Commentary: Are we getting desensitised to scams even as fraudsters get more innovative?

The proposed shared responsibility framework is significant as it represents a first venture into compensatory measures to alleviate the hardship suffered by scam victims, says Rajah & Tann’s Jansen Chow.

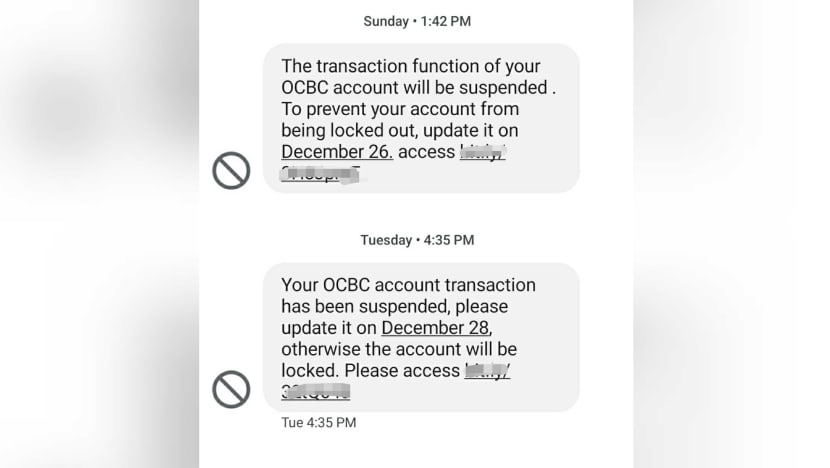

Screengrab of phishing scam messages impersonating OCBC, Dec 2021.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Hardly a day goes by without news of someone being scammed, or a new type of scam popping up. The sheer volume of scam-related news can be overwhelming. We might think, “I've heard it all before” or “It won't happen to me”.

But scams have evolved from the days of poorly written emails offering questionable get-rich opportunities, to highly convincing schemes mirroring the practices of legitimate businesses.

The profits reaped from these deceptive practices have soared into the trillions. Globally, scammers stole about US$1.02 trillion in the past year, according to an October report by non-profit organisation Global Anti-Scam Alliance (GASA) and data service provider ScamAdviser. Singapore holds the unfortunate distinction of having the highest average scam amount per victim, according to the report.

In the first half of this year alone, 22,339 scam cases were reported in Singapore, a 64.5 per cent spike from the first half of last year, with fraudsters siphoning S$334.5 million from victims.

As the frequency of scams continues to rise, an important question arises: Are we, as a society, becoming desensitised to scams? Have we become so accustomed to the unending stream of phishing emails and robocalls that we are in danger of becoming indifferent or less vigilant in recognising and responding to potential threats?

It is important that we do not lose sight of the great hardship caused to the individual victims. For many, the losses could be their life savings or money needed to pay for basic necessities such as food, milk powder, rent or mortgage. The sudden loss of cashflow could be catastrophic for the victims and their families.

EASING THE BURDEN ON VICTIMS

In recent years, the government has stepped up measures to combat scams, including the setting up of the Inter-Ministry Committee on Scams in April 2020 to bring together key government agencies and private sector partners such as The Association of Banks in Singapore to coordinate efforts. Most of these measures, however, have largely been geared towards the prevention of scams.

Last month, the authorities introduced the Proposed Shared Responsibility Framework, which holds negligent financial institutions and telecommunication companies (telcos) responsible for phishing scam losses ahead of victims, if they are found to have breached their responsibilities.

The framework is significant as it represents a first venture into compensatory measures to alleviate the hardship suffered by the individual victims. It also underscores the need for society to provide a collective remedy for individuals.

Developing a loss-sharing framework for scams is far from easy. Some have questioned if such a framework goes far enough to help victims; others have questioned if it might inadvertently lead to consumers letting their guard down.

Given the wide variety of scams, it would be an uphill task to formulate a framework that is simple, equitable and yet comprehensive. The relevant stakeholders may be different in each scam, and the role or responsibility of each stakeholder would again differ on a case-by-case basis. It would also invariably involve subjective - or some may describe as arbitrary - decisions on the allocation of risk, blame and responsibility.

When one takes into consideration the cross-border nature of e-commerce, social media platforms and payment services, the issues become even more acute as jurisdictional issues arise, particularly where there may be different or conflicting frameworks.

For instance, Singapore has encountered difficulties in requesting for the removal of suspected online scam accounts and posts on Telegram, as highlighted by Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam this month.

WHAT MORE CAN BE DONE?

The Shared Responsibility Framework currently covers phishing scams with a digital nexus. This involves a consumer unknowingly revealing his credentials to scammers through a phishing link in Singapore.

Notably, this framework excludes authorised push payment (APP) fraud, where the victim is duped into authorising a fund transfer to a fraudster. It also excludes scams perpetrated through non-digital means (e.g. phone calls or face-to-face) and unauthorised transaction scam variants that do not involve phishing (e.g. hacking, identity theft, malware-enabled variants).

APP fraud has received much attention in other jurisdictions. The UK, for instance, recently enacted legislation mandating banks and payment firms to reimburse APP fraud victims within five days, with the costs shared equally between sending and receiving payment firms.

This model seeks to limit the victim’s responsibility, even if the victim authorised the transfer. Their focus therefore appears to be to alleviate the victim’s financial hardship, and allocate financial risk of the fraud to the payment service provider.

Two exceptions apply: When the customer acted fraudulently or with gross negligence. Save for such exceptions, the UK model places the responsibility on payment firms to protect its customers at the point of payment. The expectation is that payment firms will innovate and develop effective, data-driven interventions to change customer behaviour, and make better decisions on when to intervene and hold or stop a payment.

This approach differs from the Singapore framework, where the victim bears the loss if key stakeholders (banks, payment service providers and telcos) have complied with their anti-scam obligations. These anti-scam duties are largely preventative measures, such as real-time notifications, transactional limitations, and application of anti-scam filters.

It should also be noted that under both frameworks, the potential involvement of other stakeholders, such as social media platforms, e-commerce providers and other online platforms, have not been addressed.

Whilst the statistics show that a significant number of scams occur on these platforms and services, it is often difficult to even identify enforceable jurisdiction over them.

STEP IN RIGHT DIRECTION

Operationally, there are also certain practicalities that need to be considered for a fast and simple claims procedure, given the crucial need to alleviate immediate cashflow concerns for victims.

Under the UK model, victims are expected to be fully reimbursed within five business days. No such timeline has been prescribed under the Singapore framework, although consultation is being sought to determine the required time for the four-stage workflow to be completed.

Further considerations include whether differentiated approaches should be adopted for different types of victims, particularly those identified as a more vulnerable class.

The above illustrates but some of the complexities involved in providing a compensatory framework for fraud victims. There is no easy or unanimous solution, but it represents a step in the right direction towards alleviating the loss suffered by scam victims.

Even with monetary compensation, there remains a number of unresolved issues, including the psychological trauma or stress faced by scam victims, which cannot be discounted.

It is crucial that we do not grow indifferent to the plight of scam victims or desensitised to the pervasive threat scams pose.

Jansen Chow is Co-Head, Fraud, Asset Recovery & Investigations at Rajah & Tann Singapore.