analysis East Asia

China’s Xi proposes GGI to reshape global governance: Will the world follow?

While Chinese President Xi Jinping’s sweeping vision for global governance reform may resonate with states seeking alternatives to a Western-dominated order, questions remain over how far Beijing can go in turning rhetoric into reality.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BEIJING: Chinese President Xi Jinping’s newly unveiled vision for global governance reform signals Beijing’s clearest intent yet to lead in shaping a new world order, analysts say, as the geopolitical landscape reels from intensifying great-power rivalry and fracturing alliances.

The Global Governance Initiative (GGI) calls on countries to work together for a more just and equitable global governance system.

It builds on a string of sweeping international proposals the Chinese supremo has rolled out in recent years, and reflects China’s effort to consolidate them under a cohesive banner, say observers.

Xi has anchored the initiative in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) - the regional bloc where Beijing exerts considerable sway - unveiling it at a recent summit in Tianjin, where he likened today’s geopolitical turbulence to the postwar upheaval that gave rise to the United Nations 80 years ago.

But despite the rhetoric, analysts say questions remain over what China will do in practice under the GGI, and how far it can go in turning its bold vision into reality amid internal challenges and external scepticism over Beijing’s credibility and intent.

“China wants a reordering of the international system and the establishment of a multilateral system where the United States is simply one of many poles,” said Zachary Abuza, an academic focused on Asian geopolitics and security.

“But its drive is fueled as much by domestic weaknesses - from economic slowdown to demographic challenges - as by strength.”

REFERENCING THE PAST TO SHAPE THE PRESENT

Xi formally laid out the GGI at the SCO summit on Sep 1 in a keynote speech to member states, dialogue partners and observers.

He drew a historical parallel to 1945, reminding fellow leaders how the devastation of two world wars had spurred the founding of the UN and opened “a new page in global governance”.

Xi warned that while peace, development and cooperation remain fundamental trends 80 years on, Cold War thinking, hegemonism and protectionism still cast a “lingering shadow” over global affairs.

New threats and challenges are on the rise, he added, pushing the world into what he called “a new period of turbulence and transformation”.

“History tells us that the more difficult the times, the more we must hold fast to the aspiration of peaceful coexistence (and) strengthen our confidence in cooperation and win-win outcomes,” Xi said, framing global governance today as at a crossroads.

“For this reason, I am putting forward a Global Governance Initiative to work with all countries in building a fairer and more reasonable system of global governance, and to jointly advance the building of a community with a shared future for mankind.”

By invoking 1945, Xi was not simply recalling history but framing the present as another moment of systemic change, with China leading the charge as the architect of a new global order, analysts note.

“China is positioning itself as the defender of peace and as the key shaper of the new order it is proposing,” Dylan Loh, assistant professor of public policy and global affairs at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU), told CNA.

Jonathan Ping, an associate professor at Bond University, stressed the ambition behind Xi’s words.

“This juxtaposition is significant - it frames today’s turbulence not as chaos, but as an opportunity for systemic transformation led by China,” he told CNA.

Abuza said Beijing views the present moment as one where shifting global conditions may work in its favour, especially as the US under President Donald Trump roils the international order.

Since reassuming office in January, Trump has steered the US towards a markedly unilateralist agenda - slapping sweeping tariffs on both allies and rivals and withdrawing from key multilateral agreements.

Notably, the US has again withdrawn from the Paris Climate Agreement and moved to exit the World Health Organization, while suspending most foreign aid, including programmes run through USAID, its overseas development agency.

Washington has also announced plans to end funding for European security initiatives such as the Baltic Security Initiative - steps that have deepened concern among North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies and reinforced doubts about America’s long-term reliability in multilateral leadership.

“Xi is trying to equate the post-WWII disorder with the current disorder that he is implicitly blaming on the United States,” Abuza said.

Xi struck a similar note at a grand World War II military parade in Beijing on Sep 3, warning that humanity once again faced a choice between peace and war, dialogue and confrontation, mutual benefit and zero-sum rivalry.

The Chinese leader declared that China remains committed to the path of peaceful development.

“(We) will work hand in hand with people of all countries to build a community with a shared future for mankind,” Xi said.

At the same time, Abuza said that Beijing’s goal is not global hegemony but a system in which Washington is “one pole among many”, as the costs of global leadership and providing collective goods are more than what China wants to pay.

Instead, he said, China is pushing for a multilateral system in which China and rising partners from the developing world check US hegemony.

“From a Chinese point of view, the post-WWII era was established by states like France and the United Kingdom that did not have the power that they claimed to have,” Abuza said.

China has long portrayed itself as a beneficiary of the postwar order, often pointing to its status as a founding member of the UN and a permanent member of its Security Council.

Beijing has repeatedly stressed that it supports the UN’s central role in global governance, even as it calls for reforms to make the system more representative of developing countries.

