar scores are no doubt filled with pride and excitement.

However, the unspoken expectations that follow a child’s academic success are often overlooked. For high-performing children, being placed on a pedestal at a young age can take a psychological toll.

I was one of those children. Through my own journey - and conversations with high-achieving peers - I’ve realised that we, as parents and society, need to be mindful that pegging young learners for greatness can inflict them with a lingering sense of inadequacy that follows into adulthood.

INTENSE PRESSURE TO PERFORM

High expectations, whether from demanding "tiger parents" or well-meaning teachers, create intense pressure to perform. When applied at such a formative age, this pressure can evolve into imposter syndrome and perfectionism, with individuals setting unattainable standards for themselves.

First observed by psychologists Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes in the 1970s, imposter syndrome is a phenomenon where high achievers don't internalise their own success.

Despite attending the best schools, excelling in standardised testing and earning exceptional grades, those with imposter syndrome don’t feel like they deserve their achievements. As a result, they work harder than needed to overcome their self-perceived inadequacies, and are likely to experience depression and psychological distress.

We see this playing out in Singapore, with worrying implications. According to a PISA study, 76 per cent of Singaporean students feel anxious about exams even when they are well-prepared, compared to the OECD average of 55 per cent.

One in 10 teenagers in Singapore suffers from at least one mental health disorder, according to a study by the National University of Singapore (NUS). Suicide has been the leading cause of death among youth aged 10 to 29 for the last five years.

The constant stress of striving for perfection, coupled with the ever-present fear of failure, can lead to unhealthy coping mechanisms. As a youth, I’ve seen many of my top PSLE-scoring, high-achieving peers struggle with depression, self-harm, and other mental health issues that we didn’t have the language for back then.

Furthermore, the pressure to overwork, at the expense of personal time, often isolates them, resulting in loneliness and the inability to seek help before they reach breaking point. I’ve had friends drop out of school, and lost a good friend to suicide just before the A-level exams.

TOLL ON MENTAL HEALTH

It’s not just about academic performance. As adults, many of my high-achieving peers are now in therapy to cope with the constant need to over-deliver. They’re nagged by feelings of inadequacy despite being high-fliers at work.

A study of over 900,000 adults in Sweden found that top-performing students are four times more likely to develop mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder in adulthood than those who achieved average grades

The problem is, there’s little empathy for high achievers. After all, how many can sympathise with someone upset about scoring an A- or a 99 out of 100?

High achievers often don’t speak out about this for fear of showing vulnerability in the hyper-competitive environments we grew up in. As a result, society doesn’t see the silent struggle of constantly trying to prove yourself at the top, nor the anxiety about failing to meet expectations.

The Ministry of Education deserves recognition for acknowledging this issue and taking steps to address it. The revamp of the Gifted Education Programme and the introduction of full subject-based banding will allow students to personalise their learning experience by choosing subjects at varying difficulty levels that align with their strengths and interests.

In addition, the elimination of mid-year exams in primary and secondary schools will shift the focus from rote memorisation to a deeper understanding of subjects, helping to reduce stress.

Education Minister Chan Chun Sing has also been vocal about the need to redefine success beyond merely achieving high scores to cultivating skills for lifelong learning and adaptability.

PARENTS MUST SHIFT THEIR MINDSETS

However, these changes will have limited effect if we, as parents, do not also shift our mindsets.

Ultimately, we must emphasise to our children that the PSLE is not a predictor of success in life. Their potential is not defined by a test score, but by their curiosity, resilience, and ability to navigate setbacks - qualities that exams don’t measure.

How you respond to your child’s scores matters. If your child didn’t do well, he or she should be supported. But if your child did well, be just as mindful of how you praise and reinforce that success. The expectations placed on high achievers can become a burden that follows them far beyond their school years.

Parents, teachers and mentors must recognise that the pressure on high performers - when internalised and tied to their self-esteem - can be just as damaging as the struggles of students who underperform.

As we continue to normalise discussions about mental health in our society, let’s also unpack the hidden pressures of success and create space for conversations around the well-being of high-performing students.

It’s time to recognise that success doesn’t have to come with an unspoken weight, and that being “enough” doesn’t mean being at the top.

Debbie Yong is a former journalist turned brand strategist and a mother of two.