BUILDING ON PAST MESSAGING

Rather than breaking new ground, analysts say the GGI is a consolidation and refinement of China’s earlier proposals.

Ping from Bond University views it as a strategic rebranding, reinforcing China’s long-term push for a multipolar order rooted in non-Western values.

Since 2021, Xi has introduced the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative and the Global Civilisation Initiative, followed most recently by the GGI.

Broadly, the development initiative champions narrowing global inequality through development, the security initiative stresses fostering security through dialogue rather than military blocs, and the civilisation initiative calls for cultural diversity as an alternative to Western universalism.

Beijing claims that more than 100 countries and international organisations have expressed support for the Global Development Initiative, with varying levels of backing also voiced for the other two.

At the same time, observers say the GGI’s five guiding principles offer a clearer blueprint of what China envisions.

The principles - sovereign equality, respect for international law, multilateralism, putting people first and an action-oriented approach - were laid out by Xi in his Sep 1 speech.

The GGI “offers something akin to a small roadmap” of what a new order might look like, said NTU’s Loh, who added that its value lies in bringing disparate strands of Chinese foreign policy into a more coherent package.

China’s official concept paper on the GGI, released shortly after Xi's Sep 1 speech, makes clear that Beijing is not calling for a wholesale replacement of the current world order, but for reforms that address what it sees as deep imbalances.

It highlights three deficiencies in existing institutions: the underrepresentation of the Global South, erosion of the authority of the UN Charter and its principles, and the lack of effectiveness in tackling global challenges such as climate change, digital divides and new frontiers like artificial intelligence, cyberspace and outer space.

In China’s telling, the GGI is meant to strengthen rather than supplant the UN system, but in a way that tilts representation and rule-making power toward developing countries, noted Abuza.

He believes the initiative could prove more consequential than its predecessors, which “have really gone nowhere” and were often targeted at a domestic audience.

This time, the emphasis on global governance reform may resonate internationally as many in the developing world share calls for change, Abuza added.

“The establishment of a multilateral system and leadership positions for key states in the Global South are a shared priority,” he said, pointing to India’s long-standing demand for UN Security Council reform as an example of overlapping interests.

Taken together, analysts suggest that the GGI is less about novelty than about timing and positioning. By packaging earlier ideas into a clearer framework, Beijing is trying to present itself as a reformer of the international system and a voice for the Global South, they say.

That message found public backing at the SCO summit, with the leaders of Belarus, Pakistan and Iran voicing support for the GGI, according to news reports.

Lao President Thongloun Sisoulith also endorsed the initiative in a bilateral meeting with Xi on the sidelines of the Sep 3 World War II parade, while Malaysia’s Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim signalled support too during his own talks with the Chinese president, according to a Chinese foreign ministry readout.

TURNING RHETORIC INTO REALITY?

What the initiative does not provide, however, is a clear sense of how China intends to move from principle to practice.

While Xi has laid out broad themes such as sovereign equality and multilateralism, he has offered few details on the mechanisms or resources Beijing is prepared to commit, analysts note.

They add that the gap between rhetoric and reality is most evident in how Beijing’s message is received across the Global South - the very audience it is trying hardest to court.

The term broadly refers to developing countries that are poorer, more unequal and have lower life expectancy than their developed counterparts.

Analysts say much of Xi’s language in launching the GGI was directed at developing countries, with repeated emphasis on sovereign equality, adherence to international law and opposition to “double standards”.

They note that the Chinese leader has cast Beijing as a defender of fairness for states that see themselves sidelined in a Western-dominated system.

Ping from Bond University said that while China’s messaging would resonate with countries seeking alternatives to Western-dominated systems, some could also view it as self-serving amid wariness over Beijing’s growing influence.

NTU’s Loh noted the diversity of Global South states, highlighting their varying histories and interests.

“This term is itself contested and open to contestation, (and) the leadership role of China that Xi is projecting will also be met unevenly by countries, even as I think a majority of the Global South are comfortable with China's leadership,” he said.

Perceived contradictions in China’s conduct also risk undermining the credibility of its global governance appeal.

Abuza, the academic focused on Asian geopolitics and security, said it was “rather rich” for the Chinese to call for adherence to international law, pointing to Beijing’s close alignment with Moscow and its defiance of an international tribunal ruling on the South China Sea.

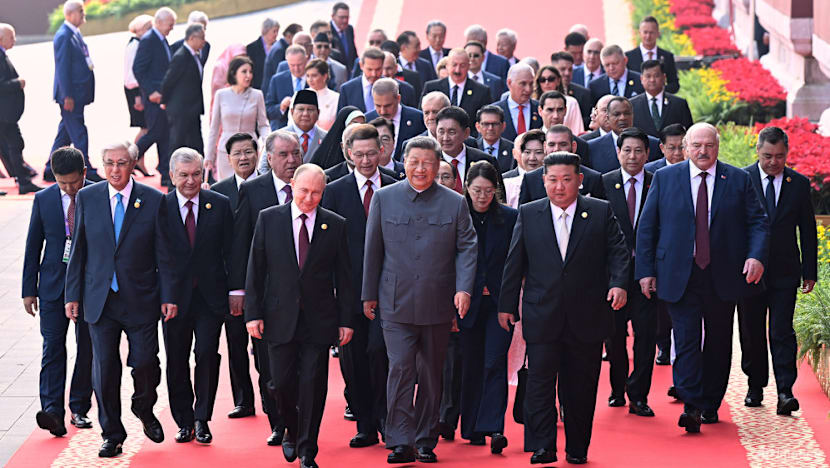

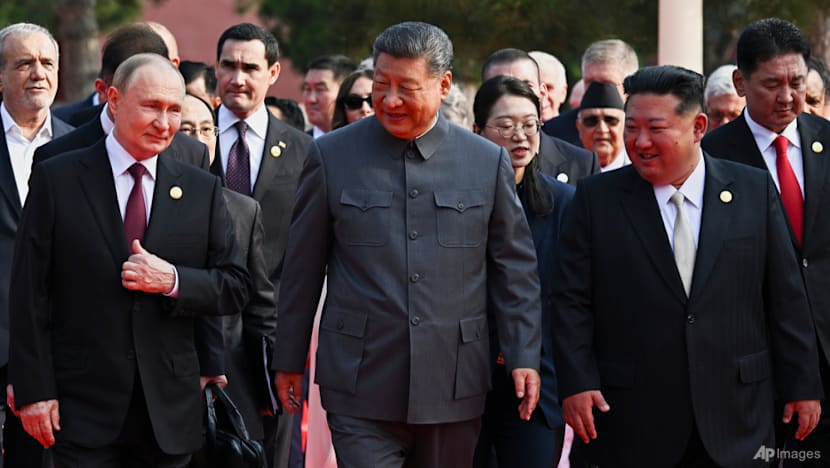

At the Sep 3 military parade in Beijing, Xi shared the stage with Russian President Vladimir Putin, who remains shunned by much of the West over his invasion of Ukraine in 2022. North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, likewise isolated internationally for his nuclear weapons programme, was also in attendance.

Meanwhile, in the South China Sea, China rejects the 2016 ruling under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague that invalidated much of its expansive claims.

This places Beijing at odds with some Southeast Asian states - particularly the Philippines, which has repeatedly accused Chinese vessels of harassment and incursions into its waters. China denies the allegations.

China’s domestic circumstances further complicate its push for a global order it seeks to lead, Abuza added.

“Although Beijing is always trying to project strength, Xi has to cope with enormous economic weaknesses, a decline in domestic consumption, rising capital flight, an enormous demographic challenge, and opaque politics without a clear transition mechanism,” Abuza said.

In his view, these internal strains weigh heavily on Beijing’s approach to the world.

“I think that Chinese foreign policy is driven more by China’s weaknesses than its strengths,” Abuza said.

A PLATFORM OF PROMISE AND LIMITS

Xi’s decision to anchor the GGI in the SCO underscores how Beijing views the bloc as a vehicle for amplifying its message, note analysts.

In his Sep 1 speech unveiling the GGI, the Chinese supremo said the regional bloc had already put forward many new ideas on global governance and should “play a leading role and set an example” in implementing the initiative.

Since its founding in 2001 as a security grouping between China, Russia and Central Asian states, the SCO has expanded to 10 members, including India, Pakistan, Iran and most recently Belarus, along with a wide circle of observers and dialogue partners.

But observers have noted that its growing size has made it more heterogeneous, with overlapping rivalries and diverging interests.

“Beijing is positioning the SCO as a platform to export its governance vision beyond Eurasia … while symbolically powerful, the SCO’s ability to lead global governance reform remains constrained by internal fragmentation and external scepticism,” said Ping from Bond University.

Practical limitations include the SCO’s diverse membership, varying political systems, and limited institutional capacity, he added.

“Some members may resist deeper alignment with China’s model, preferring neutrality or balancing ties with other powers.”

Ultimately, the SCO’s reach is still limited, Abuza said, as it is a Eurasian organisation comprising just 10 members.

Abuza noted that Beijing has long sought to build institutions outside the post-World War II order. As an example, he highlighted the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank that is run in parallel with the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

“Others like BRICS were established and expanded to challenge the international order that’s led by the US and its Western allies, to reflect the economic power of the Global South,” Abuza said.

He said the SCO has followed a similar trajectory, growing from a focus on security to cover economic and cultural cooperation.

“Today, Xi sees it along with the BRICs as a vehicle to lead for a global reordering and the establishment of a multilateral system."